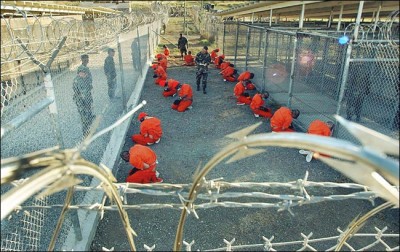

Indefinite Detention without Charge: Habeas Corpus and the Continuing Role of the Guantánamo Bay Prison

“It’s a long way from being closed.” -Gen. John F. Kelly, US Southern Command, Joint Task Force Guantánamo, Sep 1, 2014

The existence of Guantánamo Bay is a reminder that indefinite detention is a species of population control that is here to stay. The reminder that there is such a thing as a Bill of Rights serves merely as a minor prick of conscience, the distant moral waving of a flag. Laws are there, after all, to be circumvented.

Guantánamo has become a modern penological obsession, the avenue for freedom lovers to be nasty and indifferent to those inconvenient facts that a legal system provides. It is an excruciating legal exception that spars or keeps company with the very idea that the dignity of a prisoner, even if overseen by authorities of a democratic state, just might matter. The argument that has come out from the minds of such individuals as Jason Yoo is that exceptionalism mandates its own logic. Bang people up because they wear a different uniform or serve under an inscrutable flag or ideology. Refuse an individual a hearing. Dance around the Geneva Conventions.

Exceptionally dangerous people, it follows from such flawed logic, require exceptionally severe controls and reprimands. In 2009, the Obama administration’s Guantánamo Review Task Force held that an “indefinite detainee” was someone against whom no evidence was had in terms of war crime or other offence, but could not be released. As Carol Rosenberg observed darkly in Foreign Affairs (Dec 14, 2011), “The only guaranteed route out of Guantánamo these days for a detainee, it seems, is in a body bag.”

The longer Guantánamo has remained, the more of a reminder it has become. It is a monstrous finger of doubt, pointing at the US judiciary and legal establishment. It is a calling card for profligacy – $800,000 being spent on average on keeping each detainee alive. Its existence has created a new taxonomy of detention. Medical facilities are ill-equipped to deal with critical illness, with the Pentagon holding it lawful to refuse sending prisoners for emergency treatment. The decision was made after requests by the State Department to Latin American countries “that could receive and treat detainees in emergency situations.” The requests were coolly rebuffed.

The inmates have done their best keep up appearances of trouble. Hunger strikes, and retaliatory force feeding rituals on the part of the authorities, have become common. The New York Times reports that, “The unit that houses the most notorious detainees is built on unstable ground – a floor is described as buckling”. Even the structure wants to give way.

The United States has been doing the rounds in asking the Latin American world to step up and shovel a bit for Uncle Sam. President José Mujica of Uruguay, had been called by Obama’s appendage, Vice President Joe Biden, to do some work on the subject: accept a various number of detainees.

This has been the game of the Obama administration ever since it made that long since broken promise that the detention facility needed to be closed. Congress has been tardy on facilitating that, as have other officials. Representatives on the Hill have been tightening the purse strings, feeling that trials for such captives on US soil should not take place. Moves to relocate some prisoners to a land based version of Guantánamo, located in Illinois, were also foiled.

As Rosenberg observed with dripping irony, “In a strange twist of history, Congress, through its control of government funds, is now imposing curbs on the very executive powers that the Bush administration invoked to establish the camps at Guantánamo in the first place.” No one, it seems, wants to deal with the damaged cargo.

Even after four days of negotiations, nothing came to pass. Mujica’s teeth had begun to rattle at the political implications of accepting the detainees. A poll conducted in July showed that 64 percent of Uruguayans were opposed to any plans of granting the prisoners refugee status. The plane intended for the transfer, a C-17, left empty. Subsequently, vice secretary to the presidency, Diego Canepa, explained that he did not “believe the process will be completed in the next two or three months” (Reuters, Sep 2). Indefiniteness has ceased being rhetorical.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: [email protected]