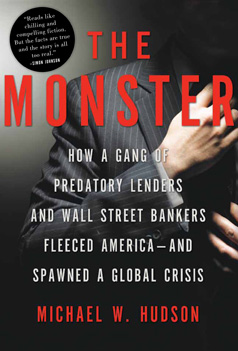

Inside the Mortgage Monster

Book Excerpt

(Image: Times Books)

Back in the days of the home-loan boom, loan officers at Ameriquest Mortgage worked hard and played hard. They put in ten- and twelve-hour days punctuated by “Power Hours”—frenzied telemarketing sessions aimed at sniffing out borrowers and separating the real salesmen from the washouts. A frat-house mentality ruled, with liquor and cocaine flowing freely. “It was like college, but with lots of money and power,” one former Ameriquester, Travis Paules, recalls. In this excerpt from his new book, The Monster: How a Gang of Predatory Lenders and Wall Street Bankers Fleeced America--and Spawned a Global Crisis, investigative reporter Michael W. Hudson tells the story of Travis Paules’ first year and a half inside America’s biggest—and most predatory—subprime mortgage empire.

As more borrowers signed loans and more dollars flowed in from Wall Street, Ameriquest began hiring new salespeople and opening new branches around the nation. Travis Paules was one of the company’s hires in 1998. The company recruited him away from his job at a consumer finance company and put him in charge of opening an Ameriquest outpost in Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Harrisburg.

Paules was twenty-eight. He had been working for three years in nearby Lancaster for American General Finance. He wasn’t, he later recalled, an upstanding guy. He smoked pot every day, boozed, gambled, frequented strip clubs when he had a little extra cash. One thing he did have going for him was a work ethic. His mother had been a disciplinarian. She’d hated laziness. When he was thirteen, his father had given him a copy of Napoleon Hill’s Think and Grow Rich, the bestselling guide to striving and success. At American General, he was a “company man,” a by-the-book branch manager, always on time and diligent with his paperwork. He cut no corners because American General made it clear that it didn’t want him to cut corners, and that he should balance the need for loan production with the need to make sure borrowers could really repay their loans. “I played within the sandbox they allotted me,” he said. “I always liked to say: My personal morals aren’t good, but I have good business morals.”

He was earning just under $50,000 a year. An acquaintance who worked at Ameriquest suggested he could make a lot more at the up-and-coming mortgage lender. As much as $150,000 a year running a branch. Soon after, Paules’s supervisor at American General told him that he’d have to wait on the promotion he had been expecting, and that he shouldn’t expect more than a 3 percent raise for the year. Paules picked up the phone and dialed Ameriquest.

About the only guidance he received before he opened the Camp Hill branch came from his new supervisor. She suggested he bring a list of American General employees and borrowers with him. He could draw from the employee list as he recruited for the new branch and hit up American General’s customers with offers to refinance their debts. Paules thought that sounded strange. It wasn’t the way he’d been taught to operate at American General. He quickly learned, though, that Ameriquest was a different company from the one he had worked at before.

Soon after he started, he traveled to Las Vegas for an Ameriquest managers’ conference. The lender had booked rooms at the MGM Grand, the world’s largest hotel-casino complex, replete with nightclubs, waterfalls, and theme-park rides. Here was a company, he mused, that knew how to reward and motivate its employees. There were free drinks and a “money booth” that offered exuberant branch managers the chance to jump in and grab as many wind-churned bills as they could stuff in their pockets. The training sessions seemed to be an afterthought.

Before Paules left Vegas, a senior executive suggested that he and Paules make a “side bet.” It was a ritual at Ameriquest. Bosses spurred underlings to greater production by betting on what their numbers would be over a specific time period. If Paules could get his branch to hit at least $1.5 million in its first full month of operation, the company would multiply the standard commissions for Paules and his employees by a factor of 1.5.

Back home in Pennsylvania, he leaned heavily on his list of American General customers. The branch recruited more than a dozen customers away from his previous employer and by the end of the month it had booked twenty-one loans in all, a company record for a new branch. Those twenty-one mortgage contracts translated into $1.6 million in loan volume.

Paules had won his bet and made a lot of money for himself and his staff. He swaggered a bit as the new month began. But he quickly learned that last month was old history. At Ameriquest, you were only as good as your current month. The branch had exhausted the leads from his pool of American General borrower. As the new month came to an end, the office’s numbers had dropped dramatically. While fellow branch managers listened in on a conference call, a supervisor chewed him out, counting off a roll call of epithets that described his performance: “one-month wonder,” “king for a day,” “shitting the bed.”

Paules regrouped, aiming to prove he was a top producer. If he’d done everything by the book at American General, it was because that’s what had been required of him. At Ameriquest, he followed cues that let him know that he needed to be creative about booking loans and making money. It wasn’t a case of an innocent being corrupted. It was a case, he said, of an unprincipled personality finding a place that encouraged his self-serving instincts. “It’s hard to have a guilty conscience if you don’t have a conscience,” he said. “Anything that benefited production—that benefited me and benefited my wallet—I’d do it.”

About the only check on his behavior was the risk of getting caught. At Ameriquest, the risk was low, if you covered your tracks and didn’t get too out of control. He let his workers fiddle with about 10 percent of the loan files, only the deals where falsifying a number or creating a fake document would provide a significant boost to the branch’s commissions. He didn’t allow his employees to alter pay stubs or tax documents, though he did allow them to use Wite-Out to alter the monthly benefit amounts listed on a couple of elderly borrowers’ Social Security award letters.

He learned from his colleagues that one of the best ways to game the system without endangering yourself too much was to employ what they termed the “Whoops Technique.” If a borrower had an annual income of $56,000, for example, he might instead report it as $66,000. If somebody in underwriting caught the discrepancy, he could explain that it was a typo— a single flubbed keystroke.

If a borrower really couldn’t afford the deal Ameriquest was writing for them, Paules learned, there were ways around that, too. As long as borrowers made their first payment, the loan officers and managers who’d put together the deal could collect their commissions.

If you gave a borrower enough cash out of the deal, they could afford to make their monthly payments for a little while, at least. Another way to ensure the borrower could make the first payment was to work out a deal with the title company that helped collate the final loan documents. The title company could slip an extra charge onto the customer’s initial loan balance, and then book a credit for that amount to serve as the customer’s first payment. The best part was that this sly arrangement also allowed loan officers to promise mortgage applicants that Ameriquest would make their first payment for “free.”

Once Paules started taking shortcuts and playing around in what Ameriquest workers called the “gray area,” it was hard not to go further. “An inch becomes a yard,” he recalled. “And a yard becomes ten thousand yards real quick.” Many of the tactics that Ameriquest employees used spread informally, through back channels and over break room bull sessions. Simply by hinting that top-performing Ameriquest branches were cutting corners to post big production numbers, Paules could nudge his underlings into employing a bit of their own derring-do to bring in loans. If somebody wasn’t figuring it out for themselves, he paired them with an experienced coworker who could demonstrate the tricks of the trade.

For those who’d already become proficient at these sleights of hand, he used various incentives to encourage them to push their production ever higher, including one that he’d learned at his first management seminar with the company: the side wager. Paules approached two of his salesmen with a proposition. Like Paules, they were young and wild. They liked to party. He promised the pair that if they could top their previous monthly bests, he’d stay after hours with them on the last business day of the month and host a private party for them— complete with a stripper. The pair won the bet, and their party. The next month, Paules increased the stakes. If the two salesmen could once again set personal records, he’d hire two strippers. Again, the salesmen beat their goal and Paules rewarded them—and himself—with an alcohol- fueled celebration in the office that didn’t let up until early the next morning.

The branch was performing so well, many months it outdid all of Ameriquest’s other Pennsylvania locations combined. Paules earned $170,000 in his first eight months at Ameriquest, more than he’d pocketed in four years at American General. After fourteen months as a branch manager, Paules was promoted to area manager. He was now overseeing his old branch and five others in the state. He hadn’t made it to his thirtieth birthday yet, and he had six branch managers, forty loan officers, and various support staff reporting to him.

Higher up the line, Ameriquest’s senior management put policies in place that encouraged managers to prod their employees to squeeze as much profit out of borrowers as possible, even those who had solid credit histories. The company awarded bonuses to area managers, Paules said, if more than 80 percent of the loans produced under their supervision included a “prepayment penalty”—a nasty surprise tucked away in loan contracts that could cost borrowers thousands of dollars if they tried to refinance and get away from Ameriquest. Hitting that target, he said, could put another $5,000 a month in his pocket.

Management also controlled employees by keeping count of just about everything they did. It counted the number of loans made each month by every branch and every loan officer, tracked how much revenue the sales reps had built into the deals, even noted how many phone calls reps were making in any given time span. The company’s computer system allowed senior executives to monitor loan officers’ telephone usage. It wasn’t unusual for Paules to pick up the phone and find his regional manager on the other end of the line, demanding to know why a particular loan officer had only made, say, eight sales calls in the past hour. Paules’s job was to go out and let the salesman know he better get himself into gear.

Paules generally didn’t find too much cause to yell at the people who worked under him—they were fun to party with and they were making him lots of money. But the pressure got to him a few months into his tenure as area manager. He was demanding more and more volume from his sales corps. Near the end of one month, his branch managers assured him that he could expect big numbers for the month. Paules reported the projections up the chain of command. When things shook out, though, production for the six branches was far below what he’d predicted. His regional manager berated him. In turn, Paules summoned all of his branch managers to a conference call and screamed at them like he never had before. His face grew a deeper shade of purple with each expletive he spat out. “Get out of your fucking glass offices and get out on the fucking floor with your fucking people!” If their salespeople didn’t start producing, he told the managers, the solution was simple: get rid of them and hire someone else. If the loan officers couldn’t close loans, the branch managers needed to step in and do it for them. Paules later calculated that he’d set a personal record: he’d used various forms of “the f-word” perhaps five hundred times in the fifteen to twenty minutes he was on the phone. Only later did one of his managers confess: Paules had been pushing them so hard that they’d been afraid to tell him the truth, and instead had given him rosy projections for how loan volume was shaping up for the month. They thought they could always find some trick to catch up.

Travis Paules eventually rose to vice president at Ameriquest. After he left the company, he experienced religious awakening that, he said, prompted him to give us his carousing and “wickedness.” He wrote two books and began looking for publishers. The first one was an autobiographical novel—the main character is named “Trevor Palmer”—that he titled Whiteout, an allusion to Ameriquest’s tradition of altering and fabricating borrowers’ paperwork. The second manuscript was a memoir of his spiritual journey. He titled it 180.