Is Gold a Reasonable Investment?

This essay rounds up arguments for gold as a reasonable investment.

China

Commentators such as Ambrose Evans-Pritchard and Byron King argue that China’s hunger for gold will put a floor on gold prices.

Specifically, they argue that China will “buy the dips” in gold prices, effectively putting a minimum on how low gold prices can go.

Inflation

It is conventional wisdom that gold is a hedge against inflation.

For example, noted inflationist John Williams advises buying gold.

Axel Merk argues that gold is a better buy than TIPS as an inflation bet.

And Taleb advised buying gold in May, since currencies including the dollar and euro face pressures.

Deflation

If gold does well during times of inflation, it makes sense that it would perform poorly during deflationary periods.

But Examiner.com points out that such an assumption is probably untrue.

Specifically, as Examiner.com writes:

Eric Sprott – who manages $4.5 billion in assets, and correctly predicted in March of 2008 a “systemic financial meltdown” – says:

“I believe no matter what environment you’re in – deflation or inflation – people will run to gold,” Sprott said. “Gold is proving exactly what we all would have expected, that in almost any environment, it’s a go-to asset.”

And investment analyst and financial writer Yves Smith argues that gold does well during both periods of deflation and high inflation. She argues:

Historically, gold does well [in] hyperinflation and deflationary [periods]. Gold does poorly under more normal conditions, and gets hammered in disinflationary conditions, a falling but positive rate of inflation.

Analyst Adrian Ash argues that gold’s value actually increases during periods of deflation even if its price drops:

Does the price of gold rise or fall in a deflation?

Hint: It’s a trick question, already tripping up plenty of would-be advisors…

Absent the money-supply limits which the gold standard imposed on the world, people rightly guess that double-digit inflation would prove rocket-fuel for the bull market in gold. Yet the purchasing power of gold nearly doubled during the Great Depression, and it’s risen four-fold during this decade’s low consumer-price inflation as well.

Why? Because both those periods of low price-inflation saw the money-issuing authorities devalue the currency, first with explicit reference to gold but now without daring to name it. Roosevelt in the mid-30s slashed the dollar’s gold content by 40%; the Greenspan/Bernanke Fed devalued the Dollar again to sidestep a DotCom Depression, keeping real interest rates at less than zero, between 2002-2005.

The maestro’s apprentice applied the same trick in the back-half of 2008, but so far to no avail. And now even the European Central Bank is pumping out money – a near half-trillion euros today alone – in a bid to revive bank lending, swamp the currency markets, and pull Germany out of its first flirt with deflation since the 1930s.

Just such a devaluation – and again, absent any stated reference to gold – was attempted by the Bank of Japan a little less than a decade ago.

Indeed, Japan is the only developed nation since the end of the gold standard to have suffered an extended deflation in prices. So far, at least. Germany and Switzerland look set to try for a re-wind, and unless the dollar can outpace the euro’s descent, we might yet see truly sub-zero inflation in the United States, too.

But whatever that should mean for gold prices, all other things being equal, just doesn’t matter. Because the gold price will not get a chance. All other things are not equal, and the policy solution – rank devaluation – can only make gold more appealing to investors and savers, whether the “monetarist experiment” of TARP, quantitative easing or a half-trillion euros proves successful or not.

Japan’s slump into deflation coincided with the Bank of Japan’s “zero interest rate policy” (ZIRP) at the start of this decade. It also saw the gold price worldwide hit rock-bottom and turn higher, a move that analysts (including us) have typically linked to US monetary moves and investment cash looking for safety as the Dotcom Bubble exploded.

But zero-rate money from the world’s second-largest economy shouldn’t be ignored. And today, zero-rate money is all the developed world has to offer – a trick that might not beat deflation, but might just spur a whole new rush into gold.

In other words, Ash argues that you can’t take inflation or deflation in a vacuum. During deflationary periods – like we have now – governments always increase the money supply with a flood of new dollars, which is bullish for gold.

And PhD economist Marc Faber wrote in October 2007 that gold will do well even in a deflation:

How would gold perform in a deflationary global recession? Initially gold could come under some pressure as well but once the realization sinks in how messy deflation would be for over-indebted countries and households, its price would likely soar.

Therefore, under both scenarios – stagflation or deflationary recession – gold, gold equities and other precious metals should continue to perform better than financial assets.

Looking At the Charts

Is Faber right?

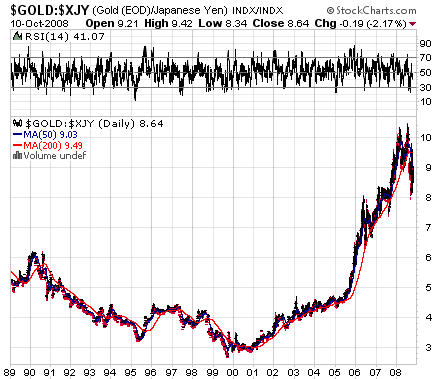

Well, take a look at the following charts showing gold’s performance as compared to the yen during Japan’s “lost decade” of deflation:

Japan’s deflation didn’t definitively end until 2007 or 2008.

This provides some evidence that gold may tend to hold or increase its value at least in the later part of the deflationary period as compared with the relevant national currency.

Moreover – approximately half the time – gold has risen during recessions in the United States:

(The grey vertical bars show periods of recession; the chart gives gold prices in monthly averages; click here for larger image).

If you study the above chart, you will see that gold seems to often fall during the beginning stages of a recession, then rise in the later stages of the recession (before 1971, the dollar was still backed by gold at a fixed price, and so gold did not fluctuate).

But what about Ash’s theory?

The American Enterprises Institute notes:

After five years in a deflationary economic wilderness, the Bank of Japan switched during the spring of 2001 to a policy of quantitative easing–targeting the growth of the money supply instead of nominal interest rates–in order to engineer a rebound in demand growth.

Look again at the first gold chart for Japan, above. Gold appears to start increasing against the Yen in 2001.

This may provide some evidence for Ash’s thesis that it is an expansion of the money supply which pushes the price of gold up in the later stages of deflationary periods.

Uncertainty

Finally, Chris Martenson argues that – in prolonged periods of deflation – we usually see failures of large and significant banks, institutions, and perhaps even states and countries. Because gold traditionally does well during periods of uncertainty, Martenson likes gold during periods of deflation.

Examiner.com notes in a subsequent article:

Merrill Lynch agrees.

Specifically, PhD economist Nouriel Roubini paraphrases a report from Merill Lynch (not available online) as follows:

Short-term rates of 0% are bullish for gold, which serves as a store of value but is a useful hedge against deflation as well, since deflation is inherently destabilizing for financial assets. In the 2001-03 deflationary period, gold rose more than 30%, not to mention the prospect of a return to a dollar bear market. “Gold is inversely correlated to global short-term interest rates and there is a race right now towards 0%. Production is down 4.0% y/y while fiat currencies globally are being created at a double digit rate by the world’s central banks….As for all the talk of a ‘gold bubble,’ it would take a nearly 625% surge in gold to over US$6,000/oz and a flat stock market to actually get the ratio of the two asset classes back to where it was three decades ago when bullion was in an unsustainable bubble phase.”

Gold tends to be less sensitive to global economic slowdown than industrial metals or energy and works better as a hedge against crisis than inflation.

Global Short Term Interest Rates Are Low

The above-quoted Merrill article states:

Gold is inversely correlated to global short-term interest rates and there is a race right now towards 0%.

This argues for gold.

Polls Show Distrust in Government

Time Magazine writes:

Traditionally, gold has been a store of value when citizens do not trust their government politically or economically.

Given the enormous levels of distrust in the government politically and/or economically (and the fact that some have warned of recession-induced violence), gold might do well.

Greenspan and Exeter

Professor Emeritus of Mathematics Antal Fekete has argued for years that gold is the ultimate – and only – safe haven when things really hit the fan.

For example, in 2007 Fekete wrote:

The grand old man of the New York Federal Reserve bank’s gold department, the last Mohican, John Exter explained the devolution of money (not his term) using the model of an inverted pyramid, delicately balanced on its apex at the bottom consisting of pure gold. The pyramid has many other layers of asset classes graded according to safety, from the safest and least prolific at bottom to the least safe and most prolific asset layer, electronic dollar credits on top. (When Exter developed his model, electronic dollars had not yet existed; he talked about FR deposits.) In between you find, in decreasing order of safety, as you pass from the lower to the higher layer: silver, FR notes, T-bills, T-bonds, agency paper, other loans and liabilities denominated in dollars. In times of financial crisis people scramble downwards in the pyramid trying to get to the next and nearest safer and less prolific layer underneath. But down there the pyramid gets narrower. There is not enough of the safer and less prolific kind of assets to accommodate all who want to “devolve”. Devolution is also called “flight to

safety”.

Darryl Schoon makes the same argument.

Here’s a visual depiction Exeter’s inverted pyramid, courtesy of FOFOA:

(Click here for full image)

Alan Greenspan has just lent some support to the theory. Specifically:

Gold prices that jumped above $1,000 an ounce this week are signaling that investors are buying metals to hedge against declines in currencies, former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan said.

The gains are “strictly a monetary phenomenon,” Greenspan said today at an investment conference in New York. Rising prices of precious metals and other commodities are “an indication of a very early stage of an endeavor to move away from paper currencies,” he said…

“What is fascinating is the extent to which gold still holds reign over the financial system as the ultimate source of payment,” Greenspan said.

In other words, Greenspan is saying that investors are moving out of the second-to-lowest step on the pyramid (currencies and government bonds) and into the lowest step (gold).

Greenspan is also verifying what goldbugs like Exeter, Fekete and Schoon have been claiming: that “the barbarous relic” still holds an important place in the modern investor’s psyche.

Are Exeter, Fekete and Schoon right? I don’t know. And Greenspan might be wrong, or trying to excuse weakness in the dollar (as opposed to all paper currencies).

Note 1: Zero Hedge alleges that newly-declassified federal documents prove that gold prices have been manipulated for decades. If these documents are authentic (I have no reason to doubt their authenticity, but have no inside knowledge), if the claims of artificial price suppression are true, if this is widely publicized, if such publicity causes someone like Congressmen Alan Grayson, Brad Sherman, Ron Paul, or Dennis Kucinich to raise a ruckus in Congress, and if Congress as a whole votes to ban such a practice, then the price of gold would presumably rise. That’s a lot of ifs.

Note 2: Some of the best recent arguments I’ve heard against investing in gold are written by Vitaliy Katsenelson. Read this, this, this and this.

Note 3: I am not an investment advisor and this should not be taken as investment advice.