Interview: ‘Ask the Wrong People About Drone Deaths and You Can be Killed’

Reporting from the border of North and South Waziristan for Channel 4 News – but with restrictions. Local journalists often fare better. (Photo: TBIJ)

The US has so far killed more than 2,500 people in its ‘secret’ drone war in Pakistan. All but 22 of 372 recorded CIA strikes have taken place in Waziristan – a hostile and inaccessible area for journalists and researchers.

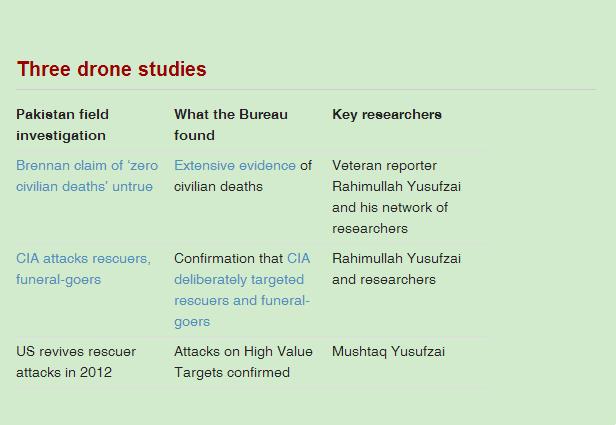

In the past two years the Bureau has published three major investigations into CIA strikes in Pakistan – all based on field research in Waziristan. So how has it been able to achieve this?

The inability of western reporters to access parts of Waziristan is certainly overstated. I was able to visit parts of South Waziristan with the Pakistan military recently for Britain’s Channel 4 News(pictured above), and to speak first-hand with some of those villagers directly affected by CIA drone strikes. Other international media visiting recently have included France 24 and NBC News.

Related article – Bureau investigation finds fresh evidence of CIA drone strikes on rescuers

That said, journalists do face major restrictions from both the state, which limits access to the tribal regions, and the militant groups who control much of the region. Only certain areas can safely be accessed – most of North Waziristan remains off-limits, for example. And Pakistan’s military and intelligence officials often seek to influence reporters – just as their western counterparts sometimes do.

The solution for many western news agencies – and the Bureau – is at times to seek the assistance of skilled local reporters who are able to visit the tribal areas away from the spotlight.

One such man is Mushtaq Yusufzai (above), who carried out the Bureau’s present study into the revival of deliberate CIA attacks on rescuers in 2012. A respected journalist, his work frequently appears in NBC News reports, and he is also a regular reporter for The News, an English-language Pakistan paper which covers the covert drone war.

He is one of the few people able to report authoritatively on events in Waziristan, thanks to extensive contacts with government and military officials, with militant groups and with tribesmen. Those links have been built up over many years – but are not without risk.

I met Yusufzai in Islamabad to discuss the challenges of reporting from the tribal areas.

‘After 9/11, I’ve worked in each and every tribal region. It is very, very important that you’re able to go there and speak to locals, learn their customs and traditions,’ Yusufzai tells me.

‘I was lucky – thanks to my uncle Rahimullah Yusufzai’s reputation [a veteran BBC World Service reporter] anywhere I went, people respected me,’ he says. ‘People invited me into their own homes and guest houses. And they helped me, taking me to all parts of Waziristan… So I developed very good contacts among the local people, officials and among the Taliban, or those who would later become the Taliban.’

Related story – Get the Data: The return of double-tap drone strikes

Journalists operating in the region must juggle these often conflicting relationships. ’If you’re professional and have no hidden agenda, no personal agenda, I think there’s no problem. People can trust you. People can share with you sometimes even very sensitive information. If you remember in 2010, the Pakistani government was saying that Hakimullah Mehsud [leader of the Pakistan Taliban] was killed in a drone attack. Everybody was saying that, except me.’

Yusufzai’s TTP sources turned out to be correct – and to this day Hakimullah Mehsud continues to launch terrorist attacks on Pakistan’s population.

Some analysts claim that reporting from the tribal areas is often unreliable. Yusufzai is inclined to agree: ’There is some truth to it. Reporting can be very, very poor and if you rely on your local stringers and journalists they may never ever tell you the truth, because they’re rarely paid, they don’t want to risk upsetting people. The Taliban or security officials or local people might blame him for doing his job. So sometimes it’s easier for him to say nothing – or the wrong thing,’ he says.

Despite the risks, the militant groups can be an important source of information: ’There are a number of people who know, among the Taliban’s leadership, among the fighters, what’s actually happening. So I tell them that I want to write a story about these things if they can help. To some extent they will allow you, but if it’s related to their senior people, to the commanders, they may not allow you to do it and tell you instead to use their public statements.’

State sources such as the military and Pakistan’s powerful intelligence service, the ISI, can be less well-informed. ’Often they don’t themselves have access to those areas,’ says Yusufzai.

Journalists are at risk of interference from the army and ISI. Yusufzai assumes that his phone is often listened to, which he believes can put journalists in danger. ’Sometimes it becomes very dangerous, and the Taliban suspect it is possible you are working for spy agencies, for the government.’

There is certainly risk for Pakistan’s many reporters. The country has featured in the top five most dangerous nations on earth for journalists in every year since 2005, with 44 reporters killed. Some died trying to report on US drone strikes.

Rescuer strikes

The Bureau recently engaged Yusufzai to examine reports of a series of strikes in 2012 that were reported to target rescuers from earlier drone attacks. He was chosen because of his reputation for independence. He examined half a dozen strikes, and what he found sometimes differed significantly from contemporaneous media reports.

‘When I was working on this project, I talked to my Taliban sources and I said, “Every time it is reported that four or five were killed in each and every drone strike. But we also know that sometimes, they kill innocent people, and especially those who come to rescue. And we have observed this, that most people are killed in the second attack. So help me to understand who died.”‘

He approached other sources too – though he often had to tread carefully: ’I spoke to those tribesmen who have close links with, who might be supporting the Arabs and Punjabi Taliban. And then I spoke to security people who are dealing with ISI and other agencies.’

One major difference between the 2012 strikes on rescuers and those examined by the Bureau during the period 2009-2011 was an absence of reported civilian deaths. In Yusufzai’s view, villagers have learned to fear returning CIA drones.

‘Villagers and civilians, local people, they don’t want to go to any site [of a recent drone attack]. Firstly they are not allowed by the Taliban. Especially when there are foreigners staying in a house or a car. Nobody is allowed to go there and see them. And then they are afraid of the drone strike, they think they will fire more missiles… So that’s why nobody wants to go in to be killed. So most of the times we don’t say they’re civilians, we don’t know for sure. But the civilians do not go there.’

Yusufzai found no firm evidence of civilian deaths, but he is keeping an open mind. An attack on July 6 2012 killed three brothers from the same village, for example – and Yusufzai remains unsure of their status. In a parallel independent investigation, legal charity Reprieve reports eight civilian rescuers died in the same attack.

‘It is possible some civilians were killed, but we don’t know,’ says Yusufzai. ‘I tried my level best to know the names [of those killed]. But it’s extremely hard. The exception was these three brothers. But in most cases we don’t have exact information about civilian casualties.’

The biggest challenge is convincing the Taliban to release the names of militants killed by the CIA.

‘Most of the time, those who are killed belong to some other places and people don’t know their names. And they’re not able to ask who was killed. And media people are suspected [of being] spies. If you [are] working for the media and you ask someone about who was killed, then you are no more,’ he tells me.

‘So you do it very carefully. You don’t ask this directly of the Taliban, you… have to ask carefully from those who are collaborating [with] them, who have some relation with them. And certainly not at that time, it needs to be after some time.’

‘I often ask the Taliban, “Why don’t you release their names, why do you hide the number of people who were killed? Why don’t you allow us to go in and get videos?” And they say, “Look, the Americans, they are the enemy. If we allow you to come and get pictures, you’ll show those pictures to the Americans. And they will say, “Oh, so we killed these people, they are enemies.” So they will be happy. We don’t want to make them happy”.

The Bureau will be building on its already extensive experience of field investigations in Pakistan later this year, when it launches the Naming The Dead project.

‘We’ve set ourselves a tough challenge – identifying hundreds more of those killed by the CIA in Pakistan, be they militants or civilians,’ says project leader Rachel Oldroyd.

‘Vital to our success will be the knowledge and insight of an extensive network of journalists and researchers like Mushtaq Yusufzai, They often risk a great deal to ensure we understand what is happening, something we appreciate greatly.’

Follow Chris Woods on Twitter.

Sign up for email alerts from the Bureau here.