Capitalizing on Conflict: How Defense Contractors and Foreign Nations Lobby for Arms Sales

All Global Research articles can be read in 27 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

***

Defense companies spend millions every year lobbying politicians and donating to their campaigns. In the past two decades, their extensive network of lobbyists and donors have directed $285 million in campaign contributions and $2.5 billion in lobbying spending to influence defense policy. To further these goals they hired more than 200 lobbyists who have worked in the same government that regulates and decides funding for the industry.

Defense companies sell a variety of products and services around the world from missiles, rifles and personnel equipment to tanks, aircraft and complex electrical and computer systems. The industry’s political activity is dominated by the well known behemoths. Just 200 defense companies reported lobbying the federal government in 2020. The top five account for more than 50 percent of the industry’s lobbying and the top 15 spend 75 percent of the lobbying money. The five biggest spenders in 2020 — Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, Raytheon Technologies and General Dynamics — spent $60 million altogether.

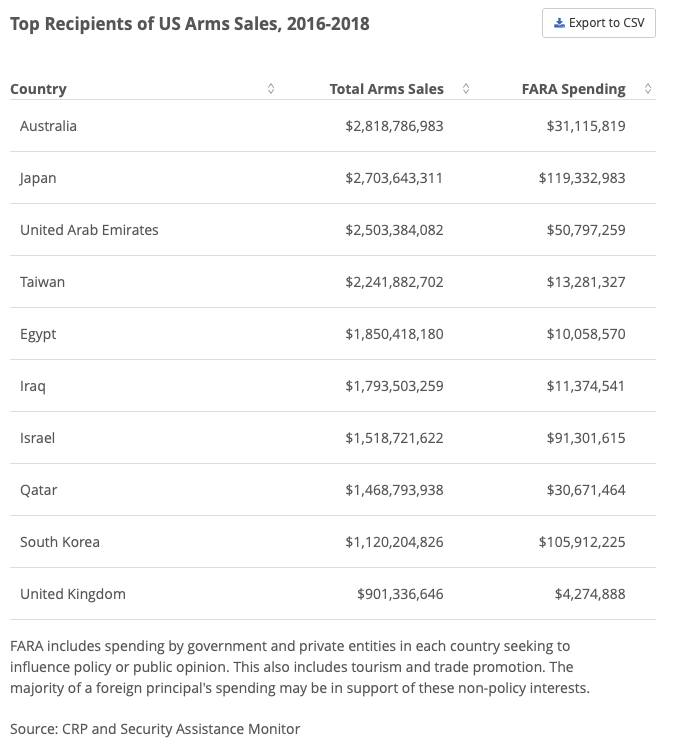

The defense industry’s business prospects are tightly controlled and in many ways entirely decided by official decisions made in Congress and the Pentagon in a way that other industries don’t have to contend with. Despite those restrictions, business is undeniably good both at home and abroad. Foreign sales delivered an average of $12 billion worth of arms per year between 2016 and 2018, according to Security Assistance Monitor data analyzed by the Center for Responsive Politics.

That’s on top of a sizable portion of the $740 billion Pentagon budget spent on weapons for use by the U.S. military. When it comes time for Congress to decide funding levels for a Pentagon that spends nearly three times as much as any other military in the world, arms manufacturers and military support sellers have an extensive network of lobbyists and former government employees pushing their business interests to members of Congress who have taken contributions from them and also often have constituents employed by them.

While it is well known that the U.S. spends enormous sums to keep the most powerful military in history humming, many may be unaware that a major part of the industry’s business model is selling arms to other countries with the blessing of the U.S. Congress and State Department. Often those arms are developed using taxpayer money. Over the last year, American defense firms struck deals to sell $175 billion worth of weapons, including $23 billion worth of F35 fighters and drones to the United Arab Emirates, and multi-billion dollar sales to Taiwan and Saudi Arabia.

These deals are sometimes controversial. The Senate tried — and failed — to block the Trump administration backed sales to the UAE and Saudi Arabia amid concerns about their use in Yemen as well as worries about human rights abuses such as the killing of Jamal Khashoggi, a Washington Post journalist and U.S. green card holder critical of the Saudi government. The presidential election did what the Senate could not, and within weeks of taking office, President Joe Biden paused those sales for review. With Democrats in charge of the Senate, Robert Menendez (D-N.J.) and Jack Reed (D-R.I.), both instrumental in the effort to block the deals, now chair the Foreign Relations and Armed Services committees respectively.

Despite the suspensions, new sales agreements continue. Since Biden’s inauguration, the State Department approved an $85 million sale of Raytheon manufactured missiles to Chile and $60 million worth of Lockheed Martin’s F-16 aircraft and services to Jordan.

While Biden has touted strict ethics rules that attempt to thwart the influence of lobbyists on the administration, several of his earliest appointees, including Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin and Secretary of State Antony Blinken consulted for a private equity firm that emphasized its “access, network and expertise” in the defense industry. Austin also had a seat on the United Technologies and Raytheon board, earning more than $250,000 from the now merged companies. Raytheon CEO Greg Hayes seems optimistic about the company’s prospects under the new administration, telling investors in January that “peace is not going to break out in the Middle East anytime soon” and that the region “remains an area where we’ll continue to see solid growth.”

Playing both sides

Both customers and suppliers are putting the squeeze on the U.S. government to continue the flow of arms. Some of the biggest foreign consumers of U.S. arms are also spending considerable sums to exert their influence in the U.S., though some of the biggest spenders, including South Korea and Japan, are focused on trade and commercial issues rather than military matters, according to disclosures.

Since 2017, Saudi Arabia has become the second biggest buyer of U.S. arms, with $26 billion worth of sales reported to Congress so far. At the same time, the Saudi government and state owned enterprises like SABIC reported spending $108 million since 2016 on their U.S. influence operation, the sixth most of any country in the world. They hired prestigious firms such as Brownstein Hyatt, Squire Patton Boggs and the BGR Group. Those firms are also top lobbyists for domestic clients, including defense companies.

Saudi Arabia also benefits from the influence wielded by major U.S. arms manufacturers that would like to sell to them. Just four of the biggest companies received 90 percent of promised sales between 2009 and 2019, according to the Center for International Policy. Those four — Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, General Dynamics and Boeing — also happen to make up four of the top five defense-related companies spending the most on lobbying, pouring over $10 million each into their policy influence efforts in 2020 alone.

In fact, some defense industry lobbyists are also registered foreign agents on behalf of the very same countries that are angling to buy U.S. arms.

Squire Patton Boggs

Squire Patton Boggs, a perennial K Street powerhouse, represented Saudi Arabia during 2017 for $750,000, the year the country first signed a monumental $110 billion dollar U.S. arms deal. In the preceding and following years, they would represent two of the major beneficiaries of those sales, Raytheon and Northrop Grumman.

Akin Gump

In 2018 UAE bought $270 million worth of Raytheon Sidewinder missiles. Meanwhile, Akin Gump has represented UAE since 2007, working on a myriad of issues including defense policy and the Arms Export Control Act originally and currently covering “withdrawal from the war in Yemen, export controls and possible arms sales.” With the 2020 merger of United Technologies — an Akin Gump client since late 2008 — and Raytheon, Akin Gump now represents both Raytheon and the UAE. Among the sales under review by the Biden administration are a $10 billion sale to UAE, partially consisting of Raytheon missiles and munitions.

American Defense International

The aptly named American Defense International specializes in lobbying and consulting on defense matters and made $3.9 million in 2020 representing clients that nearly all have business with the Pentagon.

Among ADI’s clients are well-known defense manufacturers such as General Dynamics, Raytheon and L3Harris. But over the last 10 years, ADI’s biggest client has been General Atomics, a leading manufacturer of drone systems and major beneficiary of the Trump administration’s decision to loosen restrictions on selling drones abroad. Among the sales to the United Arab Emirates currently under review is $3 billion worth of General Atomics made SkyGuardian drones and equipment.

At the same time, they also represent one of the biggest buyers of U.S. arms. Starting in 2018, ADI began representing the UAE for work on “legislative and related policy matters” on the topics of “engagement in Yemen, military sales from the United States and relationship with the United States.” Soon after, ADI began lobbying to unfreeze weapons sales to the UAE — a move that could potentially benefit weapons manufacturers and foreign clients alike.

The Foreign Agents Registration Act requires foreign entities such as foreign governments and political parties to report their U.S. influence efforts to the Department of Justice. But U.S. based organizations and most companies report a more limited set of activities under the Lobbying Disclosure Act.

Spending millions to make billions

The defense industry spent $216 million directly lobbying the federal government since the start of 2019. While other industries spend far more on lobbying — the pharmaceutical industry spent almost $306 million in 2019 alone — the military budget continues to dominate the country’s discretionary spending and American weapons producers export more arms abroad than any other country.

As of 2019, the most recent year for which arms data is available, American companies make up the top five arms sellers globally and export to nearly 100 countries in every region of the world according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Meanwhile, those five companies spent $54.6 million lobbying Congress and the executive branch that same year.

Depending on the type of transaction, overseas arms sales are approved by the Foreign Affairs committees and the State Department’s Arms Sales and Defense Trade office, specifically the Bureau of Political Military Affairs.

While few companies report lobbying the relatively obscure State Department office that approves arms sales, Raytheon does consistently report lobbying the Defense Security Cooperation Agency, a Pentagon office that administers sales approved by the State Department, on “Congressional notifications of proposed foreign military and direct commercial sales.” Among the five defense companies that spend the most on lobbying, all but one lobbied the State Department in 2020. General Dynamics, Northrop Grumman and Raytheon reported lobbying State Department officials specifically about foreign military sales. Lockheed Martin also reported contacting the State Department.

Revolving door keeps defense contractors connected

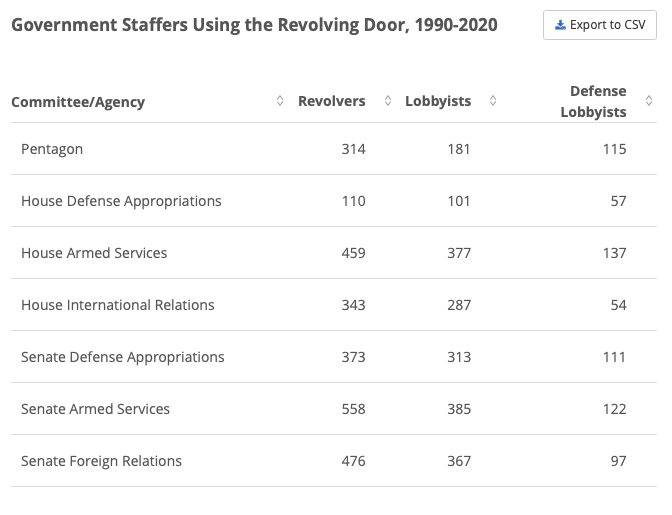

In addition to spending millions, the defense industry makes use of one of the most well-connected lobbying corps in Washington, D.C. Seventy-three percent of the 663 lobbyists employed by defense companies in 2020 formerly worked for the federal government. These connections make for cozy relationships and highly useful contact lists. Overworked and underpaid congressional staffers can also hope that lucrative lobbying jobs await them at the same companies who come to them pushing their own agendas. No other sector has a higher percentage of lobbyists who also worked in the government.

A similarly cozy relationship exists between the industry and the Defense Department. In a 2018 report informed by the OpenSecrets revolving door database, the Project on Government Oversight found that 95 former Pentagon officials went through the revolving door to represent just the top five defense contractors in 2016. Our original research similarly finds hundreds of defense industry lobbyists with Defense Department backgrounds. Common career paths also take people through Congress, think tanks and defense companies with significant connections to decisions made in the Pentagon.

But the relationship between the industry and the Pentagon is only part of the story. The House and Senate Armed Services and Foreign Relations committees and the Defense Appropriations subcommittees examined here have seen at least 250 people pass through on their way to the private sector or vice versa in the last 30 years, a quarter of whom were officially registered lobbyists for defense companies or trade groups. Even more striking are the numbers for the staff of committee members. Nearly 530 people have worked for both a member of one of the six main defense related committees and as a lobbyist for defense companies. Some staffers straddle both groups, working for both the committee and a member of the committee, not infrequently at the same time.

On balance, a third of revolvers identified by CRP as working for these committees and their members also have been a registered lobbyist representing defense companies.

Lester Munson, BGR Group

Among them is Lester Munson, a principal at BGR Group who represents a number of international and defense clients including Raytheon, Chevron and the government of Azerbaijan. Munson spent nearly two decades working on international relations issues on Capitol Hill in addition to a stint at USAID. Most recently, he served under former Chairman Bob Corker for the Senate Foreign Relations committee.

Mark Esper, Former Secretary of Defense

Former Secretary of Defense Mark Esper, spent the late ’90s and early 2000s working his way through the Senate Foreign Relations and House Armed Services committees in addition to a couple of years as an assistant deputy secretary of defense. After spending seven years in the government relations office of Raytheon, he was tapped by President Trump as Secretary of the Army and ultimately headed up the Pentagon.

John Bonsell, SAIC

The last decade has seen John Bonsell spinning through the revolving door repeatedly between managing staffing at the Senate Armed Services committee, advising chairman James Inhofe (R-Okla.) and lobbying on behalf of defense industry powerhouse SAIC. Prior to 2013, he spent five years as head lobbyist at Robison International representing BAE Systems, Boeing and SAIC. Over the next nine years, he sandwiched government relations work at SAIC between two stints at the Armed Services Committee. He rejoined SAIC this month after Democrats took over the majority on the committee.

Jeff Bozman, Armed Services Committee

After serving as a Marine officer, Jeff Bozman spent seven years at Covington & Burling representing defense giants Northrop Grumman, BAE Systems and Bombardier as a specialist in government contracts and national security. In 2020, Bozman joined the House Armed Services staff to serve as counsel to committee Chairman Adam Smith (D-Wash.)

Bob Simmons, Boeing

Bob Simmons spent 12 years as staff director of the House Armed Services Committee, managing strategic planning for one of the largest committees in Congress before moving to Boeing, where he is now a vice president of government operations. He was succeeded at the time by his deputy, Jenness Simler, but not for long — she joined him at Boeing less than six months later.

Maria Bowie, Leidos

For 10 years, Maria Bowie served as deputy chief of staff for Rep. Tom Cole (R-Okla.). In February 2021, she became the director of government affairs at Leidos, a leading software and IT defense contractor. She was a lobbyist for BAE Systems between 2001 and 2003.

Justin Brower, JA Green & Co

After working for Rep. Dutch Ruppersberger (D-Md.) as a military advisor as well as for the House defense subcommittee on which he sits, Justin Brower left in 2019 and promptly registered to lobby on behalf of Raytheon Technologies and German-owned munitions manufacturer American Rheinmetall.

Defense contractors invest in congressional committees

Lobby reports don’t provide enough detail to know which members were pressed by defense industry lobbyists, but we do know whose campaigns the companies funded. The defense sector is expert at targeting members of committees that more or less directly decide their income levels. Over the last 20 years defense PACs and employees poured $135 million into the campaign coffers and leadership PACs of members who sit on the key committees that oversee them. That accounts for 60 percent of the total money they gave to all members of Congress even though these key politicians made up only 43 percent of the members the industry supported. In other words, Six in 10 dollars went to just 4 in 10 politicians.

While the defense industry clearly favors key committee members, they still cast a wide net, giving an additional $92 million since 2001 to members of Congress who did not sit on those committees. Still, the average member of Congress got $179,000 in campaign contributions from defense companies during that period while members of the committees averaged $250,000.

House Armed Services members attracted more than twice as much money as the other committees at $54 million in campaign support. The committee is responsible for the Pentagon’s main funding vehicle, the National Defense Authorization Act, which also happens to be one of the most lobbied bills of each cycle. In 2020, more than 730 organizations enlisted 1,633 lobbyists to press their case regarding the $740 billion funding bill and among the most active were General Dynamics, Lockheed Martin and Raytheon Technologies.

Among the top defense contribution recipients over the last 20 years, the last three chairmen of House Armed Services are all represented in the top eight. Current Chairman Adam Smith (D-Wash.) raised $1.9 million while a member of the committee and predecessors Buck McKeon (R-Calif.) and Mac Thornberry (R-Texas) raised $1.8 million and $2.1 million respectively. McKeon is now a lobbyist working on behalf of both Saudi Arabia and major defense contractors.

Only Sen. Richard Shelby (R-Ala.), who chaired the powerful Appropriations Committee and its defense subcommittee for the last three years, outraised Thornberry, raking in over $3.5 million since 2001. Shelby recently announced he would not run for reelection in 2022 after a four-decade career in Congress.

Contributions to the members of most defense-related committees from the industries they fund and regulate tend to favor Republicans — with 54 percent going to fund GOP candidates and their leadership PACs — but there is no reluctance to fund key allies in Congress. Six of the top 10 recipients of defense money are Democrats, several of them having served on the defense appropriations subcommittee. Among those are Reps. John Murtha (D-Penn.), Jim Moran (D-Va.) and Pete Visclosky (D-Ind.), all one-time members of the House Defense Appropriations subcommittee and all of whom raised more than $1.9 million.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

A previous version of this report incorrectly attributed lobbying by Buck McKeon on behalf of Saudi Arabia and defense contractors to Mac Thornberry.

A previous version of this report stated the U.S. planned to deliver $450 billion in weapons to Saudi Arabia. While Trump cited that figure numerous times, the verifiable total so far is $26 billion.

Karl Evers-Hillstrom contributed to this report.

Featured image is from NationofChange