Down the Imperial Memory Hole with Venezuela

In George Orwell’s 1984, the dictatorship of Oceania controlled perceptions by continuous propaganda broadcast through the “telescreen” and constant updating of news print so that the past would conform to the lies of the present. The device used to discard any document contradicting the fakery of the present was called a “memory hole.”

Orwell was acutely aware of the fact that empire thrives on imperial amnesia and constant historical revision of the past by the powerful. He knew that citizens would be much easier to control if they were forced to live in an eternal present — a place where it would be impossible to critically assess and compare today’s world by looking at what happened yesterday and the day before.

In the 21st century, we have constructed our own kind of Orwellian memory holes. The global nexus of economic and political powers in neoliberal corporate capitalist states and international bodies tend to view critical and historical consciousness as an impediment, if not an outright threat, to their hegemony. The reason is obvious: an informed, critical consciousness is the foundation upon which any flourishing democracy is built — where the “political” is understood as government of, by and for all citizens, not merely in the interests of the wealthy or powerful few.

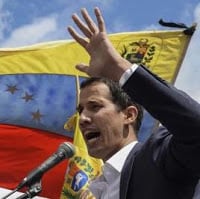

No doubt, this was why the Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg News and The New York Times, could, without a hint of irony, claim that U.S. democracy was “undone” because a foreign power put Trump into office, while simultaneously praising Venezuela’s opposition leader Juan Guaidó after he received a directive from Vice President Mike Pence that he should just forget about elections and declare himself president.

Gore Vidal once said, “ … we are permanently the United States of Amnesia. We learn nothing because we remember nothing.” Yet, even in the U.S., it is still possible to uncover a “history of the present” where Central and South America are concerned. If you are prepared to put in the necessary time and effort, you can discover the truths and realities of a past that many of those in power would rather you just forget.

Here’s one of the key geopolitical lessons you’ll learn: The U.S. empire and its regime change proxies — the Organization of American States (OAS) and the Lima Group — have never had much interest in or respect for the sovereignty of any Central or South American country that did not show the proper level of obedience to the U.S. government and corporate interests. This imperialist perspective goes back to the 1823 Monroe Doctrine when the U.S. determined that only it had the moral authority to say who should be in power in its “own back yard.”

Reacting to the Monroe Doctrine, Simon Bolivar, the great revolutionary who helped South America gain independence from Spanish rule, accurately predicted that the U.S. was “destined to plague and torment the continent in the name of ‘freedom.’” Bolivar’s prediction has been borne out time and again as the U.S. imposed economic sanctions and funded right-wing military dictatorships in Honduras, Panama, Cuba, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Chile, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador and Venezuela.

Pence’s intervention in the affairs of a foreign state follows on the heels of a long tradition of U.S. economic and military interventionism in Central and South America. The dictators put in place — from Nicaragua’s Anastasio Somoza García, Honduras’s Roberto Suazo Córdova and Roberto Micheletti, Panama’s Manuel Noriega and Chile’s Augusto Pinochet — all had one and only one objective: to turn what were once social democracies into subservient satellite states so that the U.S. might then gain access to resources and oil, privatize state assets, and impose what journalist and author Naomi Klein has accurately described as “neoliberal shock therapy.”

But empire is also aided and abetted by the hypocrisy of allies that cower before imperialist states while pretending that they subscribe to the norms of international law. Canada, Austria, Portugal, Britain, Denmark, France, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands and Sweden have all endorsed Guaidó’s claim to a de jure presidency, while Italy, Mexico, Ireland and Greece have, so far, refused to go along. The latter group of countries likely concluded what anyone with even a minimal understanding of international law would be forced to conclude: Guido’s actions were an illegal and undemocratic attempt to usurp a democratically elected president. Despite this, the Lima Group has not only signed a Declaration which recognizes Guaidó as the de jure interim president, it also included in this declaration a measure that prevents the Maduro regime “from conducting financial and trade transactions and doing business with their oil, gold, and other assets.”

In a Washington Post opinion piece, Guaidó outlined the case for his self-appointment as de jure president of Venezuela. The only problem is that the de jure constitutional foundation Guaidó relies upon expressly designates the vice president — not the president of the National Assembly — as the next in line should the president not be able to carry out his duties. Article 233 of Venezuela’s constitution also elaborates just when this can occur:

The President of the Republic shall become permanently unavailable to serve by reason of any of the following events: death; resignation; removal from office by decision of the Supreme Tribunal of Justice; permanent physical or mental disability certified by a medical board designated by the Supreme Tribunal of Justice with the approval of the National Assembly; abandonment of his position, duly declared by the National Assembly; and recall by popular vote.

One need not be a constitutional expert or even a lawyer to see that not one of the six criteria apply with respect to the legitimacy of Nicolás Maduro’s presidency: Maduro has not left this world, he has not resigned, abandoned his position or been removed by the Supreme Tribunal. He has no permanent physical or mental disability, and finally, has not been recalled by popular vote.

Moreover, even if one of the above events occurred, it would still be the case that an election would have to be held within 30 days of an interim president being appointed — something which is obviously not of great concern to Guaidó, since he has already declared himself the de jure, if not de facto president of Venezuela.

Guaidó is not the de jure president — unless what is meant by de jure is someone who declares that he is a “law unto himself.” Think about Guaidó in this context for a moment. Someone who has never been elected by anyone can declare himself as “interim president” so long as he is recognized by political leaders that exist outside of his or her country. This is assumed to be in keeping with the notion of “popular sovereignty,” with democracy, with constitutional legitimacy?

What of Maduro’s refusal of so-called humanitarian aid from the U.S.? Former United Nations rapporteur Alfred de Zayas has said that a country which imposes illegal sanctions and has waged an economic war on Venezuela for 20 years is certainly not giving aid in good faith. One need only look at the history of U.S. “aid” to Central and South America to know that it is rarely, if ever, “humanitarian.”

It was that wonderful “humanitarian” and “fierce advocate for human rights and democracy” Elliot Abrams who, in 1987, cooked up the U.S. plot to use a humanitarian program to send military arms to the contra death squads in Nicaragua. Abrams, Trump’s recent appointee as special representative for Venezuela, might be the textbook case of a war criminal. A well-known supporter of torture, death camps and decapitation, Abrams did everything he could to ease the way for Guatemalan dictator Efraín Ríos Montt to commit acts of genocide against Indigenous people of the Ixil region; he lied to Congress about the Iran-Contra scandal; he propped up a dictator in El Salvador and cheered on the military coup against the democratically elected government of Venezuela in 2002.

So long as Abrams — one of the most radical and depraved architects of U.S. foreign policy in Central America — is the U.S.’s “special envoy,” you can be fairly sure that there will not be anything remotely “democratic” or “humanitarian” in U.S. aid to Venezuela.

OK then, what about the charge that the 2018 election in Venezuela was “fraudulent and undemocratic”? Article 350 of Venezuela’s constitution calls for citizens to “disown any regime, legislation or authority that violates democratic values.” For this to happen, both the national and international community must unite behind a transitional government that will guarantee humanitarian aid, ensure that the rule of law is restored and begin to hold democratic elections. However, there just isn’t any unity of opinion outside or inside Venezuela, so the very idea that this article is being relied upon as grounds for recognizing Guaidó as the de jure president is completely unfounded.

Why? Venezuela is a federal presidential republic, and like most democracies, it is grounded on the separation of powers, with government divided into three branches: legislative, executive and judicial. The legislative branch, or National Assembly, declared Maduro illegitimate on the day of his second inauguration. However, the judiciary, the Supreme Tribunal of Justice (the highest court of law in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, empowered to invalidate any laws, regulations or other acts of the other governmental branches conflicting with the constitution) has countered that this latter declaration was itself unconstitutional.

This is the sort of internal constitutional conflict that any country has the right to work out for themselves, without any sort of external pressure or interference. Are there Venezuelans who oppose the Maduro government? Of course, there are — and there is no shortage of newspapers in Venezuela fiercely critical of the Maduro regime. That is not likely something most “dictators” would permit. The problem is that the international media focused almost exclusive attention on opposition protests. Those who still hold to the ideals of the Bolivarian revolution grasp that their present woes are not only a result of Maduro’s policies, but much more the consequence of debilitating U.S. economic sanctions which are precisely intended to accelerate the collapse of Maduro’s government. What Venezuelans need now is not more imperialist economic interventions or declarations that Venezuela is a national security threat, but rather some level of recognition that the 67 percent of those who supported Maduro might be capable of determining what is best for their country.

The National Electoral Council declared Maduro the winner of the elections and president of Venezuela until 2025. Secondly, a majority of authorized parties that ran were not supporters of Maduro; 11 of them were opposed to his government. Those parties prevented from running were not excluded because they opposed Maduro, but because they violated election and constitutional law. Thirdly, many of the right-wing parties that did not run were told not to do so by the U.S., which argued that their participation would give legitimacy (i.e. democratic standing) to an election that the U.S. declared in advance was not going to be democratic or fair. Fourthly, not only did the U.S. encourage opposition parties to boycott the 2018 election, they also demanded that the domestic opposition parties in Venezuela tell the United Nations not to send election observers — against the wishes of the Maduro government. In short, the U.S. did everything possible to undermine the 2018 Venezuelan election, precisely so they could later claim that it was “fraudulent and undemocratic.” That has essentially been the norm since the very early days of Hugo Chavez.

Chavez did the unthinkable from the point of view of any goodthinkful neoliberal: he nationalized Venezuelan oil for the benefit of the Venezuelan people; he defied the U.S. and impertinently stood as a socialist counter-example for other Latin American populations to emulate. That kind of political and economic independence simply could not be tolerated by the corporatized U.S. empire.

Such upstart socialist initiatives were enough for Venezuela to be considered an “extraordinary national security threat” and Chavez to be designated a “dictator” — despite being elected with 56 percent of the vote in 1999 and later elected with 59 percent support in 2004. Would the same conclusion be drawn with respect to two recent U.S. presidents (George W. Bush and Donald Trump) where the winner of the election actually lost the “popular vote”— a more direct and democratically representative assessment of voter support?

There may well have been irregularities in the last Venezuelan election. Then again, there have been well-documented irregularities, voter suppression and even fraud in a good number of U.S. elections. What do you imagine would have happened in 2000 had Al Gore declared himself the de jure president of the United States and Austria, Canada, Portugal, Britain, Denmark, France, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands and Sweden recognized him as such? Any such suggestion would be laughable.

None of this is meant to excuse the Maduro government — nor, for that matter, the Chavez government. Both are guilty of mismanaging the economy and relying almost exclusively on oil revenues rather than diversifying Venezuela’s economy. Their narrow economic approach certainly gave rise to a state of hyperinflation, a dysfunctional currency problem and the inevitable political corruption that follows from all this. However, it is also crucial to understand that oil companies, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the United States held Venezuela’s economy hostage before Chavez even came to power. As economist Michael Hudson reminds us, what Chavez was unable to do was “clean up the embezzlement and built-in rake-off of income from the oil sector. And he was unable to stem the capital flight of the oligarchy, taking its wealth and moving it abroad — while running away themselves.”

By further imposing economic sanctions that prevented Venezuela from gaining access to its U.S. bank deposits and the assets of its state-owned Citgo, the U.S. made it virtually impossible for Venezuela to pay its foreign debt. This forced the Chavez government into default, and at the same time, became the perfect excuse to foreclose on Venezuela’s oil resources and seize its foreign assets.

The ultimate goal of U.S. foreign policy has always been to impose economic shock therapy on weaker nations so that other social democracies in Central and South America don’t get the idea that they can use their own natural resources for the benefit of their citizens. Indeed, Trump’s national security adviser, John Bolton, has made no secret of the fact that U.S. intervention in Venezuela is not about democracy, but about oil and the exploitation of Venezuela’s natural resources. This became all too evident after Guaidó began to make moves to privatize the country’s state-owned oil company by seeking money from the economic arm of global neoliberalism: the IMF.

It is indeed time for Maduro to open a new dialogue with both those who have been left out and other progressive voices; it is time for him to put forward a new economic program that meets the crisis of inflation, and speaks to the pain and dislocation of ordinary Venezuelans. This would require the kind of thoughtful diplomacy that has always been in short supply in U.S. foreign relations. The current strategy of the U.S., the OAS and the Lima Group is to ensure that Maduro is unable to resolve Venezuela’s problems. With help from a subservient mainstream media and compliant Western states, they will try their best to make the Bolivarian revolution disappear down the memory hole. We must not let that happen.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Fred Guerin holds a Ph.D. in philosophy and teaches philosophy part-time at Vancouver Island University in Powell River, British Columbia.

Featured image is from Club Orlov