How the Tentacles of the US Military Are Strangling the Planet

In June this year in Itoman, a city in Okinawa prefecture, Japan, a 14-year-old girl named Rinko Sagara read out of a poem based on her great-grandmother’s experience of World War II. Rinko’s great-grandmother reminded her of the cruelty of war. She had seen her friends shot in front of her. It was ugly.

Okinawa, a small island on the edge of southern Japan, saw its share of war from April to June 1945.

“The blue skies were obscured by the iron rain,” wrote Rinko Sagara, channeling the memories of her great-grandmother.

The roar of the bombs overpowered the haunting melody from the sanshin, Okinawa’s snakeskin-covered three-string guitar.

“Cherish each day,” the poem goes, “for our future is just an extension of this moment. Now is our future.”

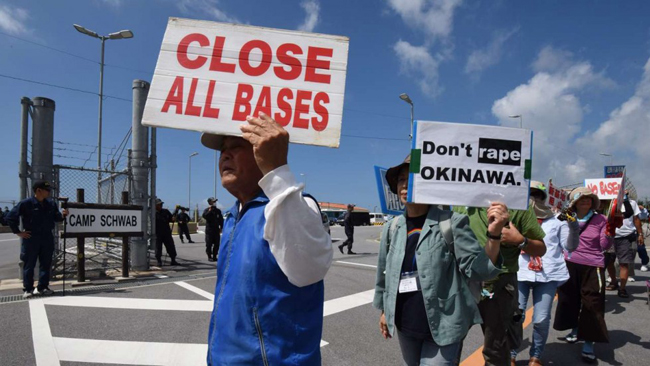

The United States has more than 50,000 troops in Japan as well as a very large contingent of ships and aircraft. Seventy percent of the US bases in Japan are on Okinawa island. Almost everyone in Okinawa wants the US military to go. Rape by American soldiers – including of young children – has long angered the Okinawans. Terrible environmental pollution – including the harsh noise from US military aircraft – rankles people. It was not difficult for Tamaki to run on an anti-US-base platform. It is the most basic demand of his constituents.

But the Japanese government does not accept the democratic views of the Okinawan people. Discrimination against the Okinawans plays a role here, but more fundamentally there is a lack of regard for the wishes of ordinary people when it comes to a US military base.

In 2009, Yukio Hatoyama led the Democratic Party to victory in national elections on a wide-ranging platform that included shifting Japanese foreign policy from its US orientation to a more balanced approach with the rest of Asia. As prime minister, Hatoyama called for the United States and Japan to have a “close and equal” relationship, which meant that Japan would no longer be ordered around by Washington.

The test case for Hatoyama was the relocation of the Futenma Marine Corps Air Base to a less populated section of Okinawa. His party wanted all the US bases to be removed from the island.

Pressure on the Japanese state from Washington was intense. Hatoyama could not deliver on his promise. He resigned his post. It was impossible to go against US military policy and to rebalance Japan’s relationship with the rest of Asia. Japan, but more properly Okinawa, is in effect a US aircraft carrier.

Japan’s prostituted daughter

Hatoyama could not move an agenda at the national level; likewise, local politicians and activists have struggled to move an agenda in Okinawa. Tamaki’s predecessor Takeshi Onaga – who died in August – could not get rid of the US bases in Okinawa.

Yamashiro Hiroji, head of the Okinawa Peace Action Center, and his comrades regularly protest against the bases and in particular the transfer of the Futenma base. In October 2016, Hiroji was arrested when he cut a barbed-wire fence at the base. He was held in prison for five months and not allowed to see his family. In June 2017, Hiroji went before the United Nations Human Rights Council to say,

“The government of Japan dispatched a large police force in Okinawa to oppress and violently remove civilians.”

Protest is illegal. The Japanese forces are acting here on behalf of the US government.

Suzuyo Takazato, head of the organization Okinawa Women Act Against Military Violence, has called Okinawa “Japan’s prostituted daughter.” This is a stark characterization. Takazato’s group was formed in 1995 as part of the protest against the rape of a 12-year-old girl by three US servicemen based in Okinawa.

For decades now, Okinawans have complained about the creation of enclaves of their island that operate as places for the recreation of American soldiers. Photographer Mao Ishikawa has portrayed these places, the segregated bars where only US soldiers are allowed to go and meet Okinawan women (her book Red Flower: The Women of Okinawa collects many of these pictures from the 1970s).

There have been at least 120 reported rapes since 1972, the “tip of the iceberg,” says Takazato. Every year there is at least one incident that captures the imagination of the people – a terrible act of violence, a rape or a murder.

What the people want is for the bases to close, since they see the bases as the reason for these acts of violence. It is not enough to call for justice after the incidents; it is necessary, they say, to remove the cause of the incidents.

The Futenma base is to be relocated to Henoko in Nago City, Okinawa. A referendum in 1997 allowed the residents of Nago to vote against a base. A massive demonstration in 2004 reiterated their view, and it was this demonstration that halted construction of the new base in 2005.

Susumu Inamine, former mayor of Nago, is opposed to the construction of any base in his city; he lost a re-election bid this year to Taketoyo Toguchi, who did not raise the base issue, by a slim margin. Everyone knows that if there were a new referendum in Nago over a base, it would be roundly defeated. But democracy is meaningless when it comes to the US military base.

Fort Trump

The US military has a staggering 883 military bases in 183 countries. In contrast, Russia has 10 such bases – eight of them in the former USSR. China has one overseas military base. There is no country with a military footprint that replicates that of the United States. The bases in Japan are only a small part of the massive infrastructure that allows the US military to be hours away from armed action against any part of the planet.

There is no proposal to downsize the US military footprint. In fact, there are only plans to increase it. The United States has long sought to build a base in Poland, whose government now courts the White House with the proposal that it be named “Fort Trump.”

Currently, there are US-NATO military bases in Germany, Hungary and Bulgaria, with US-NATO troops deployments in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The United States has increased its military presence in the Black Sea and in the Baltic Sea.

Attempts to deny Russia access to its only two warm-water ports in Sevastopol, Crimea, and Latakia, Syria, pushed Moscow to defend them with military interventions. A US base in Poland, on the doorstep of Belarus, would rattle the Russians as much as they were rattled by Ukraine’s pledge to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and by the war in Syria.

These US-NATO bases provide instability and insecurity rather than peace. Tensions abound around them. Threats emanate from their presence.

A world without bases

In mid-November in Dublin, a coalition of organizations from around the world will hold the First International Conference Against US/NATO Military Bases. This conference is part of the newly formed Global Campaign Against US/NATO Military Bases.

Source: Global Campaign Against US/NATO Military Bases

The view of the organizers is that “none of us can stop this madness alone.” By “madness,” they refer to the belligerence of the bases and the wars that come as a result of them.

A decade ago, a US Central Intelligence Agency operative offered me the old chestnut, “If you have a hammer, then everything looks like a nail.” What this means is that the expansion of the US military – and its covert infrastructure – provides the incentive for the US political leadership to treat every conflict as a potential war. Diplomacy goes out of the window. Regional structures to manage conflict – such as the African Union and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization – are disregarded. The US hammer comes down hard on nails from one end of Asia to the other end of the Americas.

The poem by Rinko Sagara ends with an evocative line: “Now is our future.” But it is, sadly, not so. The future will need to be produced – a future that disentangles the massive global infrastructure of war erected by the United States and NATO.

It is to be hoped that the future will be made in Dublin and not in Warsaw; in Okinawa and not in Washington.

This article was produced by Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute, which provided it to Asia Times.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute. He is the chief editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.