Hollywood’s Crusade against Muslims, Film Portrayal of Arabs. The Writings of Media Critic Jack Shaheen

Featured image: Jack Shaheen (Source: NPR)

The event of 9/11 is unparalleled in history, in drama, in audacity, in the terrorific images, in deaths, in its live transmission, in its ongoing controversies. It remains a traumatizing American experience with continually unfolding consequences. One result is the rise and persistence of hostility by Americans not only towards the [alleged] perpetrators, Arab agents purportedly motivated by a religious ideologue, but also entire Arab nations and Arab and Muslim peoples worldwide.

This everlasting bitterness exaggerates the tragedy in the minds of Americans. At the same time, it interrupts and distorts Muslims’ self-identity and the daily injustices we experience.

Any conversation, private or public, with other Muslims about our current woes and anxieties– our prayers and dreams, our relations with fellow students, neighbors and co-workers– somehow finds its way back to that dreadful iconic date in 2001. It is a shadow haunting us wherever we go—to the ballot box, in our classroom, at a job interview, down our neighborhood street, on a holiday.

That event has become such a part of us, even if we think we buried it, that we unwittingly own it. We write books and magazine essays condemning terror and demonstrating our American-ness; we pen memoirs documenting our victimization; we reply to surveys testifying to our children’s bullying by classmates and teachers alike; we join interfaith sessions; we seek out grants to teach others about the calm nature of our religion and the beauty of our cultures. Even as we do so, that awful event remains the peg around which our existence rotates—favorably or otherwise.

The death of media critic Jack Shaheen earlier this month is an opportunity to offer our post-9/11 generation (there it is again) of activists and commentators an essential historical perspective on the demonizing process in which we are enmeshed.

Shaheen’s work needs to be better known by American Muslims. It warns us:

“Go beyond 9/11; that vicious blight consuming our history and humanity has been with us for a long time. It’s not only driven by our nightly news broadcasts; it is embedded in our children’s school books and our most entertaining action films starring our favorite actors”.

As powerful as the medieval Christian crusade, Hollywood’s film industry is behind a century of productions targeting Arab and Muslim peoples—in animated children’s films, exotic tales of romance, and in American war legends.

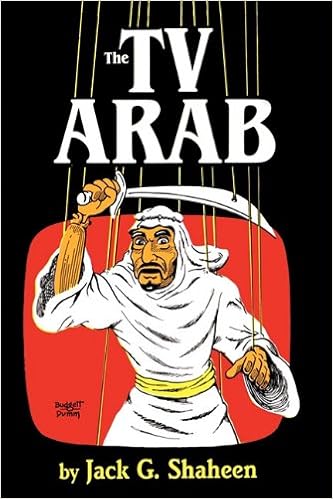

Shaheen was a professor of communications who focused his attention as a media critic on film portrayals of Arabs; his exhaustive work provides irrefutable documentation of the creation of the “bad arab” in cinema and lore. He expanded his arguments, first published in TV Arab (1984), in his later book, Reel Bad Arabs (2001 and 2012), offering hundreds of examples of the mindless belly dancer, the veiled seductress, the sword-wielding assassin, the hook-nosed desert nomad, the oil-rich despot. You know them well.

Since the early days of the silent cinema those images remain popular in today’s biggest Hollywood blockbusters. The terrifying Arab was ultimately given a tangible personality in the form of the PLO (Palestinian Liberation Organization). As noted by Rima Najjar writing about the political manipulation of this concept “The pattern of dehumanizing Palestinian Arabs and/or deliberately obscuring their humanity are factors that have facilitated Israel’s project of designating Palestinian resistance movements as terror organizations.”

Although the PLO was distinctly secular and socialist, by the 1980s their image became layered with a religious identity conveniently found in the Gaza-based movement Hamas. As Hamas gained recognition as the image of Palestinian resistance, the threat to Israel was now ‘Islamic terror’.

In 1984 came the highly successful autobiography Not Without My Daughter which in 1991 was made into a popular film of the same name starring Sally Fields. Its promotional blurb sums up the storyline thus: “An American woman, trapped in Islamic Iran by her brutish husband, must find a way to escape with her daughter…”. Septembers of Shiraz, a 2015 film I plucked at random from my local library only yesterday, assures continuation of filmic exploitation of a ‘revolutionary Iran’ and Islam, and the racist values they perpetuate. We are reminded of our media’s role in this process with a recent admission by the New York Times.

The course by which Islam became such a fearsome concept, effectively manipulated for political purposes primarily through American media is best documented by the outstanding culture critic Edward Said in his 1981 Covering Islam. Even today, with our abundance of so-called experts on Islam, from gadflies to published professors, Covering Islam remains unsurpassed as an analysis of the role of our media in designing a frightening ogre for American consumption, a creation that daily deepens mistrust among peoples and shapes foreign policy. Nothing I have read in these decades of overwhelming attention on Islam supersedes Said’s brilliant, straightforward analysis. Along with Mahmood Mamdani’s Good Muslim, Bad Muslim, it ought to be read and used by every journalism student, every political scientist, every anthropologist, and every Muslim.

Shaheen’s exposé on the role of film in fostering and supporting racism applies to education (sic) about our Native Americans, Black Americans, Asian peoples, even Irish and Italian. Our Black citizens are hard at work using their resources and political savvy to overturn centuries of misrepresentation. Muslims can do it too. We must. Muslim comedians have broken the ground; the next step is to make our own films.

Analysis has its limits; film is a powerful artistic tool that can sweep aside all arguments and misunderstandings.

Barbara Nimri Aziz is a New York based anthropologist and journalist. Find her work at www.RadioTahrir.org. She was a longtime producer at Pacifica-WBAI Radio in NY.

This article was first published by CounterPunch