Iran 1953: US Envoy to Baghdad Suggested to Fleeing Shah He Not Acknowledge Foreign Role in Coup

Shah "Agreed," Declassified Cable Says

Document Casts Doubt over Accuracy of US Reports from Tehran — and Adds to Debate over Responsibility for the Coup

On August 16, 1953, the same day the Shah of Iran fled to Baghdad after a failed attempt to oust Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq, the agitated monarch spoke candidly about his unsettling experience to the U.S. ambassador to Iraq. In a highly classified cable to Washington, the ambassador reported: “I found Shah worn from three sleepless nights, puzzled by turn of events, but with no (repeat no) bitterness toward Americans who had urged and planned action. I suggested for his prestige in Iran he never indicate that any foreigner had had a part in recent events. He agreed.”

Despite the passage of more than six decades, fundamental questions persist about Mosaddeq’s overthrow, including who was responsible for this milestone event in Iranian history. The above cable, which was previously published but with these key passages excised for secrecy reasons, is one of several important pieces of evidence pointing to the United States role.

Nevertheless, the question of how important the U.S. and British were in the events of 1953 has recently come under intensified scrutiny. An article in the July/August 2014 issue of Foreign Affairs by noted Iran analyst Ray Takeyh is the latest in a series of analyses by respected scholars who conclude Iranians, not the CIA or British intelligence, were fundamentally responsible.

In the course of explaining “What Really Happened in Iran,” however, the piece spotlights some of the risks of writing about such sensitive historical events, particularly when they involve covert intelligence operations. In particular — how do you know when to trust your sources?

Today’s brief posting is by no means a full assessment or refutation of this argument. (In the interests of disclosure, the author believes the evidence shows that both the CIA — with British help — and Iranians themselves were critical in their own ways to the end result[1]). Instead, the posting mainly points out one of the peculiar challenges confronting historians of 1953, especially on the question of the U.S. and British roles.

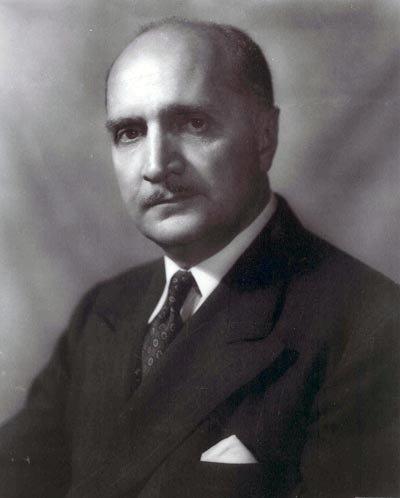

Image: U.S. Ambassador to Tehran Loy W. Henderson (1951-1954). (Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

The challenge is simply that U.S. and British reporting about the coup cannot be taken strictly at face value. The main reason is secrecy. President Eisenhower underscored the need for confidentiality in a diary entry from the time. Dated October 8, 1953, but referring back to August 19, Eisenhower notes:

“Another recent development that we helped bring about was the restoration of the Shah to power in Iran and the elimination of Mossadegh. The things we did were ‘covert.’ If knowledge of them became public, we would not only be embarrassed in that region, but our chances to do anything of like nature in the future would almost totally disappear.” (See Document 1)

Because of that concern, even internal U.S. records (not just those aimed at public audiences, such as Kermit Roosevelt’s memoir, Countercoup) sometimes cast events in a particular light, exaggerated them, or omitted key facts for the sake of protecting the operation.

A case in point is U.S. Ambassador Loy Henderson’s August 20 preliminary report to the State Department on the events surrounding the coup (Document 2), which the Foreign Affairs article cites. Henderson, initially opposed to the coup plan, was eventually read into the program in detail. Yet, he makes no mention whatsoever of the various CIA-planned activities, either in terms of their effectiveness or the lack thereof. Instead, he writes as if there had been no such activities at all.

Why? Because very few officials knew about the plans, including in the State Department, certain quarters of which were still innocently proposing approaches to Mosaddeq after the operation had been put into play. Henderson was not about to jeopardize operational security by divulging secrets in a reporting cable he knew would attract wide attention within the Department. Therefore, even if his expression of surprise at the size of the crowds on August 19 was genuine — and there is reason to believe it was overstated (see Document 2 description below) — it cannot be assumed he was telling the full story as he knew it, much less that he believed the covert operation had been immaterial.

Henderson’s follow-up cable (Document 3) to the Department the next day, August 21, makes this point even more starkly. In it, he coyly reports that “Unfortunately impression becoming rather widespread that in some way or other this Embassy or at least US Government has contributed with funds and technical assistance to overthrow Mosadeq and establish Zahedi Government.” Since he knew all about the plans, this could only have been a deliberate attempt to protect the operation from wider disclosure.

The British engaged in the same Orwellian exercise. An example is the British Foreign Office report to the Cabinet shortly after the coup (Document 4). It also makes no mention of the joint clandestine operation, the success or failure of which would have been of high interest to anyone with access to it.

Image: Ann K.S. Lambton, noted British Iran specialist and advocate of Mosaddeq’s ouster. (Photographer unknown)

For a better idea of how some British Iran watchers thought London should act during this period, see Document 5 from two years before the coup. In a conversation with a Foreign Office colleague, the venerable Ann Lambton brusquely spells out her preferences for how to deal with Mosaddeq — i.e. to “under-mine” him using “covert means” in order to “create the sort of climate in Tehran which is necessary to change the regime.”

The desire to keep information about the operation hidden has continued long after the fact. It is worth recalling that the single most important compilation of U.S. records about the overthrow — Foreign Relations of the United States, Volume X, “Iran,” 1951-1954 — became a symbol of historical manipulation when it was published in 1989 without a single reference to the American or British parts in the operation. (The State Department Historian’s Office expects to produce a “retrospective” volume in Summer 2014, which reportedly will contain CIA and other previously withheld documents that will shed new light on American thinking and activities during the coup period.)

The final document in this posting (Document 6) is an August 17, 1953, cable from the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad reporting on the ambassador’s meeting with the Shah who had just fled Iran that day. Although it deals with events prior to the second coup attempt (which is the focal point for those arguing the case for Iranian responsibility), the cable makes it clear the Shah was fully aware of the importance of the U.S. in recent events (see description below). The document first appeared in the FRUS volume above, but the key portions mentioned here were excised. The unexpurgated document, obtained from files at the National Archives and Records Administration, is presented in this posting.

These examples do not presume to deal with all the arguments made in Foreign Affairs or elsewhere by others with a similar take on the subject. They also certainly do not represent every instance of questionable sourcing that exists on the overthrow. But the documents below do point up a major wrinkle that anyone interested in the 1953 coup must take into account.

The Documents

Document 1: Dwight Eisenhower, Diary entry, October 8, 1953, Secret

Source: Eisenhower Library

The section of this diary entry dealing with Iran sums up President Eisenhower’s understanding of events at the time. In a Weekly Standard piece in 2013 that closely parallels his Foreign Affairs article, Ray Takeyh implies that Eisenhower did not believe Kermit Roosevelt’s account, quoting the diary as saying the CIA agent’s report “seemed more like a dime novel than an historical fact.” However, the full passage makes clear the president accepted Roosevelt’s version without reservation, commenting on “exactly how courageous our agent was in staying right on the job [after the first attempt] and continuing to work until he reversed the entire situation.”

Document 2: Loy Henderson, Cable #416 to the State Department, August 20, 1953, noon. Confidential

Source: FRUS

This preliminary report on the events of recent days is suspect as a full and accurate record since it avoids any reference to U.S. involvement, even though that fact was well known to Henderson and others at the Embassy. That makes it more difficult to assess the rest of the detailed rundown of events it provides. The summary may well reflect the true beliefs or best information available to the Embassy, but without any sense of the sources used there is reason to be guarded. For one thing, the situation was by most accounts still highly fluid. Even the Americans and British were worried that the Tudeh might mount a serious counter-attack, and showed frustration that Zahedi had not been more effective in forestalling that possibility. Furthermore, it was entirely in line with the goals of the covert operation (regardless of one’s views about its efficacy) to present the events of 28 Mordad in as positive a light as possible, including portraying it as entirely spontaneous and far-reaching.

In that regard, a lingering question requiring further clarification — even after all these years — is what the true size of the crowds was. The scholar Ali Rahnema in a forthcoming book gives a detailed breakdown of the demonstrations on August 19.[2] Among other sources, he notes that even the pro-Zahedi press (Dad) came up with a crowd figure of 7,000. If accurate, that hardly compares to the numbers given for various Tudeh marches (e.g., in July 1952 and 1953), and would not by itself justify characterizing 28 Mordad as a major revolt.

Document 3: Loy Henderson, Cable #436 to the State Department, August 21, 1953, 2:00 p.m. Secret

Source: FRUS

Beyond the opening passage quoted above, this cable is interesting for the arguments it advances in the second paragraph in favor of keeping mum about the question of foreign involvement in the overthrow — even to the point of declining to deny the charge. Prophetically, the author notes that the current government, “like all governments of Iran eventually will become unpopular and at that time US might be blamed for its existence.”

Document 4: Foreign Office, Brief for the Cabinet, “Persia,” August 25, 1953. Secret

Source: British National Archives

It is hard to know whether the author(s) of this briefing knew about the joint U.S.-British operation. Clearly, the Cabinet was meant to be kept in the dark about it. Much of the analysis in the memo sounds perfectly reasonable in retrospect — a fact that does not at all imply that those in the loop believed their role had been insignificant.

Document 5: E. A. Berthoud, Minute, “Persia,” June 15, 1951. Confidential

Source: British National Archives

Ann K.S. (Nancy) Lambton was a renowned scholar of Persian history and culture, well-connected with the British government, and regularly consulted on Iranian politics, especially during the Mosaddeq period. She reportedly had as little respect for the Shah as she did for the prime minister, whom she bluntly advocated overthrowing. Lambton proposes sending a colleague, Robin Zaehner, to Iran to put in place the pieces she sees as necessary to removing Mosaddeq. (Foreign Secretary Herbert Morrison did in fact assign Zaehner to help put together a coup plan.) Lambton’s comment that Zaehner “was apparently extremely successful” at advancing British interests through propaganda during the 1945-46 Azerbaijan crisis says a great deal about British assumptions about their power to influence events in Iran.

Document 6: U.S. Embassy Baghdad, Cable #92 to the Under Secretary, August 17, 1953. Top Secret / No Distribution

Source: National Archives and Records Administration

This cable from U.S. Ambassador Burton Y. Berry in Baghdad was classified Top Secret and directed personally to the Under Secretary of State. Given its audience of one, the author feels freer than Henderson evidently did in the above reports to be forthright about such sensitive topics as the Shah’s state of mind and his admissions concerning the U.S. role in the coup to that point. Interestingly, the Shah made several statements to Berry that showed his dependence on the guidance of a person he refers to only as “an American.” The cable notes this was “not (repeat not) an official of the State Department,” leading to this author’s conclusion it was probably Kermit Roosevelt. The ambassador also makes clear the Shah intends to continue to get “advice from his American friend” before taking any further steps — a small indication that calls into further question the idea that the U.S. role can be entirely dismissed even after the initial failure of the CIA-British plan.

For more information contact: Malcolm Byrne 202/994-7043 or [email protected]

Notes

[1] For a comprehensive statement of this view, see the Conclusion of Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 Coup in Iran, edited by Mark J. Gasiorowski and Malcolm Byrne (Syracuse, 2004). See also the various previous postings linked at the top of this page.

[2] Ali Rahnema, Behind the 1953 Coup in Iran: Thugs, Turn-Coats, Soldiers, Spies (Cambridge University Press: November 2014).