International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia: The 20th Anniversary of an Illegal Court

Twenty years ago, on 25 May 1993, the UN Security Council created the so-called International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). (1) The UN Charter does not give either the Security Council or any other UN body the right to create international law courts, which means that the creation of the tribunal was unlawful. Those who established the ICTY were fully aware that they were acting unlawfully, but went ahead nevertheless.

It is often said: what is the use of discussing the legality of the tribunal now? Even if it was established in violation of international law, it served a «good cause». Really?

Officially, the ICTY was established to punish those responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law during the armed conflict in former Yugoslavia. However, the outcome of twenty years of this court’s activities has been the destruction of the top political and military leadership of just one of the countries involved in the Yugoslavian conflict – the country that was the target of the aggression. The countries that started the war in Yugoslavia, meanwhile, received full and even pointedly triumphant vindication! There is good reason why those who established the tribunal, having included war crimes in the tribunal’s jurisdiction, «forgot» to also include crimes against peace. Otherwise the tribunal would have found it difficult to argue why it was prosecuting the victims of the war and acquitting those that had unleashed it.

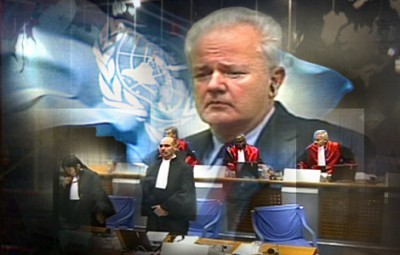

From the outset of the ICTY, its activities were illegal… The Tribunal’s first order was the arrest of General Djordje Djukic, who was ill with cancer. They tried to wear him down, taking advantage of his seriously ill condition and the General died five months after his arrest. Hereafter, the list of the ICTY’s Serbian victims has grown continuously. Simo Drljaca was killed during the course of his arrest. Milan Kovacević died in the ICTY’s Detention Unit, having not received medical help. Slavko Dokmanović was killed in the ICTY’s Detention Unit (the official version of «suicide» does not stand up to scrutiny: there is every reason to classify his death as «murder»). Dragan Gagović was killed during the course of his arrest. Novica Janjić committed suicide trying to prevent his extradition to The Hague (it later turned out that the prosecution retracted the charge). Vlajko Stojiljković (Serbia’s former Minister of Internal Affairs) committed suicide trying to prevent his extradition to The Hague. Momir Talić died in the ICTY’s Detention Unit. Milan Babić (the former President of the Republic of Serbian Krajina) was killed in the ICTY’s Detention Unit (the official version of «suicide» does not stand up to scrutiny: there is every reason to classify his death as «murder»). Slobodan Milošević was killed in the ICTY’s Detention Unit (the official version of «death from natural causes» does not stand up to scrutiny: there is every reason to classify his death as «murder»). There is no other tribunal that is able to boast of such «achievements». In addition, only Serbians have died at the ICTY.

We will now look at the unlawfulness of the ICTY’s establishment in greater detail. On the day of this institution’s ignominious anniversary, it should once again be remembered that it exists outside of international law and its verdicts are illegitimate.

Firstly, the resolution on the creation of the ICTY makes no reference to any article of the UN Charter. The Security Council did not take advantage of the reference to Article 29 of the UN Charter provided by the UN Secretary General, since it was clearly inappropriate. (2) However, the UN Secretary General openly acknowledged at the beginning that the proper way to create an international tribunal was through the conclusion of an international agreement, but then declared that the creation of an international tribunal through the adoption of a Security Council resolution was also acceptable, since according to the Secretary General, the conclusion of an agreement would «take too long» (this argument is clearly unconvincing from the point of view of international law). Absolutely everybody knew that the only legitimate way to create an international tribunal was through the signing of an international agreement. The initial draft of the ICTY Statute was in fact prepared as the draft of an international agreement, and before this the draft of the ICTY Statute had been developed within the framework of the OSCE also in the form of a convention.

Secondly, certain member states of the Security Council (China and Brazil, for instance) immediately declared that there was no legal basis for the creation of an international criminal tribunal by the Security Council.

Thirdly, the Hague Tribunal itself tried to find legal justification, but was unable! Many believe that the ICTY has gathered together the world’s best judges. What nonsense! Many of them have never been judges in their lives before! Even the lawyers there are not the very highest ranking. For example, the court failed to justify what would seem to be an issue of vital importance to the court itself – the lawfulness of the ICTY’s creation. The matter was initially examined by the Trial Chamber. (3) The Tribunal examined the question of its own lawfulness independently and violated one of its own general principles of law Nemo iudex in sua causa («No man should be judge in his own case»). The Trial Chamber dismissed the case on the basis that the ICTY does not have the jurisdiction to examine the lawfulness of UN Security Council resolutions. However, in coming to this decision, the Trial Chamber stopped half way. If the Tribunal was unable, then who was? The answer is obvious: the UN has a principal judicial organ – the International Court of Justice of the UN. It is interesting that the former President of the International Court Gilbert Guillaume (France) observed that it would have been «difficult to imagine that the tribunal would have given a negative answer [regarding its lawfulness], effectively signing its own death sentence». Guillaume also noted that the most correct decision regarding the lawfulness of the ICTY’s creation would have been a request for the legal opinion of the International Court as the UN’s principal judicial organ as well as a body independent of the tribunal itself. However, this was obviously not done by the Trial Chamber.

The Appeals Chamber also came to a decision. It revoked the decision of the Trial Chamber and decided that it had the jurisdiction to look into the issue of the ICTY’s legality. The court rejected the argument that an international tribunal could only be established by international agreement, citing the Administrative Tribunal established by the UN General Assembly as an example. According to the judges, this meant that the Security Council, «having even more authority», could establish judicial bodies. However, this argument is unconvincing. Firstly, it is not about the General Assembly but the Security Council, where not all UN member states are represented, as with the General Assembly, but just fifteen. Secondly, the Administrative Tribunal is exclusively an internal organ of the UN and only has jurisdiction with respect to employees of this organisation. Thirdly, the jurisdiction of the Administrative Tribunal of the UN does not apply to criminal matters. Nobody is disputing the right of an international organisation to create internal organs for the regulation of legal matters concerning its employees; what is being disputed is the right of an international organisation to make decisions that fall outside the scope of its authority. According to Article 2 of the UN Charter, an organisation cannot interfere in the domestic jurisdiction of states: «Nothing contained in the present Charter shall authorise the United Nations to intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any member states».

The creation of the ICTY violated the principles of national sovereignty – a fundamental principle of international law and, most notably, the UN itself. The Security Council created an organ and gave it jurisdiction that it did not possess itself: to try individuals – citizens of UN member states. Another argument by the Appeal Chamber of the ICTY was in reference to Article 41 of the UN Charter, which lists the measures the UN Security Council can take in cases of breach of the peace. The Chamber dismissed the defence’s argument that the article makes no mention of the creation of judicial organs on the grounds that «the measures listed are only examples». It is impossible to recognise such an explanation as satisfactory. The judges ignored the defence’s main argument – that the UN Security Council does not have judicial powers. The judicial organ of the UN is the International Court of Justice, but even that has moved beyond the scope of the UN Charter. It should be noted, however, that the Statute of the International Court of Justice is an integral part of the UN Charter, the formal distinction of these two international agreements providing non-UN member states with the opportunity to be a party to the Statute of the International Court of Justice and UN member states the opportunity to occupy a special position within the Court. This once again underlines the fact that as an executive body, the UN Security Council does not have any judicial powers. The International Court of Justice acts in compliance with a separate international agreement – the Statute of the International Court of Law. With the establishment of the ICTY and the ICTR (the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda), the UN Security Council gave these institutions judicial powers which it did not possess itself, thereby violating yet another general principle of law Nemo in alium potest transferre plus juris quam ipse habet («No one can transfer a greater right to another than he himself has»).

In other words, neither those who established the tribunal, nor the tribunal itself, has so far been able to find any legal basis to support the legality of creating the ICTY.

It is impossible to lightly brush aside the fact that the court has been established illegally. Established illegally, the Hague Tribunal cannot become a judicial body since it was created for purposes other than those officially stated. Twenty years’ development of international criminal justice has demonstrated this quite convincingly. Today, an international mechanism is being created for the destruction of progressive international law and the creation of a new and repressive international law. The ICTY adopted a series of resolutions which violate the regulations of international conventions currently in force and the rules of customary international law. This is no accident. A single judge would not take on that kind of responsibility. Here they make such decisions collectively, which gives clear evidence of the task before them. One of the ICTY’s main «services», and one which has also maintained its system of international «justice», is the removal of immunity for heads of state and governments. It is obvious that this objective was not decided by the judges on their own initiative.

In 2003, a UN Security Council Resolution was adopted ordering that the ICTY complete the examination of all cases by 2010. However, the Tribunal has not implemented this resolution. In fact, the president of the ICTY announced that the Tribunal refused to implement the resolution «until Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić had been caught». The Tribunal has not yet come to a close.

The battle with the Hague Tribunal has led to a paradoxical result: another tribunal has now been established alongside the International Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia which is allegedly to become the ICTY’s successor. From 1 July 2013, the ICTY will hand over its authority to the so-called «Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals». However, it will not be handing over all of its powers, only its authority on new appeals. All of the judicial proceedings already under way at the ICTY will continue. So instead of one tribunal, there is now going to be two in operation. Incidentally, both are headed by the American Theodor Meron, while the secretary of both is the Australian John Hocking. The chief judges of both are also the same (although to these have been added judges from Burkina Faso, Uganda and Kenya). Now nobody knows when the ICTY will be closed. The ICTY says it will be when the examination of all its cases come to an end.

While marking twenty years since the creation of the ICTY, there is one more fact that should be remembered. The UN Security Council resolution on the creation of the ICTY was adopted in 1993 based on a draft sponsored by the Russian Federation, among others. That was obviously a different Russia, and today Russia’s foreign policy has radically changed its attitude towards this court of law. In an acutely critical assessment of twenty ignominious years of the ICTY, today’s Russia will find additional reasons to actively oppose both the massacre of Serbian patriots who dared to challenge NATO’s hegemony and any attempts to violate international law.

Notes