Is the US-China Trade War for Real?

Part 2 of a 3 Part Series on Trump Trade Policy

This incisive article was first published in May 2018 at the outset of the trade war

If Trump’s trade policy toward US allies is ‘phony’, by seeking only token adjustments to trade relations, then the US trade offensive targeting China is for real.

While Trump has repeatedly exempted US allies from tariffs (steel and aluminum), pitched ‘softball’ deals (South Korea), and tweeted repeatedly how well negotiations are going with NAFTA, in stark contrast the actions and words of the US toward China and trade negotiations in progress have been ‘hardball’.

Contrary to media hype, the Trump trade offensive targeting China is not a product of just the past few months. It did not arise in early March with an impulsive tweet by Trump or with his attention-getting declaration to impose tariffs on steel and aluminum producers worldwide.[1] The US trade offensive targeting China was set in motion at least a year ago, in spring 2017. It surfaced last August 2017.

The US Plan to Target China

In August 2017 Trump formally gave the US Office of Trade (OUST) the task of identifying how China was transferring US technology, “undermining US companies’ control over their technology in China”, as well as seeking to do so by acquiring US companies in the US.[2] On August 18, 2017, the OUST laid out in writing four charges in a formal investigation it was undertaking, accusing China of actions designed to “obtain cutting edge in IP (intellectual property) and generate technology transfer”. All four charges were intensely technology transfer related.

That August 2017 scope of investigation document and objectives was then reproduced verbatim on March 22, 2018, with expected recommendations, in the 58 page OUST report of March 22, 2018—not Trump tweets or the steel-aluminum tariffs—publicly launched Trump’s trade offensive against China. [3] The main theme of the report was that China was ‘guilty’ of aggressively seeking technology transfer at the expense of US corporations, both in China and the US.

Based on the OUST report of March 22, 2018, Trump announced plans to impose $50 billion in tariffs on 1300 China general imports, ranging from chemicals to jet parts, industrial equipment, machinery, communication satellites, aircraft parts, medical equipment, trucks, and even helicopters, nuclear equipment, rifles, guns and artillery.. Trump may have appeared in March 2018 to have shifted gears in his trade policy—from a general, worldwide steel-aluminum tariffs focus to a focus targeting China trade— but China has been the planned primary target for at least the past year. Trump just set it in motion publicly on March 23, 2018. A confrontation with China over trade had been planned from the outset.[4]

Trajectory of US-China Trade Negotiations

But an announced plan to impose tariffs at some point in the future is not the same as the implementation of those tariffs. Despite Trump’s March announcement, and declaration of $50 billion in tariffs on China goods imports, a delay of at least 60 days must take place before any further definition or actual implementation of the $50 billion by the US might occur—thus giving ample time for unofficial pre-negotiations to occur between the countries’ trade missions. Technically, the US could even wait for another six months before actually implementing any tariffs. To date there has been only talk and threat of tariffs—on China or on US allies. With China, Trump has merely ‘notched an arrow’ from his trade quiver. The bow hasn’t even been drawn, let alone the arrow let fly.

Following Trump’s threat of $50 billion in tariffs, China immediately sent its main trade negotiator, Liu, to Washington and assumed a cautious, almost conciliatory approach. China responded initially with a modest $3 billion in tariffs on US exports. It also made it clear the $3 billion was in response to US steel and aluminum tariffs, and not Trump’s $50 billion. More action could follow, as it forewarned it was considering additional tariffs of 15% to 25% on US products, especially agricultural, in response to Trump’s $50 billion announcement. China was waiting to see the details. At the same time it signaled it was willing to open China brokerages and insurance companies to western-US 51% ownership (and 100% within three years), and that it would buy more semiconductor chips from the US instead of Korea or Taiwan. It was all a token public response. China was keeping its arrows in its quiver.

Following Trump’s mid-March tariff tantrum, behind the scenes China and US trade representatives continued to negotiate. By the end of March all that had still only occurred was Trump’s announcement of $50 billion of tariffs, without further details, and China’s $3 billion token response to prior US steel-aluminum tariffs. From there, however, events began to deteriorate.

On April 3, 2018, Trump defined the $50 billion of tariffs—25% on a wide range of 1300 of China’s consumer and industrial imports to the US. The arrow was being drawn. The list of tariffed items was the verbatim USTR Report’s ‘list’. Influential business groups in the US, like the Business Roundtable, US Chamber of Commerce, and National Association of Manufacturers immediately criticized the move, calling for the US instead to work with its allies to pressure China to reform—not to use tariffs as the trade reform weapon.

China now responded more aggressively as well, promising an equal tariff response, declaring it was not afraid of a trade war with the US. That was a welcoming invitation for a Trump tweet which followed, as Trump declared he believed the US could not “lose a trade war” with China and maybe it wasn’t such a bad thing to have one. Trump tweeted further that maybe another $100 billion in US tariffs might get China’s attention.

China now notched its own arrow, noting it would raise 15%-25% tariffs on the US and responded to Trump’s $50 billion, identifying their own $50 billion tariffs on 128 US exports targeting US agricultural products and especially US soybeans, but also cars, oil and chemicals, aircraft and industrial productions—the production of which is also heavily concentrated in the Midwest US and thus Trump’s domestic political base.[5]

This particular targeting clearly aggravated Trump, disrupting his plans to mobilize that base for domestic political purposes before the November elections. He angrily tweeted perhaps another $100 billion in China tariffs were called for. In response, China declared it was prepared to announce another $100 billion in tariffs as well, if Trump followed through with his threat of imposing $100 billion more tariffs.

Trump advisors, Larry Kudlow and Mnuchin, tried to clean up Trump’s remarks. Kudlow assured the stock markets, which plummeted with the developments, saying

“These are just first proposals…I doubt that there will be any concrete actions for several months”.[6]

In reply to Trump’s threat of another $100 billion, China Commerce Ministry spokesman, Gao Feng, declared it would not hesitate to put in place ‘detailed countermeasures’ that didn’t ‘exclude any options’. And China Foreign Ministry spokesman, Geng Shuang, added in an official news briefing,

“The United States with one hand wields the threat of sanctions, and at the same time says they are willing to talk. I’m not sure who the United States is putting on this act for”…Under the current circumstances, both sides even more cannot have talks on these issues”. [7]

But all this was still a war of words, not yet a bona fide trade war. To use the metaphor once more: arrows were taken from quivers and bows about to be drawn, but no one was yet prepared to let anything fly.

Through the remainder of April negotiations by second tier trade representatives continued in the background. Meanwhile US capitalists in the Business Roundtable and other prime US corporate organizations added their input to the public commentary process on the Trump tariffs that will continue formally until May 22 at least. Most warned a trade war with China would be economically devastating for their business.

In the first week of May, the Trump trade team of Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, US trade representative, Robert Lighthizer, Trump trade advisor, Peter Navarro and White House director of Trump’s economic council, Larry Kudlow, headed off to Beijing for negotiations. The composition of the US trade team is notable. It reveals deep splits within the US elite, some reflecting Trump interests and others reflecting more traditional elite interests in finance and the Pentagon-War industries. While interests clearly overlapped, the splits reflect differing priorities in the China trade negotiations.

Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin in China for the trade talk (Source: Gulf News)

Treasury Secretary, Steve Mnuchin—the US financial sector and US multinational companies doing business in China; China ‘hardliners’, Robert Lighthizer, the current US trade representative, and Peter Navarro, Trump trade advisor—the interests of the Pentagon and US defense sector; and Larry Kudlow, head of Trump’s Economic Council—likely most concerned with the domestic political impact of the negotiations for Trump.

One of the first reports when the two trade teams first met in Beijing last week was from Mnuchin, who reported the negotiations were going extremely well. Mnuchin of course knew that before he left for Beijing. China had already indicated it was going to approve 51% US corporate ownership of China companies in March; and it further signaled it would approve 100% ownership within three more years. US bankers have always wanted a deeper penetration of China and now they’ll have it. They didn’t even have to give up anything to get it. That doesn’t sound like a ‘trade war’, at least not yet. China was cleverly driving a wedge between the bankers-multinational corporations wanting more access to its markets and the Pentagon-War industries faction of the US trade team that want a stop to technology transfer.

But if one were to believe the US press, the US negotiating team came back from Beijing this past weekend empty-handed and a trade war was imminent. If that were true, there would be no reason for China’s chief negotiator, Liu, coming to Washington for further talks later this week, which was quietly announced after the US trade team returned. US-China trade negotiations are thus continuing, notwithstanding Trump tweets and schizophrenic bombast: One day after the US team’s return demanding China reduce its $337 billion deficit by $200 billion by 2020; another day calling China president, Xi Jinping, his ‘good friend’ and expressing optimism about an eventual trade deal.

US-China trade negotiations will almost certainly take months to conclude, if ever, certainly extending well beyond the November 2018 US midterm elections. This delay will put pressure on Trump to quickly come to some kind of token agreements with NAFTA and other trade partner negotiations also underway. A NAFTA deal is likely within weeks. And it will look more like the South Korea ‘softball’ trade deal negotiated by Trump a few months ago than not.

Early agreements before the end of this summer are necessary for Trump to tout his ‘economic nationalism’ strategy and declare it is succeeding before the November elections. One can also expect more ‘off the wall’ tweets by Trump designed to ‘sound tough’ on China trade and negotiations in progress for the same domestic US political purposes. But they will be more Trump hyperbole and bombast, designed for his domestic political base while his negotiators try to work out the China-US trade changes. Yet it’s unlikely Trump wants a China trade deal before the US November elections. There’s more political traction for him to publicly bash China on trade up to the elections.

What the US Wants from China Trade?

What Trump wants from US allies trade partners are token adjustments to current trade relations that he can then exaggerate and misrepresent to his domestic political base as evidence that his ‘economic nationalism’ theme raised during the 2016 US elections is still being pursued. The US traditional elite will allow him to do that, but won’t permit him to disrupt major US-partner trade relations in general. That’s why NAFTA, and later trade negotiations with Europe, will look more like South Korea’s ‘softball’ deal when concluded.

China, on the other hand, is another question. The issues are more strategic. US elites—both the traditional and the Trump wing—want more from China than they want from other US trade partners. With China, it’s not just a question of ‘token’ changes that Trump might then hype and exaggerate for domestic political purposes.

Currently, the US is pursuing a ‘dual track’ trade offensive: seeking token concessions from allies that won’t upset the basic character of past trade relations but will allow Trump to exaggerate and misrepresent the changes for his domestic political purposes, proving to his base that he’s continuing to pursue his promised ‘economic nationalism’. The key to the first track is ‘token’ adjustments to trade. But, in the second track, what the US elite want from China is a fundamental change in US-China trade relations and those changes aren’t limited to token reductions in the US deficit in goods trade with China.

US-Trump trade objectives in its negotiations with China are threefold: first, to gain access for US multinational companies into China markets, especially for US banks and shadow banks (investment banks, hedge funds, equity firms, etc.), but also for US auto companies, energy companies, and tech companies. Expanding US foreign direct investment into other economies is always a main objective of US trade negotiations everywhere. Despite all the talk about goods trade deficits, for the US trade deals are always more about ensuring US ‘money capital flows’ from the US into other economies, than they are about ‘goods flows’ coming from other countries to the US. Access to markets means first and foremost access for US finance capital.

The US second objective is to obtain some visible concessions from China that reduce that country’s goods exports to the US, without China in turn reducing US agricultural and energy related exports to China.[8]

But the main and most strategic objective of the US is to thwart China’s current rate of technology transfer from US companies in China and from China companies acquiring US companies in the US.

The key technology transfer categories are Artificial Intelligence software and hardware, next generation 5G wireless, and nextgen cyber-security software. The US obfuscates the categories by calling it ‘intellectual property’. But it is the latest technology in these three areas that will spawn not only new industries, and whoever (US or China) is ‘first to market’ will dominate the industries and products for decades to come, but the technologies further represent the key to future military dominance as well as economic.

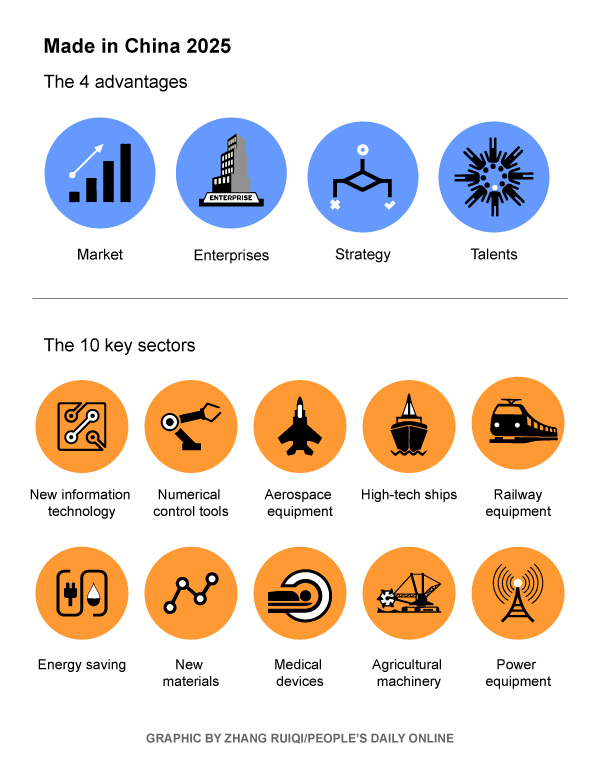

The US is concerned that China may leapfrog into comparable military capability. Already virtually all the new patents being filed in these tech areas are by China and the US. The rest of the world is left far behind. China’s 2017 long term strategy document, ‘China 2025’, clearly lays out its planning for achieving dominance in these technologies over the coming decade. It has succeeded in getting the attention of the US elite, both economic and military.

The US defense sector—i.e. Lighthizer and Navarro—want to stop, or at least dramatically slow, China’s acquisitions of technology related US companies. While tariffs are on paper only so far, the US has been clearly targeting China companies hunting for US acquisitions. Stopping deals with ZTE and Qualcomm corporate acquisitions recently are but the first of more such US actions to come. The US financial-multinational corporation sector want more access to China markets and thus more authority to acquire China companies, whereas the US War Industries-Defense sector wants more limits on China company acquisitions of US corporations.

Trump may want both of these, but even more so he wants some kind of ‘win’ trade deal he can boast to his base about. China will offer a deal conceding on the last two objectives, while holding out on the tech transfer issue.

The contradiction the US faces in negotiations is thus internal. It is that the representatives of the US elite cannot agree on what are the priority changes they want from China. There are at least three US diverging elite interests on the US side, reflecting at least three major objectives sought by the US. That allows China to ‘play off’ one sector of the US elite against the other, giving it a long term advantage in negotiations with the US on trade.

Should the US elite settle for short term concessions from China—allowing for more US financial firms access to China, more US company ownership of Chinese companies, and/or moderate short term gains in China goods exports—but fail to slow China’s technology strategy, then it will represent another ‘defeat’ for the US in relation to China’s growing challenge to US global economic-military dominance. It will represent another success for China, similar in strategic importance to its recent ‘One Belt-One Road’ initiative, its launching of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the adoption of its currency by the IMF for world exchange, and its current development of an Asian common market filling the gap by the US failure to establish its free trade Transpacific Partnership treaty. Technology parity by China with the US may in fact have a greater impact on US dominance than all the above in the long run.

But there’s more to US-China trade than deficits, market access and even technology transfer. There are Trump’s domestic political objectives behind the China-US trade dispute as well. Trump’s political priority has two dimensions: one is to maximize the turnout of the Republican base in the upcoming midterm November 2018 elections. Trump cannot afford to lose either the House or the Senate, or his agenda on immigration, walls, and deportations is finished. Trump also needs to agitate and mobilize his domestic base as a counterweight to traditional US elite resistance when he fires Mueller, the special counsel investigating his pre- and post-election relationships with Russian business Oligarchs.

Thus multiple objectives are contending among and between the different factions behind the US-China trade negotiations: technology transfer for the military hardliners, market access for the bankers and multinational corporations, and Trump getting relatively quick concessions he can sell to his ‘America First’ economic nationalist domestic political base before November. Which is the priority and which secondary. Market access has already been conceded by China, so the alternatives are a trade war over technology transfer or some token adjustments to goods imports to the US that Trump can ‘sell’ to his base. If the latter, China-US trade negotiations outcomes will look more like South Korea and NAFTA. If the US insists on technology transfer, then arrows will be drawn and let fly.

Only then will it become clear that the current US-China trade negotiations are the opening phase in a real trade war, or just another case example of Trump hyperbole for purposes of pandering to his domestic political base.

*

Jack Rasmus is author of the book, ‘Central Bankers at the End of Their Ropes: Monetary Policy and the Coming Depression’, Clarity Press, August 2017. He blogs at jackrasmus.com and his twitter handle is @drjackrasmus. Dr. Rasmus is a frequent contributor to Global Research.