How US “Good Guys” Wiped Out an Afghan Family

It was 4am when Masih Ur-Rahman Mubarez’s wife Amina called, an unusually early time for their daily chat. When he picked up the phone, he could hear the panic in her voice.

Amina was calling from the Afghan province of Wardak, where she brought up their children while he worked over the border in Iran to support them. She told him that soldiers were raiding their village. Some of them were speaking English. Amina was told to turn off her phone but Masih asked her not to – how would he know they were ok?

The call ended with Masih saying he would call again when things had calmed. But at 9am, when he dialled his wife’s number, her phone was off. He tried again at 9.30am. Still off. Through the whole of that day and the next, he repeatedly called. But Amina’s phone remained off.

It took another day for him to the learn the truth. Relatives avoided his calls or gave vague replies to his questions, until finally his brother broke the news. “He tried to avoid telling me the whole story, but I insisted that he tell me the truth,” Masih recalled in a wavering voice. “He told me to have patience in God – no one is left.”

Image on the right: Masih spent months working alongside journalists to prove who had killed his family

An airstrike on Masih’s house had killed his wife and all his seven children, alongside four young cousins. His youngest child was just four years old.

In the following weeks, as grief consumed Masih, so did an intense need for answers. Who had killed his family and why?

His journey to find out would last more than eight months, pit him against military and government officials, and see him face obfuscation and denials. It would lead him to work alongside the Bureau and journalists from The New York Times, putting together a puzzle piece by piece. Ultimately it would lead to one definitive conclusion – the US military had dropped the fatal bomb.

His story is one window into the struggles faced by families across Afghanistan every day. Airstrikes are raining down on the country, with US and Afghan operations now killing more civilians than the insurgency for the first time in a decade. But getting confirmation of who has carried out a fatal strike is often impossible. An apology, or any form of public accountability, is even harder to obtain.

The US denied repeatedly that it had bombed Masih’s house, or even that any airstrike in his area had taken place. But using satellite imagery, photos and open source content, we proved that denial false. Following our investigation, the military has now admitted that it did conduct a strike in that location, but it still denies it resulted in civilian deaths.

A happy life destroyed

“Prior to my house being bombed, I had a normal life. I was married, had four daughters and three sons,” Masih told our reporter in Kabul. “Our life was full of love.”

Masih was the headteacher in a local school run by a Swedish organisation before financial issues forced him to seek employment in construction in Iran in 2014. He still reminisces about his days in the village of Mullah Hafiz, where he split his time between farming, teaching and his children. “We were so happy,” he says.

Exactly what happened on the day of the strike is not clear. Villagers say that overnight on September 22 2018, bombs were dropped in Mullah Hafiz, which lies in a Taliban-controlled area. The same night, they said, soldiers carried out a raid on the village as part of an operation on a Taliban prison, which was about 200 metres away from Masih’s house. One of the villagers said Taliban fighters had fired on the soldiers from some civilian homes.

A cousin of Masih’s told us he and and other male relatives were taken away and detained, alongside some other villagers. At some point the next morning, a strike hit Masih’s house. When his relatives returned, they found the building flattened. In the rubble were the bodies of Amina, the seven children and their four cousins, they say.

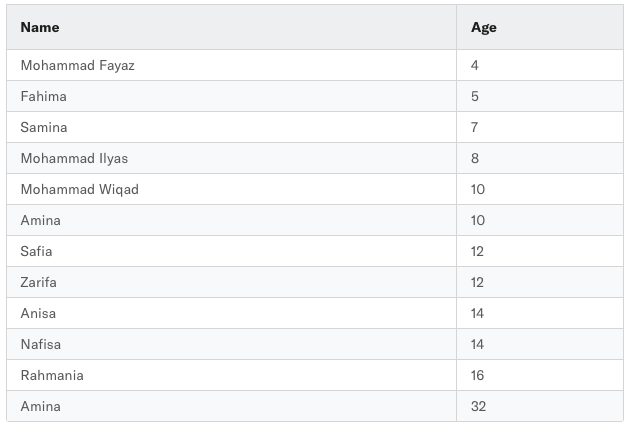

Masih’s children were aged between four and 14 years old; his wife Amina was 32. The cousins, all girls, were aged from 10 to 16.

Clockwise from top left: Masih’s children Mohammad Elyas (8), Mohammad Wiqad (10), Fahim (5), Samina (7) and Mohammad Fayaz (4) all died in the strike, alongside their two elder sisters, Anisa (14), and Safia (12), and their mother Amina (32). (Fahim appears in both photos in the bottom row)Photo supplied by family. We do not have photos of the teenage girls or Masih’s wife Amina

The full list of those who died in the strike

On finding out his family had been killed, Masih returned immediately to Afghanistan. The return journey was tough – having been working illegally in construction in Iran he says he had to hand himself to the Iranian police and wait for deportation. It took him three days to get back to his village. It was then that he began hunting for the truth.

Masih claims government officials acknowledged in private that his family died. However while both the Afghan Ministry of Defence and the provincial police publicly announced in the days following the attack that an operation on a Taliban prison had killed large numbers of Taliban fighters, they did not acknowledge that any civilians died in a strike.

“I have repeatedly told them that it was my children, that it was my wife, that it was my cousins, that they were all civilians and that my house was destroyed,” Masih said. “When they say that they have bombed a [Taliban] prison, they have absolutely not done that.”

Journalists investigate

As Masih was investigating, so was the Bureau. We had independently heard of a strike that had killed multiple children in Mullah Hafiz on September 23, and were trying to establish who had carried it out.

The Bureau has been recording strikes in Afghanistan for over four years. Getting to the bottom of what has happened is often difficult. The attacks mostly take place in remote areas under Taliban control. They are often not reported by local media and neither the US nor the Afghan military is fully transparent.

We faced all these same barriers with this strike. But this time, over the course of several months, working with Afghan reporters on the ground and the Visual Investigations unit of The New York Times, we were able to prove that the US was responsible for a strike which killed multiple children.

Our first step was to contact both the Afghan and the US militaries.

Officials in the Afghan Ministry of Defence told us no one was available for comment.

When we went to the US military, we were met with contradictory statements. Its story changed repeatedly as our reporting developed and the New York Times got involved.

A US spokesperson first stated in October that there were “no connections” between their actions and the allegations of civilian casualties in Mullah Hafiz. In a later email in February, they claimed to have no record at all of a strike in the district on September 23.

In a Pentagon report released this month the strike on Masih’s house was not included in a list of confirmed civilian casualties.

Finally, as we prepared to go to press earlier this week, they admitted they had bombed Masih’s house. Days later, there was yet another statement. American soldiers had reported being fired on from the house, they said, and a strike had been carried out “in self-defence.” But they did not kill Masih’s family, they said.

The military has not told us what information it used to reach its conclusion. It is not uncommon for the US to rely, for the most part, on pre-strike and post-strike footage filmed by aircraft to investigate claims that an air attack has harmed civilians. But when a strike hits a building, as in the case of Masih’s home, it can be difficult to tell what’s under the rubble.

Crucial evidence

Masih wanted the world to know what had happened. Interviews he did with Afghan media led us to contact him, and in April we were able to meet him in Kabul. By this time, he had been knocking on doors for months in search for answers. He had carefully collected evidence he hoped would shine a light on what happened that day.

Some of this helped our investigation. First we needed to do the basics – to verify that a strike had hit his house. We had to do this without visiting the village, because it was not safe for reporters to go to the Taliban-controlled area. From metadata contained in photos supplied by Masih, we were able to obtain the coordinates of his home. We used these to get satellite images which showed the house had been attacked, with the damage consistent with a strike. A team from the Bureau and the The New York Times’ Visual Investigations unit also reviewed photos of Masih’s children’s graves and found satellite images of the burial site. Both the damage to the house and the burial site are only visible in satellite images after September 23.

Crucially, we also were given photos of weapon fragments said to be found at the site of the strike. While most were nondescript, a few pieces had distinctive markings. On one piece we could see what is known as a “CAGE code” – this is a unique identifier given to companies which supply government or defence agencies. This code linked the fragment to a US-based company called Woodward, that makes components for a missile kit known as a JDAM. These enable bombs to be guided by GPS.

Weapons experts then reviewed the photos, and saw something else – the distinctive pattern of four bolts on a tail fin that identified it as part of a JDAM.

We trawled defence and aviation news archives and found the Afghan military did not have capability to use JDAMs. The only other military carrying out strikes in Afghanistan is America’s.

We asked the weapons experts which military could have dropped the bomb and they confirmed what we had learned – only the US military has the capability to use JDAMs in Afghanistan.

The weapon fragments said to be found in the rubble from the strike on Masih’s house Via Masih

A close-up of the tail fin with distinctive arrangement of four bolts that indicated it was from a JDAM Via Masih

After four and a half years of recording civilian casualties from strikes in Afghanistan, we were finally able to say for certain who pushed the button on one.

Answering the why

While we believe our investigation answers the who, the why is less clear.

The US’s final statement – that they dropped a bomb on the house after American soldiers reported being fired on – tallies in part with one villager who said the soldiers were shot at from civilian homes. However two others say everything was quiet in the area by the time the strike happened.

Perhaps a clue lies in the location of the house, which was set apart from the rest of the village, very close to a Taliban prison. We know an operation on the prison was carried out, with villagers claiming that a number of security force members being held inside were rescued during the raid. It’s possible that Masih’s house was hit by accident.

This panorama shows how close the two buildings were:

Panorama of the outskirts of Mullah Hafiz, showing the Taliban prison on the left and Masih’s family home on the right Photo sent via Masih

Without full military transparency, these questions will remain unanswered. And whatever the reason for the attack, the US still claims it did not kill any civilians.

Soaring civilian deaths

Our investigation raises serious questions about US military accountability.

Last year, the UN found that US military operations in Afghanistan killed and injured 632 civilians – more than double the year before. The US military has admitted to just over 20 percent of that figure. The reason for the discrepancy, says the US, is that they have access to intelligence such as drone footage which shows that “what often looks like civilian harm from US actions was actually a result of other causes.”

In its first statement back in October, the US spokesperson had warned us: “It isn’t uncommon for insurgents to use these accusations to drive a wedge between the military and the population. As Secretary Mattis has said: ‘We do everything humanly possible consistent with military necessity, taking many chances to avoid civilian casualties at all costs.

“’We’re not perfect guys, but we are the good guys. And so we’re doing what we can.’”

There have been calls for change, even from the Pentagon itself. It released a report in February highlighting concerns about how the US military investigates and responds to civilian casualties. The military was sometimes seen as “restrictive” in how it assessed allegations of civilian harm received from organisations like the Bureau or NGOs, it said.

The report also found that different regional military commands had different processes for reviewing civilian casualties. The US is now developing the first military-wide policy on civilian casualties, which has sparked hopes that things may improve.

For Masih, the pursuit of justice continues. The little money the family managed to save as a result of his work in Iran is now being used for this battle.

“We have a saying; staying silent against injustice is a crime, therefore I will spread my voice throughout the world,” Masih said. “I will talk to everyone, everywhere. I will not stay silent.

“But this is Afghanistan. If someone hears us, or not, we will still raise our voice.”

Additional reporting by Abbie Cheeseman and Ahmed Mengli. This investigation was a partnership between the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and The New York Times’ Visual Investigations team.

To see the video of this story, click here.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

All images in this article are from TBIJ unless otherwise stated