Homophobia and Misogyny in America: The Origins of Second Wave Feminism

The Story of Lesbian Feminism Part 1

Author’s Note: Please note that this is only an examination of the origins and difficulties between second wave and lesbian feminism. I understand as a male that I will never fully grasp what it means to live as an American woman, particularly a lesbian, in a society plagued with homophobia and misogyny. Any critiques that are made in the following article is purely from an intellectual standpoint and not a criticism of women, the women’s movement, or the lesbian feminist movement.

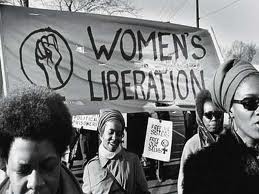

Feminism is a word that conjures up images of pro-choice marches, bra-burnings, and angry women. Often being misunderstood, feminism has been distorted by the mainstream society to mean that such women have a hatred of men, often being called “feminazis.” While such a view only contributes to the oppression of women in American society and socializes the young to think that it is alright to treat women in a disrespectful manner, there were and are also problems within the feminist movement itself, with feminists oppressing others whom, one would think that logically, they should embrace.

Historically speaking one learns very little about feminism and only then within the context of the first wave of the feminist movement, women’s suffrage. This ignores what is arguably the most influential and important feminist movement that is the reason for so much of the strides women have made- the second feminist movement, more commonly known as the Women’s Liberation Movement. However, even here there is still much unacknowledged history that hasn’t much gotten into the mainstream, specifically that of lesbian feminism and the up and downs that that movement had with the liberal feminists. Lesbian feminism forced the liberal feminist movement to confront its own homophobia and changed the face of feminism itself.

The Origins of Second Wave Feminism

In order to understand the foundations of lesbian feminism and its effects, there must first be an understanding of the origins of the Women’s Liberation Movement. Ironically enough, the feminist movement found its true start not with a woman, but with both a man and a woman.

Originally there was no care of the plight of women in society as America more or less revolved around the patriarchal race and class-based system that favored straight white middle and upper-class males. However, this began to change with the election of John F. Kennedy in 1961. Originally, he “brought to his cabinet and to his inner advisory circles other young and (he thought) brilliant men”[1] calling them the “New Frontiersmen.” Incensed at this, Eleanor Roosevelt reportedly challenged Kennedy by posing the question “Where are the women on your New Frontier?” In order to amend the situation and seeing as how Eleanor had been such an influence in getting him elected, Kennedy agreed to establish a commission to inquire as to the situation of women in the US, with Roosevelt as chair.

The women on the commission were those in their forties and fifties who were professionals in fields such as economics and law and as such, highly educated and well off. Overall, they were unconcerned with giving women equal rights and more concerned with “combating the disabilities women suffered as a corollary of their sex, disabilities such as abandonment and poverty.”[2] The very nature of the commission was not to be revolutionary, as the people that staffed it were not revolutionaries but rather those who wanted so slightly reform the status quo and thus the cards in the deck would be reshuffled, but no radical changes would be made to give women full equality.

The commission’s first task was to become fully informed about the situation of women in the country which was quite difficult seeing as how only the Department of Labor had any information concerning women and even then women’s employment and pay records were compared only to other women and “the cost of sex discrimination in employment, as in professional entry quotas, [had] never [been] calculated.”[3] Thus, there was much ground work to cover.

By 1963, the commission presented their findings to the President. The commission recommended that “the president appoint a permanent citizens’ advisory council on the status of women and that states create comparable commissions to continue the work.”[4] Thus, rather than disbanding, the commission was created on the state level and the findings of each state complied and finally bought back to Washington in 1966. This resulted in Title 7 of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which states that discrimination based on one’s sex was illegal. Yet, interestingly enough, Title 7 only came about due to what one might call an accident.

There was a large amount of disagreement over the creation of the equal opportunity employment based on race. One Congressional Representative, Howard W. Smith, introduced sex as a protected category as a way to “demonstrate the ‘ludicrousness’ of the whole idea of applying equal rights to jobs.”[5] This would on him as the thirteen women in the House of Representatives and one Senator, Margaret Chase Smith, saw Smith’s joke as “an opportunity to write a prohibition of gender discrimination in employment into the act.”[6]

But even with some senators supporting the amendment, others were against it as in their minds the Civil Rights Act was specifically for African-Americans, thus women should not be included in the bill. Yet the case was made that employers would possibly hire black women over white women in order to avoid charges of racial discrimination, thus the amendment should be passed. It is important to note the use of race in this argument, with the amendment being viewed as a way to ensure that black women didn’t get economically ahead of their white counterparts and that employment would be secured for white women.

To enforce Title 7, Congress established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to hold public hearings on what regulations should be made, conduct investigations, and then to enforce the new law. One issue of the EEOC that was important to women was sex-differentiated want ads. From the point of view of women, such ads not only reinforced existing discrimination, but also “lowered [the] expectations [of women] and contributed to female socialization.”[7] However, the head of the EEOC, Franklin Delano Roosevelt Jr. was not interested in such issues nor was a resolution that demanded across the board enforcement of Title 7 allowed to be introduced to Congress thus allowing sex-differentiated ads to continue.

It was at this moment, this mixture of success, anger, and hope that allowed for second wave feminism to be born. During the national conference on Title 7, Betty Friedan and 15 other women met and decided to push state representatives to enforce Title 7 and reappoint Richard Graham as head of the EEOC, the only male commissioner that could actually be called a feminist. When the resolution was refused to even be introduced, women who had met with Friedan began to discuss taking action outside of the legislative system. “Days later, thirty woman and men gathered to officially found the National Organization for Women” in order to “press government from the outside to better enforce the regulations that were on the books.”[8] Yet, this united group of feminists would not stand together long as there were those feminists who would see NOW as not going far enough and break off to form new strands of feminism.

Second Wave Feminist Theory

Second Wave Feminist Theory finds its roots, for the most part in Betty Friedan’s The Feminist Mystique in which she analyzes the oppression of women, specifically that of housewives in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Friedan initially states that the problem women have is that of the feminine mystique which came about due, in part, to people such as Marynia F. Farnham and Ferdinand Lundberg. In their book Modern Woman: The Lost Sex, they argue for what is effectively the suppression of women and that they would be much better off in the home. Farnham and Lundberg stated in the book that it was more and more common for women to attempt to combine work with childrearing and “When these two spheres are combined it is inevitable that one or the other will become of secondary concern and, this being the case, it is certain that the home will take that position.”[9]

In doing this, the authors are stating that the woman’s natural place is the home and reduces women to the stereotypical position of nurturer and caretaker that has been placed upon them. The views of Farnham and Lundberg are extremely conservative. When discussing women having to balance their careers and home lives, they express misgivings about such an occurrence, professing that such circumstances create “a situation that is by no means as smoothly functioning nor so satisfying either to the child or the woman.

She must of necessity be deeply in conflict and only partially satisfied in either direction. Her work develops aggressiveness, which is essentially a denial of her femininity, an enhancement of her girlhood-induced masculine tendencies.”[10] (emphasis added) Stating that a woman’s aggressiveness was a denial of a woman’s femininity is not only a definition of femininity from a male perspective, but it also restricts women to the role of domesticity and in doing so puts them at the mercy of men.

They blatantly put themselves against women gaining independence stating that “it is imperative that these strivings be at a minimum and that her femininity be available both for her own satisfaction and for the satisfaction of her children and husband”[11] and that

As the rivals of men, women must, and insensibly do, develop the characteristics of aggression, dominance, independence and power. These are qualities which insure success as coequals in the world of business, industry and the professions. The distortion of character under pressure of modern attitudes and upbringing is driving women steadily deeper into personal conflict soluble only by psychotherapy. For their need to achieve and accomplish doesn’t lessen in anyway their deeper need to find satisfactions profoundly feminine. Much as they consciously seek those gratifications of love, sensual release and even motherhood, they are becoming progressively less able unconsciously to accept or achieve them. [12]

This is an open argument that women should dedicate themselves to the home and the family, damning them to a life of morbidity.

Finally, the two later affirm that a woman with a career is dangerous as it is contrary to them “supporting and encouraging [their husband’s] manliness and wishes for domination and power.”[13] Within all of this was a manner of thinking that espouses that women only exist to be used by men and for men and argues for the complete and total control of women within a totalitarian subculture that is the household.

The true ideology that Farnham and Lundberg advocate is one that effectively dehumanizes woman. By stating arguments that women must keep their own desires for independence “to a minimum” and that their “femininity be available both for [their] own satisfaction and for the satisfaction of her children and husband,” both are showing not only what they personally think of women, but are showing that they think women are naturally lesser than men and nothing but a tool to be used for and by men.

It was among this atmosphere of objectifying and oppressing women that permeated every facet of American culture and created a misogyny that a new wave of feminism was needed to express that women were in fact human beings rather than just robots that existed solely for to pleasure and care for men and have children.

To fill in this void and combat the patriarchal structure that oppressed women, Betty Friedan wrote The Feminine Mystique that sparked off the entire second wave of feminism. In the book, Friedan advocates for the economic independence of women, stating that “for women to have full identity and freedom, they must have economic independence” and “Only economic independence can free a woman to marry for love, not for status or financial support, or to leave a loveless, intolerable, humiliating marriage, or to eat, dress, rest, and move if she plans not to marry.”[14]

In advocating for the economic independence of women, Friedan is advocating a situation in which women will be able to take the first step to becoming fully independent of the patriarchal system. However, this is made all the more revolutionary when one realizes the fact that economics and politics go hand-in-hand. By arguing for economic independence, Freidan is setting the stage for eventual political independence and self-determination that can be asserted by women in America.

Friedan takes on this view of femininity which only encourages the subjugation of women. She writes that according to the feminine mystique the problem is in the past women “envied men, women tried to be like men, instead of accepting their own nature, which can find fulfillment only in sexual passivity, male domination, and nurturing maternal love.”[15] Yet, she realizes the horror of such an existence and expounds upon it.

In the twelfth chapter, Progressive Dehumanization: The Comfortable Concentration Camp, Friedan compares the situation that women found themselves into being in a concentration camp. She wrote “In fact, there is an uncanny, uncomfortable insight into why a woman can so easily lose her sense of self as a housewife in certain psychological observations made of the behavior of prisoners in Nazi concentration camps.”[16] After going into the effects that concentration camps had on prisoners such as the adoption of childlike behavior, being cut off from pasts interests, and “the world of the camp [being] the only reality,”[17] Friedan then argues that the 1950s American woman finds herself in a very similar situation.

All this seems terribly remote from the easy life of the American suburban housewife. But is her house in reality a comfortable concentration camp? Have not women who live in the image of the feminine mystique trapped themselves within the narrow walls of their homes? They have learned to ‘adjust’ to their biological role. They have become dependent, passive, childlike; they have given up their adult frame of reference to live at the lower human level of food and things. The work they do does not require adult capabilities; it is endless, monotonous, unrewarding. American women are not, of course, being readied for mass extermination, but they are suffering a slow death of mind and spirit.[18] (emphasis added)

Her comparison is, without a doubt, quite extreme. The situation of the suburban housewife, while lamentable and in extreme need of improvement is not in any way near that of the suffering of a Holocaust victim. Yet, she was using this extreme hyperbole to make the point that women are slowly suffering in their home lives.

While Friedan is much regarded as a major figure in the feminist movement, she does have her detractors that make legitimate critiques of her analysis. Most notedly, Friedan was critiquted for the mass amount of exclusivity in her analysis. The sole focus of her book was white middle-class suburban housewives and because of such a biased analysis, “the problems facing, for example, millions of poor, working women or non- white women — oppressive working conditions and low pay, racism, and the burdens of a double day — barely register on the radar screen of The Feminine Mystique.”[19] By focusing on a specific group of women, Friedan somewhat lowers the value of her analysis.

Friedan’s class bias affects her analysis of the situation that women, no matter what socioeconomic class they were in, generally found themselves in at the time of her writing. Such a view reveals a problem with liberal feminism as it centers “on its seemingly bland acceptance of American capitalism as a system structured on economic freedom which merely needs some tinkering (such as the elimination of ‘unfair practices’ such as racism and sexism) to make it entirely workable and just.”[20] In doing this, liberal feminism loses its potential for true revolutionary change as it advocates what simply adds up to reforms to the system which allows the overall oppression of groups, including women, and the patriarchy to continue rather than creating a new system that sought the equality of all people.

Yet, many women on the Left would find that the feminism that Friedan and NOW espoused was not for them and could not work for their given situation. On the Left the marginalizations of women wasn’t concerned with the getting equal access to jobs, but were much more concerned with getting respect and addressing women’s oppression that existed from the so-called inclusive Left.

Notes

[1] Sheila Tobias, Faces of Feminism: An Activist’s Reflections On The Women’s Movement (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1997), pg 73

[2] Tobias, pg 74

[3] Tobias, pg 74

[4] Tobias, pg 75

[5] Tobias, pg 81

[6] Tobias, pg 81

[7] Tobias, pg 83

[8] Tobias, pg 85

[9] Marynia F. Farnham, Ferdinand Lundberg, Modern Woman: The Lost Sex, http://web.viu.ca/davies/H323Vietnam/The_Lost_Sex.1947.htm

[10] http://web.viu.ca/davies/H323Vietnam/The_Lost_Sex.1947.htm

[11] http://web.viu.ca/davies/H323Vietnam/The_Lost_Sex.1947.htm

[12] http://web.viu.ca/davies/H323Vietnam/The_Lost_Sex.1947.htm

[13] http://web.viu.ca/davies/H323Vietnam/The_Lost_Sex.1947.htm

[14] Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique (New York: Dell Book, 1963), pgs 370-71

[15] Friedan, pg 43

[16] Friedan, pg 305

[17] Friedan, pg 306

[18] Friedan, pgs 307-308

[19] Joanne Boucher, Betty Friedan and the Radical Past of Liberal Feminism, New Politics 9:3 (Summer 2003), http://nova.wpunj.edu/newpolitics/issue35/boucher35.htm

[20] http://nova.wpunj.edu/newpolitics/issue35/boucher35.htm