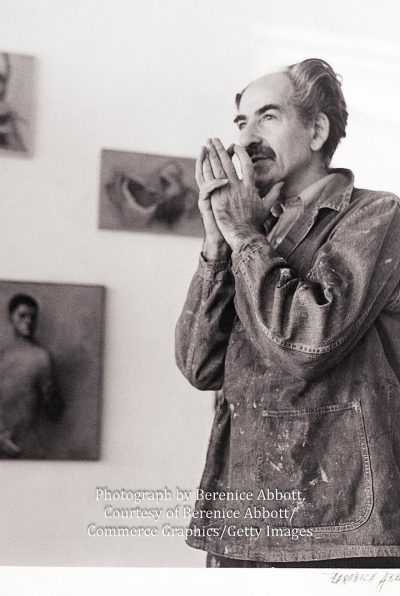

Humanism in Painting: Remembering the Art of Symeon Shimin. NY Whitney Museum

As New York’s Whitney Museum exhibits the work of the great Mexican muralists – Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros – this is a moment to revisit and reflect on the work of Russian-born artist Symeon Shimin. During his life, Shimin illustrated over 50 children’s books, including two that he authored himself; his masterpiece, however – influenced in part by ‘Los Tres Grandes’ – was the mural painting, “Contemporary Justice and the Child” (1936), located on the third floor of the Department of Justice, where it still stands today.

In 2019, Mercury Press International published The Art of Symeon Shimin, an exceptionally fine compilation of his work, featuring not only dozens of gorgeous, high-resolution color plates, but a short autobiography by the artist, as well as essays by noted art journalists Josef Woodard and Charles Donelan. Edited and curated by the artist’s daughter, Tonia Shimin, this book was more than 30 years in the making, and represents the first complete collection and overview of Shimin’s fine art.

While he enjoyed a long and successful career as an illustrator and commercial artist for Hollywood films (including the original, iconic poster for Gone With the Wind), Shimin never quite received the recognition that his work truly merited. Undoubtedly, this was largely due to the fact that Shimin was fundamentally a figurative and representational painter working at a time when various forms of modernism and avant-garde art, such as abstract expressionism, were ascending and gaining influence.

Mural by Symeon Shimin, Contemporary Justice and the Child, Tempera on Canvas, 1936-1940, Awarded by competition for the Public Works Arts Project, Department of Justice Building, Washington DC

The book provides exquisite reproductions of over 70 paintings, including a detailed look at the gestation and development of “Contemporary Justice and the Child.” Commissioned by the Public Works Art Project, Shimin understood that this was, as he put it, “not a slight matter” – it was the artist’s “moment of truth,” as Donelan observes, and he would choose his subject both “carefully and wisely.” Having travelled to Mexico in the 1930s, and soaked up the Mexican Mural Renaissance, Shimin was committed to seeing his work serve the cause of social justice, not only as a condemnation of child labor, but as a meditation on racial and gender equality, the social pursuit of knowledge and science, and much else besides.

Shimin arrived with his family at Ellis Island in 1912, when he was ten-years old; and growing up in Brooklyn, he learned first-hand what it meant to be exploited at an early age, delivering groceries from five in the morning until six in the evening, for three dollars a week. He sought and found refuge in music, and originally was determined to become a musician. While music would remain for Shimin a life-long passion, that ambition was quickly quashed by his parents, and his uncle, who was himself a “disillusioned composer.” It was not long after this that he discovered his gift for drawing “with fidelity to reality” – and “as if by some mystery it was revealed to me that I am an artist.”

Shimin’s experiences as a child would stay with him and inform his masterpiece, which is, on the left-hand side, about the hardship and injustice endured by countless children subjected to desperate poverty, hunger, and the soul-sapping labor of the factory. A large group of impoverished children are gathered together, drained of color, looking directly at the viewer with mixed expressions of sadness, anger, worry and hopelessness. Above them a large factory stretches endlessly into the distance, topped by three smokestacks that spew their sooty fumes into the darkening sky. In the lower left corner, a tight crawl space is occupied by two young boys, ragged, weary, and half-starved.

The centerpiece and heart of the mural is a young woman, in front of whom stands a wide-eyed boy, presumably her son, whose hands she gently holds in her own. Both figures face the viewer, as if she is offering him to us, to the world; as if she is saying, “Here he is, take him, care for him, and he will do great things.” On the right-hand side we see what some of those things are – the creative, scientific, and athletic pursuits of young men and women, black and white, working and thinking intently together, or engaged in the healthy competition of sport.

The expressivity of hands were crucially important for Shimin – and they constitute a motif running through much of his work, including his great mural. At the bottom center, a large pair of hands are not merely part of the foreground, but actually jut out, almost as if they are part of the viewer’s space, or the hands of the artist himself. One holds a drafting triangle, and the other a compass; and both are oriented towards the right, the hopeful and colorful side of Shimin’s multi-layered mural, hovering above the heads of a young man and woman who study an architectural blueprint.

Shimin was able to convey the wide array of human emotion through the hands no less than through the face of his subjects. In “Lovers” (1980), for example, the faces are almost entirely hidden, but all four hands are visible, and together they manage to carry the nearly monochrome painting and convey all the tenderness, gentleness and warmth of the man and woman. In the extraordinarily powerful “Woman with Hands at Chest” (1973-76), the two clenched fists that the subject brings together above her breast seem to reflect both the grief and determination, the sadness and strength that we find in her striking profile.

Hands figure prominently also in “The Pack” (1959), a painting which is otherwise unique in Shimin’s oeuvre. A profound meditation on violence which brings to mind Hobbes’ assertion that ‘man is a wolf to man’, “The Pack” arose out of the artist’s confrontation with a street gang “that left him injured and traumatized.” In Shimin’s blood red painting, which was shown at the Whitney Museum’s 1959 Annual Exhibition of American Art, the entangled figures appear to be metamorphosizing into hyenas and jackals. At the bottom, an arm lies outstretched on the ground, the palm facing upward, a victim presumably of street violence who now lies surrounded by the pack like a fresh kill.

Symeon Shimin’s art was chiefly concerned with using the human form to express the inner life of the individual, and the weight of existence that each of us carries. Through his portraiture, through his careful observation and representation of the human figure, he was able to find and express the intrinsic value of the human person as such. His work is imbued with a deep and abiding sympathy for the humanity of his subjects, the need we have for each other, for understanding and being understood, with all the difficulty and riskiness that this implies. Shimin always used live models because, he said, “I believe the individual characters to be more meaningful.” That unflagging devotion to the human individual, to the inherent value and dignity of the individual human being is his lasting legacy; and as long as we seek to understand and express the value and significance of human experience as such, there will be a place for artists such as Shimin.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Sam Ben-Meir is a professor of philosophy and world religions at Mercy College in New York City. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.