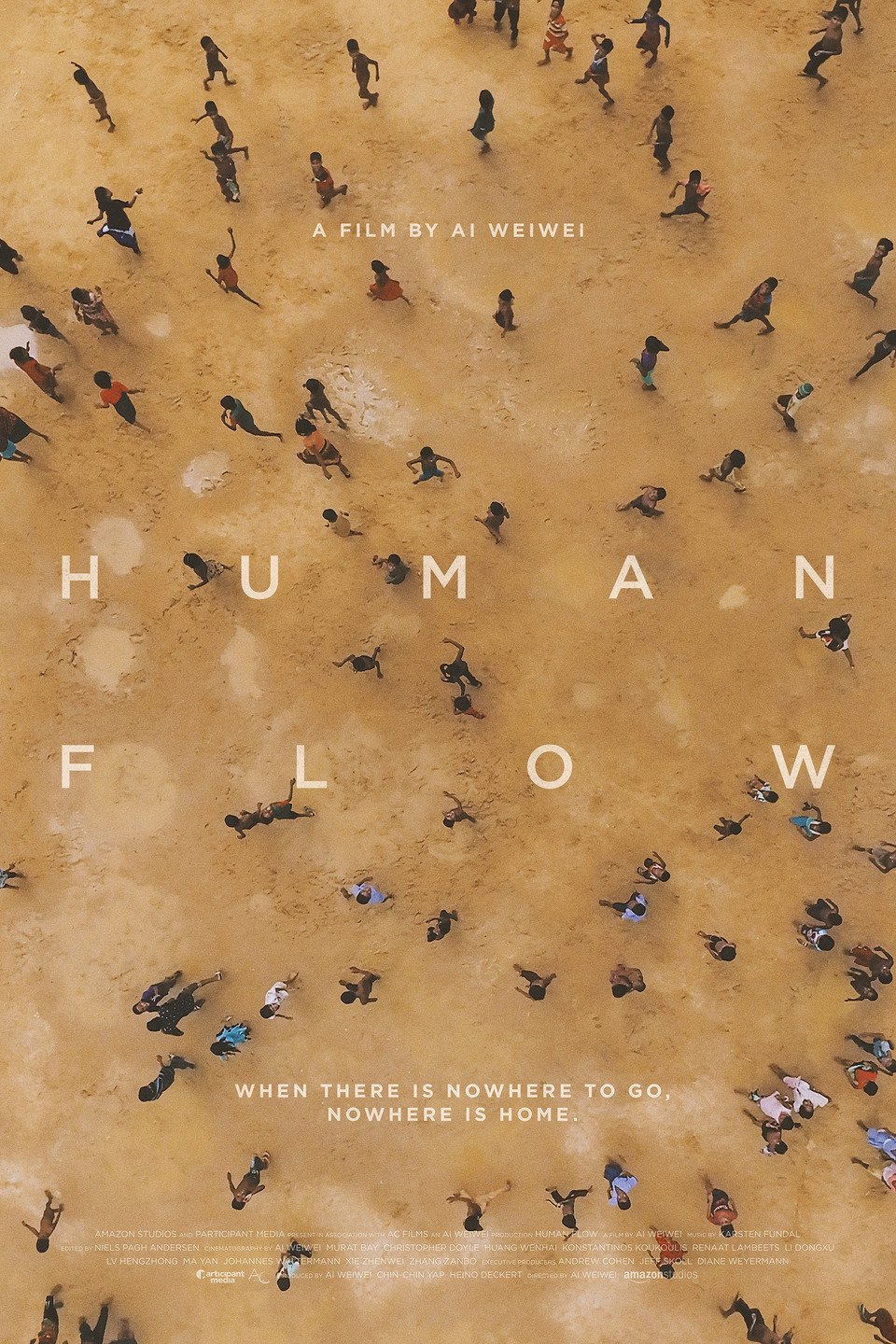

“Human Flow, When There is Nowhere to Go, Nowhere is Home”

Film Director Ai Weiwei Turns His Art/Activism to Global Refugees

Featured image: Ai Weiwei @ 798 Beijing (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

When I received the invitation from Magnolia Pictures to preview a forthcoming film by artist Ai Weiwei, recognizing the name of its celebrated Chinese director, I was eager to screen it. I have a scant impression of the visual extravagance of Ai’s art work, but knew nothing of his film-making before my research for this review. Now I learn of his copious filming explorations resulting in more than 20 video productions between 2003 and 2013, some rather lengthy, e.g. Chang’an Boulevard (10:13 hrs) or Fairytale at 2:33 hrs, and mostly completed in his homeland.

Ai Weiwei’s early videos are largely investigative visual documentations of injustices, tragedies, dissident profiles and autobiographical projects. A prolific artist who also identifies himself as an activist and dissident, Ai gained wide international attention, predictably, when in 2011 he was detained for some 81 days in his city, Beijing.

He works in multimedia, often on a grand scale. This may explain his attraction to the theme of this film, Human Flow@HumanFlowMovie @aiww, due for release October 13th in the USA. More than two hours long, taking us into fourteen refugee camps across more than ten countries from Bangladesh to Kenya to Mexico (notably, this project omits reference to Tibetan or Qinghai refugees from China), employing some 100 staff and 60 translators, Human Flow is of epic scale in more than its title.

Human Flow is essentially a human rights story—a visual statement of the unfulfilled rights – or dreams, if you will– of refugees across the globe. His tens of thousands of subjects—representing tens of millions worldwide–are souls in transit: South Americans slipping across the Mexican border into the USA, Palestinians driven from their lands, Africans escaping from various homelands by boat to Europe, and Middle Eastern families walking into the European mainland. It’s about fences and guards, and waiting huddled families.

Most of those offering testimonials, Ai Weiwei films inside refugee camps. Stark, somewhat formal, on-camera interviews with individuals provide first hand accounts of their victimization, anxiety, and bitterness.

Little of what we witness in Human Flow will be new to anyone following international events. In recent years, with the massive exodus of people from the Middle East into Europe, the military conflicts, the controversial status of undocumented workers, the deaths of thousands crossing the Mediterranean Sea, and subsequent debates about what host counties ought to do, even the most disinterested of us is aware of the “human tide” pressing upon our shores.

Testimonies by refugee families in the film are interspersed with statements by officials– professionals in the refugee business: we hear from doctors inspecting camp conditions, from human rights lawyers citing UN conventions, from a diplomatic Jordanian princess, from Hanan Ashrawi, Palestine’s most articulate representative, from UNICEF’s spokesperson in Lebanon, from Israel’s B’Tselem director, from the Carnegie Middle East director, from a UNHCR spokesman in Kenya. All offer choreographed, disembodied statements about the need for more, more, more…

A short segment with the single politician in the film, Lebanon’s Walid Jumblatt, is noteworthy for its candor. About migrants, Jumblatt declares, “without memory you are nothing”; about refugee management he points to the hypocrisy of international refugee policies. In skimming over Jumblatt’s blunt assessments, Ai Weiwei missed the chance to explore more fundamental issues behind those pompous, exploding human rights’ businesses. He could have offered us a really piercing story, introducing Human Flow with Jumblatt’s provocative assertions followed by dialogue with Jumblatt about the financing of camps, the wars generating these exoduses, the pornographic use of pitiful images of victims, threaded together with the powerful visuals that Ai’s cameras capture. A lost opportunity by a man known for provocative, daring work.

As with his other projects, Ai Weiwei wants us to know he is there: on the ground with sobbing refugees, beside his camera crew at a tense frontier, his hair disheveled by sand-laden desert winds. Here is the anthropologist, there-but-not-there, allowing refugees and images of their environments to speak for themselves, superimposed with an occasional news headline or quote from a Turkish or Arab poet to augment the pictures.

Which brings us, finally, to the images. What is new to our refugee picture are spectacular aerial shots presenting a panorama of refugee living:—we are taken high above an endless, blue sea where a boat laden with escapees slowly moves into the frame; we gaze through a wide angle photo of a camps’ columns and columns of identical, orderly white structures; another aerial encompasses countless scattered huts amid the detritus of their impermanence; we are held beside tents haphazardly pitched at a railway station, dwarfed by an enormous, slowly moving train passing resolutely behind.

This is the “flow”– perhaps more accurately termed “stagnation”– that impacts the viewer more forcefully than faces and statements of refugees and administrators.

Because of the director’s reputation, a lot of people will want to see Human Flow. Still, given Ai Weiwei’s goal of using art to change perceptions, we need to ask: can this film do that?