Hurricane Harvey: 650 Energy and Industrial Facilities May Have Been Exposed to Floodwaters

New Map Shows Energy, Industrial, and Superfund Sites

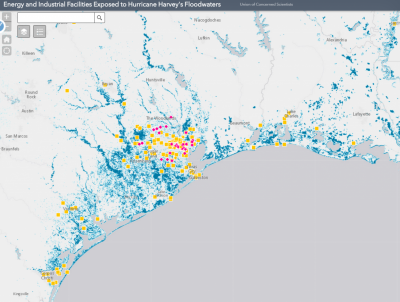

A new UCS analysis shows that more than 650 energy and industrial facilities may have been exposed to Hurricane Harvey’s floodwaters.

Harvey’s unprecedented levels of rainfall in Texas and Louisiana coasts have exacted a huge toll on the region’s residents. In the weeks and months ahead, it is not only homes that need to be assessed for flood damage and repaired, but also hundreds of facilities integral to the region’s economy and infrastructure.

To highlight these facilities, the Union of Concerned Scientists has developed an interactive tool showing affected sites. The tool relies on satellite data analyzed by the Dartmouth Flood Observatory to map the extent of Harvey’s floodwaters, and facility-level data from the US Energy Information Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency.

The tool includes several types of energy infrastructure (refineries, LNG import/export and petroleum product terminals, power plants, and natural gas processing plants), as well as wastewater treatment plants and three types of chemical facilities identified by the EPA (Toxic Release Inventory sites, Risk Management Plan sites, and Superfund sites).

Chemical facilities potentially exposed to flooding

Hurricane Harvey may have exposed to flooding more than 160 of EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory sites, 7 Superfund sites, and 30 facilities registered with EPA’s Risk Management Program.

The Gulf Coast is home to a vast chemical industry. The EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) program lists over 4,500 facilities in Texas and Louisiana alone that are required to report chemical releases to the environment.

Before the storm hit, many facilities shut down preemptively, releasing toxic chemicals in the process. In the wake of the storm, explosions at Arkema’s Crosby facility highlighted the risks that flooding and power failures pose to the region’s chemical facilities and, by extension, the health of the surrounding population.

In the Houston area, low-income communities and communities of color are disproportionately exposed to toxic chemicals. Our analysis shows that over 160 TRI facilities, at least seven Superfund sites, and over 30 facilities registered with EPA’s Risk Management Program were potentially exposed to floodwaters. The number of flooded Superfund sites may be even higher than the map shows, as indicated by preliminary reports from the EPA and other sources.

Though most of the impacts from this exposure remain unknown, the risks include compromised facilities and the release of toxins into the air and receding floodwaters.

Energy infrastructure

In the week since Hurricane Harvey reached the Texas coast, disruptions to the region’s energy infrastructure have caused gas prices to rise nationally by more than 20 percent.

Our analysis finds that more than 40 energy facilities may have been exposed to flooding, potentially contributing to the fluctuations in gas prices around the country. As of yesterday, the EIA reports that several refineries have resumed operations while others are operating at reduced capacity.

More than 40 energy facilities–including power plants and refineries–may have been exposed to Hurricane Harvey’s floodwaters.

Wastewater treatment

Wastewater treatment facilities comprise the bulk of the facilities (nearly 430) that we identify as potentially exposed to flooding. The EPA is monitoring the quality and functionality of water systems throughout the region and reported that more than half of the wastewater treatment plants in the area were fully operational as of September 3.

With floodwaters widely reported as being contaminated with toxic chemicals and potent bacteria, wastewater treatment facilities are likely contending with both facility-level flooding and a heightened need to ensure the potability of treated water.

Nearly 430 wastewater treatment facilities may have been exposed to flooding during Hurricane Harvey.

About the data

It is important to note that the satellite data showing flood extent is still being updated by the Dartmouth Flood Observatory, and that we will continue to get a better handle on the extent and depth of flooding as additional data become available from sources such as high water marks from the USGS.

As of Tuesday, DFO Director Robert Brakenridge stated in an email that they believe the data to be fairly complete, including for the Houston area, at a spatial resolution of 10 meters. Given uncertainties in the flood mapping as well as in the exact locations of each facility, it is possible that this map over- or underestimates the number of affected facilities. It is also possible that facilities, while in the flooded area, were protected from and unaffected by floodwaters.

Kristina Dahl is a climate scientist who designs, executes, and communicates scientific analyses that make climate change more tangible to the general public and policy makers. Dr. Dahl holds a Ph.D. in paleoclimate from the MIT/WHOI Joint Program in Cambridge and Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

All images in this article are from the author.