Impoverishing Ukraine: “Western Political and Business Interests integrated into the Ukrainian State”

Part II of "Impoverishing Ukraine: What the US and the EU Have Been Doing to the Country for the Past 30 Years"

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name.

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

This article was originally published in March 2022.

Read Part I:

Impoverishing Ukraine: What the US and the EU Have Been Doing to the Country for the Past 30 Years

By , July 18, 2023

In addition to breaking up whatever was left of Soviet-era nationalized property and the social welfare state, austerity measures were aimed at disciplining Ukraine’s oligarchs. While their wealth was accumulated on the basis of the country’s integration into the world market, and thus made possible and sustained by the centers of global capital, investors from the West hesitated to descend directly into the dog-eat-dog world of Ukrainian big business, where bribe-taking, ever-changing economic laws, tax rates that on paper sometimes exceeded profits, and the use of bankruptcy for profiteering were rampant.

“[O]mnipresent lawlessness were damaging for foreign relations, political and trade. Western investors from the USA, the EU and particularly Germany (Ukraine’s strongest EU-isation backers) became ‘disenchanted with the country,’” notes Yurchenko. Still, they salivated at the prospect of getting access to tens of millions of consumers and wage-labor that was cheap and skilled. According to Yurchenko, “In a personal interview with the Corporate Europe Observatory think-tank, the former Secretary General of ERT, Keith Richardson, said that the demise of the USSR was as if they ‘have discovered a new South-East Asia on the [EU] doorstep.’”

Concerned not just about the loss of potential investment opportunities in Ukraine but also the geopolitical future of the country, the United States and Europe responded. First, a whole number of business associations and advisory groups—American Chamber of Commerce (ACC), Centre for US-Ukraine Relations (CUSUR), US-Ukraine Business Council (USUBC), the European Business Association (EBA), and the Centre for International Private Enterprise (CIPE)—were either created or mobilized for the purposes of, in the words of the EBA, “discussion and resolution of problems facing the private sector in Ukraine.”

These institutions were staffed with representatives from major Western corporations and Ukraine’s business elite, with many sitting on more than one board. By 2010, 105 of the world’s top 500 transnational corporations were active in them. They sought out, or even established, lobbying groups and advisory councils active in Ukraine’s government.

These include such bodies as the Investors Council under the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, the Working Group of Justice (co-chaired by the European Business Association) under the Ukraine’s Ministry of Justice, the Working Group on Tax and Customs Policy (also co-chaired by the EBA) under the country’s Ministry of Finance, the Foreign Investment Advisory Council of Ukraine (FIAC) under the president of Ukraine, and the Public Councils that are within different ministries and state committees.

Over time, the lobbying groups and advisory councils, according to Yurchenko, collectively got their hands into all of the following areas of Ukrainian governance; the “reduction of state control over economic activity and marketisation alike”; the “simplification of import and export procedures, harmonisation of regulations with the EU in IT and electronics sector, revoking of medication advertising ban, creation of State Land Cadastre in preparation for land privatisation, simplification of market entry for pharmaceutical and insurance companies from the EU”; and “market reform; fiscal and tax policy; banking and non-banking financial institutions and capital market.”

Furthermore, being housed in government agencies, these groups did not just make suggestions as to how Ukraine ought to transform its economy, they were involved in the drafting of law and strategy documents laying out state policy. In short, there is not even one degree of separation between Ukrainian governance and Western corporations, financial interests, and state power.

Between 2006 and 2013 alone, Yurchenko found upwards of 50 instances of “successful lobbying” by just the European Business Association—in other words, the EBA’s suggested policies became Ukrainian law. The Americans have also had their direct means of leverage. The Centre for International Private Enterprise, one of the many lobbying organizations active in Kiev, “serves as a bridge agency between the US Congress and Ukraine’s authorities by proxy of ACC (American Chamber of Commerce). The Centre is run by the Chamber but is in fact one of the four programs of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) that is funded by the US Congress,” notes the scholar.

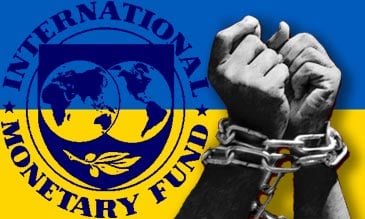

As Western political and business interests have increasingly been integrated into the Ukrainian state, the IMF, other foreign lenders, and the EU have used the ongoing crisis in the country’s economy to pile on the pressure. They have regularly held back on releasing loans or signing trade agreements because Kiev has not privatized and cut enough. When, in order to get the promised money, the government has pushed through the required measures, the outcome for the population has been devastating.

An April 2009 article in the New York Times devoted to Ukraine’s failure, yet again, to meet the requirements of foreign lenders noted that while tens of thousands of jobs had been axed in the country’s industrial towns in the east, bankers viewed it as still not enough.

In Donetsk, “unemployment has officially almost doubled, to 67,500, in the past two months, and the authorities suspect that up to one-third of the 1.2 million registered workers are toiling for a small fraction of their nominal salary,” wrote the newspaper, adding, “In Makeevka, with 400,000 residents, just outside Donetsk, the Kirov factory laid off nearly all its workers in December and January. Now, an average of four people vie for every job. In nearby towns, that ratio soars to 70 or 80 people for every available job, officials say.”

But, citing the comments of a bank analyst in Kiev, the Times observed that still more was expected. Another steel producer in Donetsk, the analyst said, “could easily cut 20,000 to 25,000 people and keep the same output.”

As part of the process of making Ukraine’s economy “more competitive,” the IMF and the EU have demanded the raising of the retirement age, the ending of fuel subsidies that enable households to afford to heat their homes and cook their meals, and the selling-off of the country’s highly profitable timber and agricultural lands. The latter in particular has been long sought, as Ukraine has 25 percent of the world’s “black earth,” some of the most naturally fertile soil in the world.

All of this and more have now been achieved. A 2017 study of Ukraine’s garment industry published in the Journal for Labour and Social Affairs in Europe noted that the Kiev government has introduced the following measures in response to the demands of the international financial institutions and EU representatives over the last several years. It has:

- Frozen the legal minimum wage and stopped adjusting it to the cost of living.

- Reduced social welfare payments and pensions by ending cost of living indexing.

- Changed the labor code to restrict union access to workplaces, make the disclosure of “commercial secrets” grounds for dismissal, require unionized workers to agree to overtime, end limits on the number of overtime hours workers must accept, permit factories to monitor workers using cameras and other technologies, and end the requirement that unions agree to a layoff.

- Increased utility charges dramatically.

- Placed a moratorium on inspections, including labor inspections, in small businesses. (This resulted in the growth of wage arrears from 1.3 million hryvnia in 2015 to 1.9 million in September 2016.)

- Decreased employers’ mandatory social insurance contributions, thereby ensuring there is less money for social services and pensions.

- Cut the number of public sector employees.

- Canceled family payments for childbirth, childcare and schools.

- Closed hundreds of hospitals.

- Stripped higher education and cultural institutions of funding.

As the authors of this study note, all of this is extremely unpopular with ordinary people. Polls have found that 70 percent of citizens are upset about the growth of inequality, 58 percent about job loss, and 54 percent about “interference of western countries in the governance of Ukraine.”

But this continues unabated. The ongoing assault on Ukraine’s health care system has been particularly severe. Due to demands from the IMF and the terms of Ukraine’s EU Association Agreement, the country has been implementing health care reforms. On the grounds of increasing “efficiency,” it stopped paying medical institutions on the basis of their number of beds and instead on how many patients they treat. This has resulted in the layoff of an estimated 50,000 doctors and the shuttering of 332 hospitals, with rural areas being especially hard hit and left, for all intents and purposes, without medical services.