History of World War II: Operation Barbarossa, the Allied Firebombing of German Cities and Japan’s Early Conquests

Global Research E-Book, Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG)

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

First published by Global Research on May 8, 2022

History of World War II

Operation Barbarossa

The Allied Firebombing of German Cities and Japan’s Early Conquests

by Shane Quinn

First published on April 2, 2022

About the Author

Shane Quinn was born in Dublin, Ireland and lives just outside the Irish capital city. He studied journalism at Griffith College Dublin for four years and acquired a BA honors journalism degree in 2010. He works in the editing business and is a prolific writer of articles online, focusing on subjects from NATO expansionism to the world wars. He has a firm interest in the environment and, in an amateur capacity, studies ornithology mainly in monitoring local bird populations.

He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

Table of Contents

Preface

Part I

The Nazi-Soviet War

Chapter I

Operation Barbarossa. Did Stalin Foresee Hitler’s Invasion?

Chapter II

Hitler’s Secret Directive 18

Chapter III

Nazi Germany’s Economic Exploitation of the USSR

Chapter IV

Why Nazi Germany Failed to Defeat the Soviet Union

Chapter V

Operation Barbarossa, an Overview

Chapter VI

Hitler’s Early Victories, the Wolf’s Lair Headquarters

Chapter VII

Operation Barbarossa, Analysis of Early Fighting

Chapter VIII

Germans Surround Kiev and Leningrad

Chapter IX

Germany’s Advance into Eastern Ukraine and Crimea

Chapter X

The Brutal Conduct of Operation Barbarossa

Chapter XI

The Battle of Moscow

Chapter XII

The Battle of Moscow, Soviet Counterattack

Chapter XIII

Consequences of the November 1941 Orsha Conference

Chapter XIV

Analysis of Germany’s 1942 Offensive

Chapter XV

The Allied Firebombing of German Cities

Chapter XVI

Western Allies Terror-bombed 70 German Cities

Chapter XVII

Fallacy of Terror-bombing Urban Areas

Chapter XVIII

Red Army Winter Counteroffensive

Chapter XIX

The Red Army’s Winter Campaign, Part II

Chapter XX

Nazi-Soviet War Destined to Become a Long War

Chapter XXI

Overview of the Nazi-Soviet War in Early 1942

Part II

The Asia-Pacific War

Chapter XXII

Pearl Harbor and the Early Japanese Advances

Chapter XXIII

The Japanese Assault on Northern Malaya

Chapter XXIV

The Japanese March Through Southern Malaya and Singapore’s Outskirts

Chapter XXV

The Japanese Capture of Singapore. The “Largest Capitulation in British History”

Chapter XXVI

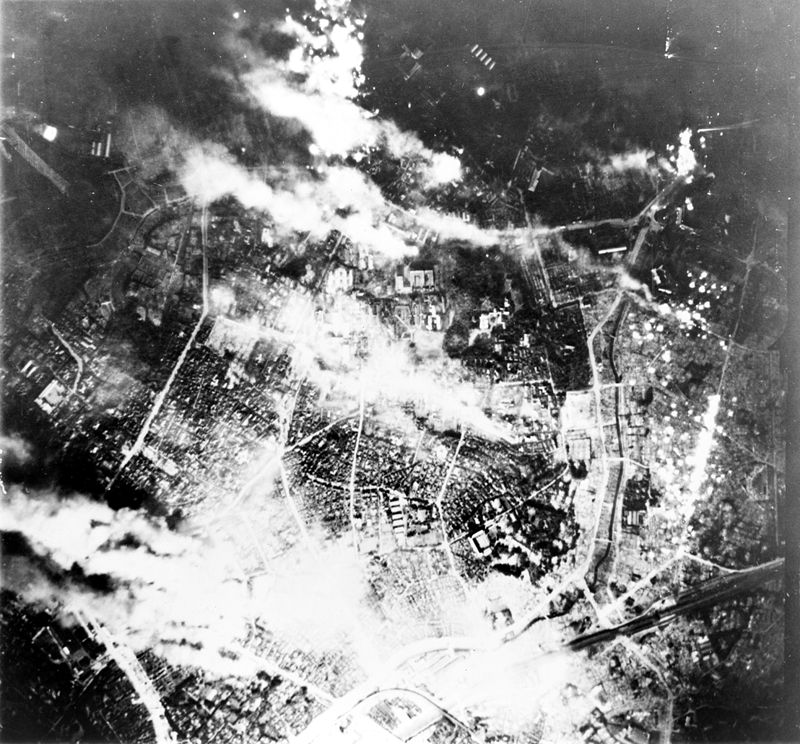

The US Firestorming of Tokyo Rivaled the Hiroshima Bombing

Preface

This book is entitled History of World War II: Operation Barbarossa, the Allied Firebombing of German Cities and Japan’s Early Conquests.

The first two chapters focus on German preparations as they geared up to launch their 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union, called Operation Barbarossa, which began eight decades ago. It was named after King Frederick Barbarossa, a Prussian emperor who in the 12th century had waged war against the Slavic peoples. Analysed also in the opening two chapters are the Soviet Union’s preparations for a conflict with Nazi Germany.

The remaining chapters focus for the large part on the fighting itself, as the Nazis and their Axis allies, the Romanians and Finns at first, swarmed across Soviet frontiers in the early hours of 22 June 1941. The German-led invasion of the USSR was the largest military offensive in history, consisting of almost four million invading troops. Its outcome would decide whether the post-World War II landscape comprised of an American-German dominated globe, or an American-Soviet dominated globe. The Nazi-Soviet war was, as a consequence, a crucial event in modern history and its result was felt for decades afterward and, indeed, to the present day.

Within the first four weeks of Operation Barbarossa, by mid-July 1941 the Germans had advanced more than two-thirds of the way to Moscow. Few outsiders would have given the Russians much of a chance at this point. However, the Soviet leadership did not panic, nor did the Red Army collapse as the French had done the year before.

The Nazi invasion was the most brutal the world had ever seen. In 1941 alone millions of Soviet citizens, both military personnel and non-combatants, would either be killed or sent to concentration camps. The murderous nature of the Nazi occupation led to increased resistance from the Soviet Army and local populations, many of whom came to despise the occupiers and joined partisan groups.

Covered here are some key aspects of Barbarossa from the German and Soviet viewpoints, such as intelligence reports warning of the coming German invasion, what impact the purges of the Soviet military command had on the Red Army, strategic errors committed by the Nazi hierarchy, German arrogance and underestimation of Russian fighting capacity and resources, vastness of the Soviet terrain and logistical problems. The German soldiers were led to believe that the Soviet Union was a primitive, technologically backward state, and the surprise was all the greater when they came across military hardware superior to their own, like the Soviet T-34 and KV tanks.

The turning point of World War II is often regarded to be the Battle of Stalingrad, which began in August 1942; but the author argues that the really critical fighting and developments occurred a year before this, in the course of Barbarossa, which officially ended in German failure with the Red Army counterattack on 5 December 1941. The Soviets’ ability to absorb and eventually overcome the Wehrmacht’s blows saved humanity from the nightmare of a Nazi victory, in which case Adolf Hitler would have held dominance over much of Eurasia and perhaps further afield.

Part I

The Nazi-Soviet War

Chapter I

Operation Barbarossa. Did Stalin Foresee Hitler’s Invasion?

In attacking eastwards from June 1941 the Nazis intended to annex the Ukraine, all of European Russia, the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, while establishing a satellite Finnish nation to the north-east. A greatly enlarged Germany would thus be created, serving as a homeland for hundreds of millions of those belonging to the so-called Germanic and Nordic races. As envisaged by Nazi planners, this expansion would provide the economic base to sustain the thousand year Reich.

According to Adolf Hitler’s Directive No. 18 issued on 12 November 1940, the goal of his eastern invasion was to occupy and hold a line from Archangel, in the far north-west of Russia, to Astrakhan, almost 1,300 miles southward; further conquering Leningrad, Moscow, the Donbas, Kuban (in southern Russia) and the Caucasus.

Nothing was mentioned as to what the Germans would do, once the Archangel-Astrakhan line had been reached. The Wehrmacht’s objective was, however, to annihilate the Soviet forces in western Russia through massive armoured spearheads and encirclements, thereby preventing the Red Army’s withdrawal further east.

It should be stated, firstly, that the USSR had no plans in 1940 or 1941 to attack Nazi Germany; nor did the Soviets hold ambitions to sweep across all of mainland Europe in a war of conquest. There really was no need for the world’s largest state to take control of other vast continents.

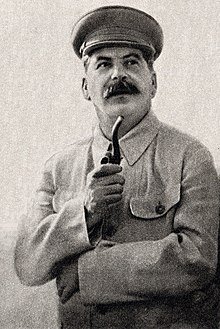

David Glantz, the US military historian and retired colonel, realised that Soviet ruler Joseph Stalin’s position in 1941 was that of a defensive one. Glantz wrote how, “Stalin was guilty of wishful thinking, of hoping to delay war for at least another year, in order to complete the reorganization of his armed forces. He worked at a fever pitch throughout the spring of 1941, trying desperately to improve the Soviet Union’s defensive posture while seeking to delay the inevitable confrontation”. (1)

Glantz’ views are supported by other experienced historians like England’s Antony Beevor. He observed that “the Red Army was simply not in a state to launch a major offensive in the summer of 1941”; but Beevor did not entirely exclude the possibility that Stalin “may have been considering a preventive attack in the winter of 1941, or more probably in 1942, when the Red Army would be better trained and equipped”. (2)

Was the Soviet leadership aware of the threat that Hitler posed to their state?; and which was gradually developing around them like a dark cloud. Early in July 1940 a report compiled by the Soviet intelligence agency, the NKGB, was sent to the Kremlin. It revealed that the Third Reich’s General Staff had requested Germany’s Transport Ministry to furnish details, regarding rail capacities for Wehrmacht soldiers to be shifted from west to east (3). It constituted the first hint of what lay ahead. This was the period, in the high summer of 1940, when serious discussions started between Hitler and his generals, relating to an attack on Russia.

As early as 31 July 1940 the German planning for an invasion of the Soviet Union “was in full swing”, as noted by US author Harrison E. Salisbury (4). Earlier in July Hitler had initially pondered attacking Russia in the autumn of 1940 but, by late July, he concluded it was too late in the year with poor weather fast approaching.

There is little indication that Stalin, or high-ranking Soviet officials, were at all worried by the first warning signals they received through intelligence about Nazi intentions. During early August 1940, the British obtained information suggesting Hitler was planning to destroy Russia, and London passed on their findings to Moscow (5). Stalin ignored them as he strongly distrusted the British, not without some reason. This was based in part on Stalin’s recent experiences in dealing with Conservative governments who were, to put it kindly, of an unfriendly disposition towards the Soviet Union.

London and Paris refused to sign a pact with the Kremlin in the spring and summer of 1939 – which would have aligned the British, French and Russians against Nazi Germany (6). Stalin had no choice but to then finalise an agreement with Hitler that autumn, and these unwanted realities have since been suppressed by institutions like the German-led European Union.

The Nazi-Soviet Pact of 23 August 1939 had served the Soviets well, until the Wehrmacht swiftly routed France from May to June 1940. The manner of the French defeat astonished and disturbed Stalin, who was expecting a long, drawn-out conflict in the west, as in the First World War.

Yet Stalin’s agreement with Hitler had kept Russia out of the heavy fighting for now, while the Kremlin made territorial gains by taking over the eastern half of Poland, on 6 October 1939. With the end of the Winter War against Finland, the Soviets absorbed around 10% of Finnish land in March 1940. At the beginning of August 1940 Stalin officially annexed the Baltic nations of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, having first occupied those states in mid-June 1940, which resulted in pro-German officials fleeing the region (7). Stalin’s march into the Baltic came as a response to the Nazi triumphs on the western front, and his understandable fear of Baltic nationalism and possible German penetration near Soviet frontiers.

Basil Liddell Hart, the retired British Army captain and military theorist wrote, “Hitler had agreed that the Baltic states should be within the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence, not to their actual occupation; and he felt that he had been tricked by his partner; although most of his advisers realistically considered the Russian move into the Baltic states to be a natural precaution, inspired by fear of what Hitler might attempt after his victory in the west”. (8)

During the days after the Fall of France, Stalin occupied the Romanian territories of Northern Bukovina and Bessarabia. Until World War I, Bessarabia had belonged to the Russian Empire for about a century, but Northern Bukovina never before comprised part of Russia. In the eyes of Hitler and German generals, Stalin’s advance into parts of northern Romania was dangerous and provocative. Hitler first learnt of Stalin’s plan to reincorporate Bessarabia on 23 June 1940, when just after sunrise the Nazi leader was victoriously touring Paris in an open topped vehicle (9). Hitler became irritated when he heard the news. He felt that Bessarabia’s return to Russia would bring Stalin intolerably close to the Axis oil wells, at the city of Ploesti in southern Romania.

During a meeting with Benito Mussolini in the Bavarian Alps on 19 January 1941, Hitler told his Italian counterpart, “now in the age of airpower, the Romanian oil fields can be turned into an expanse of smoking debris by air attack from Russia and the Mediterranean, and the life of the Axis depends on these oil fields”. (10)

Over the course of World War II, Ploesti’s wells furnished the Nazi empire with at least 35% of its entire oil, other accounts state as much as 60%; but the latter figure is most likely excessive and above the overall average (11) (12). For many years Romania was Europe’s largest oil producing country by far, and the fifth biggest on earth in 1941 and 1942, having overtaken Mexico. The significant oil sources in Indonesia (Dutch East Indies) fell under Axis control in early 1942, when that country was overrun by Japanese armies, and they would remain there for over three years.

Hitler wanted his Romanian oil fields to be formidably defended; he ordered the Wehrmacht to place scores of heavy and medium German anti-aircraft guns around the Ploesti refineries, and that smoke screens also be deployed; the latter were effective at obscuring the installations from enemy planes, which were shot down in large numbers.

The Germans created limited quantities of oil from synthetic hydrogenation processes, involving materials like coal. This mostly benefited the Luftwaffe, not so much the panzers and other ground vehicles. The terms of the non-aggression deal with Russia ensured the Reich received in total 900,000 tons of Soviet oil, from September 1939 to June 1941. This was not a huge amount, considering the Wehrmacht consumed three million tons of oil in 1940 alone. (13)

Nazi Germany was also supplied with oil by the United States, then unrivalled as the world’s biggest oil producer and exporter; specifically the dealings that American corporations like Texaco and Standard Oil conducted with the Nazis, sometimes secretly through other countries, along with US-controlled subsidiaries based in the Reich (14). In addition, arriving from the globe’s third largest oil manufacturing state, Venezuela, then a major US client, came shipments of petroleum sent across the Atlantic, destined for the German war machine.

Altogether “around 150 American companies” had “business links to Nazi Germany”, the Israeli journalist Ofer Aderet outlined, writing for the left-leaning newspaper Haaretz. US business deals with the Nazis, Aderet wrote, “included huge loans, large investments, cartel agreements, the construction of plants in Germany as part of the Third Reich’s rearmament, and the supply of massive amounts of war matériel. (15)

Meanwhile, Stalin’s reintegration of Bessarabia in early July 1940 was providing a buffer to the Soviet defence of its navy, in the Black Sea slightly further east; including added security to Russian naval bases, such at the port of Odessa in southern Ukraine. The Soviet advance into Romania “was worse than ‘a slap in the face’ for Hitler”, Liddell Hart observed as “it placed the Russians ominously close to the Romanian oil fields on which he counted for his own supply”. On 29 July 1940 Hitler spoke to his Chief-of-Operations, General Alfred Jodl, about the potential of fighting Russia if Stalin attempted to seize Ploesti. (16)

On 9 August 1940 General Jodl issued a directive titled “Reconstruction East”, ordering that German transport and supplies be bolstered in the east, so that plans would be cemented by the spring of 1941 for an attack on Russia (17). It was at this time that Winston Churchill’s government began warning Moscow of the German invasion plans; but Stalin strongly suspected that the British wanted to drag him into the war, just to take the pressure off London. Stalin certainly believed that Soviet armies would have to fight the Germans some day, but not just yet.

Soviet designs towards Germany remained non-threatening. On 1 August 1940 the Soviet Union’s foreign minister, Vyacheslav Molotov, said that the Nazi-Soviet Pact was centred not on “fortuitous considerations of a transient nature, but on the fundamental political interests of both countries” (18). Nevertheless by September 1940, Soviet commanders stationed along their western frontier began talking about Hitler’s “Drang nach Osten”, meaning the dictator’s proposal for eastward expansion. Soviet military men spoke about Hitler’s habit of carrying around a picture of Frederick Barbarossa, the red-bearded Prussian emperor who centuries before had waged war against the Slavs. (19)

On 12 November 1940 foreign minister Molotov, a staunch communist, landed in Germany by aircraft. Upon Molotov’s arrival in Berlin, Stalin told him to indicate to the Germans that he wanted a wide-ranging deal with them. Stalin still thought a partnership with Hitler into the near future was attainable. Instead, during the talks Nazi officials presented to Molotov a junior partnership for Soviet Russia, in a German-dominated global alliance. Soviet policy, as the Nazis insisted, was to be focused on south Asia, towards India, and a conflict with Britain. This did not satisfy Stalin at all.

Following Molotov’s dispatching of the report on his disappointing discussions in Berlin, according to Yakov Chadaev, a Soviet administrator, Stalin was certain that Hitler intended to wage war on Russia. Less than two weeks later, on 25 November 1940 Stalin informed the Bulgarian communist politician Georgi Dimitrov “our relations with Germany are polite on the surface, but there is serious friction between us”. (20)

Marshal Aleksandr Vasilevsky, a top level Russian officer who repeatedly met with Stalin, had accompanied Molotov to Berlin. Vasilevsky returned home convinced that Hitler would invade the Soviet Union (21). Vasilevsky’s opinion was shared by many of his Red Army colleagues. After Molotov had left Berlin, Hitler met German executives and made it clear to them that he was going to attack Russia.

In the autumn of 1940 draft plans for the strategic positioning of Soviet divisions along their western frontier, in preparation for a German invasion, were sent to the Kremlin by the Russian High Command. Stalin did not respond. Rather ominously, in the second half of November 1940 the central European countries of Hungary, Slovakia and Romania all joined Hitler’s new European order, by signing up to the Axis coalition. Hitler could now depend especially on the support of Romania, under Ion Antonescu. He was a fervently anti-communist and anti-Semitic military dictator, who at age 58 had come to power on 4 September 1940.

Romania is by no means a leading nation today, but during the war years it was indeed an important country. This was mostly due to her natural resources and to a lesser extent its strategic location, beside the Black Sea and the Ukraine.

Stalin was growing slightly concerned as 1940 reached its end. Addressing Soviet generals before Christmas, Stalin referenced passages from Hitler’s book ‘Mein Kampf’, and he spoke of the Nazi leader’s stated goal of attacking the USSR some day. Stalin said “we will try to delay the war for two years”, until December 1942 or into 1943. Shortly after the Wehrmacht’s crushing of the French, Molotov recalled him saying, “we would be able to confront the Germans on an equal basis only by 1943”. (22)

On 18 December 1940 Hitler released his Directive No. 21 outlining, “The German armed forces must be prepared to crush Soviet Russia in a quick campaign, before the end of the war against England”. On Christmas Day 1940, the Soviet military attaché in Berlin received an anonymous letter. It expounded that the Germans were preparing a military operation against Russia, for the spring of 1941. (23)

By 29 December 1940 Soviet intelligence agencies had possession of the basic facts regarding Operation Barbarossa, its design and planned start date (24). In late January 1941 the Japanese military diplomat Yamaguchi, returning to the Russian capital from Berlin, said to a member of the Soviet naval diplomatic service, “I do not exclude the possibility of conflict between Berlin and Moscow”.

Yamaguchi’s remark was forwarded on 30 January 1941 to Marshal Kliment Voroshilov, a prominent Soviet officer who knew Stalin personally. Even before late January 1941, the Soviet Defence Commissariat was concerned enough to draft a general directive to the Russian border commands and fleets, which for the first time would name Germany as the probable enemy in coming war.

In early February 1941, the Soviet Naval Commissariat started receiving almost daily accounts, about the arrival of German Army specialists in Bulgarian ports; and preparations for the installment of German coastal armaments there. This information was relayed to Stalin on 7 February 1941. In fact, other senior figures such as Marshal Filipp Golikov, the chief of intelligence for the USSR’s General Staff, said that all Soviet reports on German planning were forwarded to Stalin himself. (25)

As Molotov was about to make his way to Berlin the previous November, Stalin stressed to him that Bulgaria is “the most important question of the negotiations” and should be placed in the Soviet realm (26). On 1 March 1941 Bulgaria instead joined the Axis. In early February 1941, the Russian command in Leningrad reported German troop movements in Finland. This was no laughing matter as Finland shares an eastern border with Russia.

The Kremlin could not count on Finnish loyalty in the event of a German attack. Finland’s Commander-in-Chief Gustaf Mannerheim, in his mid-70s and an anti-Bolshevik, had been closely acquainted with the deposed Russian Tsar Nicholas II. Mannerheim previously kept a portrait of the Tsar and said, “He was my emperor”. The Finns were far from grateful when the Soviet military rolled into their country in November 1939, without a declaration of war. In February 1941 the Leningrad Command reported German conversations with Sweden, pertaining to the transit of Wehrmacht troops through Swedish land.

The Soviet political administration wanted to emphasize awareness to the Red Army, to be prepared for engagement. Stalin rejected this approach, because he was afraid it would appear to Hitler that he was gathering forces to start an offensive against Germany. Stalin warned General Georgy Zhukov that “Mobilisation means war”, and he did not want to risk a conflict with Germany in 1941. (27)

On 15 February 1941, a German typist entered the Soviet consulate in Berlin. He brought with him a German-Russian phrase book, which was being published in his printing shop in extra large edition – included in it were such phrases as, “Are you a Communist?”, “Hands up or I’ll shoot” and “Surrender” (28). The ramifications were clear enough. Around this time, Russian State Security acquired reliable intelligence stating that the German invasion of Britain was suspended indefinitely, until Russia was defeated.

In late February and early March 1941, German reconnaissance flights were taking place over the Baltic states under Russian control. These were severe infringements into the Soviet zone. The appearance of Nazi planes became frequent over the coastal city of Libau, in western Latvia, above the Estonian capital Tallinn, and over Estonia’s largest island Saaremaa.

Russian Admiral Nikolai Kuznetsov, who intensely disliked the fascist states, granted the Soviet Baltic fleet authority to open fire on German aircraft. On 17 and 18 March 1941, Luftwaffe planes were spotted over Libau and promptly shot at by Soviet personnel (29). Nazi aircraft were then sighted near the city of Odessa, on the Black Sea. Admiral Kuznetsov was summoned to the Kremlin by Stalin, where he found him with the police chief Lavrentiy Beria. Stalin reprimanded Kuznetsov for giving the order to shoot at German planes, and he expressly forbid Soviet units to do so again.

Notes

1 David M. Glantz, Operation Barbarossa: Hitler’s Invasion of Russia, 1941 (The History Press; Illustrated Edition, 1 May 2011) p. 20

2 Antony Beevor, The Second World War (Weidenfeld & Nicolson Ltd., UK edition, 18 Sep. 2014) Chapter 12, Barbarossa

3 Harrison E. Salisbury, The 900 Days: The Siege of Leningrad (Da Capo Press, 30 Sep. 1985) p. 57

4 Ibid.

5 John H. Waller, The Unseen War in Europe: Espionage and Conspiracy in the Second World War (Random House USA Inc.; 1st edition, 9 Apr. 1996) p. 192

6 Donald J. Goodspeed, The German Wars (Random House Value Publishing, 2nd edition, 3 Apr. 1985) p. 323

7 Anna Louise Strong, The Stalin Era (Mainstream Publishers, 1 Jan. 1956) p. 89

8 Basil Liddell Hart, A History of the Second World War (Pan, London, 1970) p. 143

9 Roger Moorhouse, The Devils’ Alliance (Basic Books, 13 Oct. 2014) p. 107

10 Liddell Hart, A History of the Second World War, p. 147

11 Scott E. Wuesthoff, The Utility of Targeting the Petroleum-based Sector of a Nation’s Economic Infrastructure, Chapter 2, Unlimited War and Oil, Air University Press, 1 June 1994, p. 5 of 8, Jstor

12 Jason Dawsey, “Over the Cauldron of Ploesti: The American Air War in Romania”, The National World War II Museum, 12 August 2019

13 Clifford E. Singer, Energy And International War (World Scientific Publishing; Illustrated edition, 3 Dec. 2008) p. 145

14 Jacques R. Pauwels, “Profits über Alles! American corporations and Hitler”, Global Research, 7 June 2019

15 Ofer Aderet, “U.S. Chemical Corporation DuPont Helped Nazi Germany Because of Ideology, Israeli Researcher Says”, Haaretz, 2 May 2019

16 Liddell Hart, A History of the Second World War, p. 143

17 Gerhard L. Weinberg, Germany and the Soviet Union, 1939-1941 (E. J. Brill, 1 Jan. 1972) p. 112

18 Geoffrey Roberts, Stalin’s Wars (Yale University Press, 1st edition, 14 Nov. 2006) p. 57

19 Salisbury, The 900 Days, p. 57

20 Roberts, Stalin’s Wars, p. 61

21 Salisbury, The 900 Days, p. 57

22 Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography (Pan; Reprints edition, 16 Apr. 2010) p. 406

23 Salisbury, The 900 Days, p. 58

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid., p. 61

26 Roberts, Stalin’s Wars, p. 58

27 Geoffrey Roberts, “Last men standing”, The Irish Examiner, 22 June 2011

28 Salisbury, The 900 Days, pp. 58-59

29 Ibid., p. 59

Chapter II

Hitler’s Secret Directive 18

After the failed November 1940 discussions in Berlin, of the Soviet Union’s foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov, both he and his leader Joseph Stalin occasionally remarked that Nazi Germany was no longer so prompt in fulfilling its obligations to Moscow. This was relating to the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact, of 23 August 1939, an agreement which was meant to last for 10 years. Stalin and Molotov did not attribute much significance to the slacking off in Berlin’s punctuality, as the delivery of German goods and technology to Soviet Russia increasingly did not appear on schedule.

Unknown to Stalin and Molotov, on the very day the Soviet foreign minister had landed in Berlin for talks, 12 November 1940, Adolf Hitler secretly issued Directive No. 18. It outlined the planned German invasion of the USSR, including the envisaged conquest of major cities like Kiev, Kharkov, Leningrad and Moscow. On 18 December 1940 Führer Directive No. 21 was completed, which stated that the Wehrmacht’s attack on the Soviet Union should proceed in mid-May 1941.

For Russia, as 1941 advanced beyond its opening weeks, the warning signs about the German threat were becoming difficult to overlook. False reports were featured in the Nazi press about “military preparations” being made across the border in the Soviet camp. The same German media tactics had preceded Hitler’s invasions of Czechoslovakia and Poland.

On 23 February 1941, the Soviet Defence Commissariat published a decree stating that Nazi Germany was the next likely enemy (1). Soviet frontier areas were requested to make the necessary preparations to repel the attack, but the Kremlin did not respond.

On 22 March 1941, the Russian intelligence agency NKGB obtained what it believed to be solid material that “Hitler has given secret instructions to suspend the fulfillment of orders for the Soviet Union”, regarding shipments tied to the Nazi-Soviet Pact. For example the Czech Skoda plant, under Nazi control, had been ordered to halt deliveries to Russia. On 25 March 1941 the NKGB produced a special report, expounding that the Germans had amassed 120 divisions beside the Soviet border. (2)

For months there were concerning cables coming from the Russian military attaché in Nazi-occupied France, General Ivan Susloparov. The German authorities had curtailed Soviet embassy duties in France, and in February 1941 the Russian embassy was moved from Paris southwards to Vichy, in central France. Only a Soviet consulate was left in Paris.

Image on the right: OKH commander Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch and Hitler study maps during the early days of Hitler’s Russian Campaign (Public Domain)

During April 1941, General Susloparov informed Moscow that the Germans would attack Russia in late May 1941. Slightly later on, he explained it had been delayed for a month due to bad weather. At the end of April, General Susloparov collected further information about the German invasion through colleagues from Yugoslavia, America, China, Turkey and Bulgaria (3). This intelligence was forwarded to Moscow by mid-May 1941.

Again in April 1941, a Czech agent reported that the Wehrmacht was going to execute military operations against the Soviet Union. The report was sent to Stalin, who became angry when he read it and replied, “This informant is an English provocateur. Find out who is making this provocation and punish him”. (4)

On 10 April 1941 Stalin and Molotov were given a summary by the NKGB, about a meeting that Hitler had with Prince Paul of Yugoslavia at the Berghof, in early March 1941 (5). Hitler was described as telling Prince Paul he would begin his invasion of Russia in late June 1941. Stalin’s response to the alarming reports, such as this, was one of appeasement of Hitler, though a similar strategy had failed for the Western powers.

Remarkably, through April 1941 Stalin increased the volume of shipments of Russian supplies to the Third Reich, amounting to: 208,000 tons of grain, 90,000 tons of oil, 6,340 tons of metal, etc (6). Much of these essentials would be used by the Nazis in their attack on Russia.

Marshal Filipp Golikov, head of intelligence for the USSR’s General Staff, insisted that all Soviet reports relating to Nazi plans were forwarded directly to Stalin. Other accounts informing Moscow about an impending Wehrmacht invasion came from abroad too. As early as January 1941 Sumner Welles, an influential US government official, warned the Soviet Ambassador to America, Konstantin Umansky, that Washington had information showing Germany would engage in war against Russia, by the spring of 1941. (7)

During the final week of March 1941 US Army cryptanalysts, experts at deciphering codes, started producing obvious indications of a German relocation to the east. This material was relayed to the Soviets (8). America’s cryptographers had cracked Japanese codes in the second half of 1940; including the Purple Cipher, Japan’s highest diplomatic code, which ensured that the Franklin Roosevelt government was uniquely well informed of Tokyo’s intentions.

The US commercial attaché in Berlin, Sam E. Woods, came into contact with high-level German staff officers opposed to the Nazi regime. They were aware of the planning for Operation Barbarossa. Woods was in a position to discreetly observe the German preparations from July 1940, until December of that year. Woods sent his findings to Washington. President Roosevelt agreed that the Kremlin should be told of these developments. On 20 March 1941, Welles once more saw Soviet Ambassador Umansky and forwarded the news. (9)

Russia’s embassy in Berlin noticed that the Nazi press was reprinting passages from Hitler’s 1925 book ‘Mein Kampf’. The paragraphs in question were about his proposal for “lebensraum”, German enlargement at the Soviet Union’s expense.

Image below: German troops at the Soviet state border marker, 22 June 1941 (Public Domain)

The Russians had a formidable espionage agent, Richard Sorge, operating in Tokyo since 1933, the year that Hitler took power in Germany. Sorge, a German citizen and committed communist, established an especially close relationship with the imprudent Nazi ambassador to Japan, General Eugen Ott. The data Sorge received was not always 100% accurate, but it allowed him access to the most confidential and up to date German plans.

On 5 March 1941, Sorge dispatched to the Soviets a microfilm of a German telegram sent by the foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, to the German ambassador Ott – and which outlined that the Wehrmacht attack on Russia would fall in mid-June 1941. On 15 May, Sorge reported to Moscow that the German invasion would start somewhere between 20 to 22 of June (10). A few days later on 19 May Sorge cabled, “Against the Soviet Union will be concentrated nine armies, 150 divisions”. He later increased this figure to between 170 to 190 divisions, and that Operation Barbarossa will start without an ultimatum or declaration of war.

All of this fell on deaf ears. Sorge, who had his vices being a heavy drinker and womaniser, was ridiculed by Stalin just before the Germans attacked as someone “who has set up factories and brothels in Japan”. To be fair to Stalin, at the late date of 17 June 1941 Sorge was not fully certain if Barbarossa would go ahead (11). Why? The German military attaché in Tokyo became unsure if it would proceed, and sometimes a spy is only as good as his or her sources.

Meanwhile in March 1941, Russia’s State Security forces acquired an account about a meeting the Romanian autocrat, Ion Antonescu, had with a German official named Bering, where the subject of war with Russia was discussed. Antonescu had in fact been informed by Hitler, as early as 14 January 1941, of the German plan to invade Russia, such was the prominent position Romania held in Nazi war aims. The German-controlled Ploesti refineries in southern Romania produced 5.5 million tons of oil in 1941, and 5.7 million tons in 1942. (12)

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini learnt of the German attack on Russia only after it had commenced – in part because Hitler believed he did not really need Italy, he had not asked for their help; and it was also hardly Italy’s fight, considering that country’s position cut adrift somewhat in south-central Europe. The Italian people, furthermore, would not want their troops involved in a brutal conflict against Russia, and which had nothing to do with Italy. The Duce had other ideas, and after the war the Austrian commando Otto Skorzeny correctly wrote, “Benito Mussolini was not a good wartime leader”. (13)

By mid-March 1941, the Soviet leadership had a detailed description of the Barbarossa plan (14). The period, throughout March and early April 1941, saw tensions rise significantly between Berlin and Moscow, notably in south-eastern Europe. The American author Harrison E. Salisbury noted, “This was the moment in which Yugoslavia with tacit encouragement from Moscow defied the Germans, and in which the Germans moved rapidly and decisively to end the war in Greece, and occupy the whole of the Balkans. When Moscow signed a treaty with Yugoslavia on April 6 – the day Hitler attacked Belgrade – the German reaction was so savage that Stalin became alarmed”. (15)

On 25 March 1941 the Yugoslav government of the regent, Prince Paul, had signed an agreement in Vienna, which effectively made Yugoslavia a Nazi client state. Nevertheless, just two days later patriotic factions in the Serbian populace, assisted by British agents and led by chief of the Yugoslav air force, General Dusan Simovic, overthrew the pro-German regency. They installed a monarchy headed by the teenage king, Peter II of Yugoslavia; and a new government was formed in the capital Belgrade which declared its neutrality. Upon hearing this, Winston Churchill declared it to be “great news” and that Yugoslavia had “found its soul” while it would receive from London “all possible aid and succour”. (16)

Hitler was irate at Churchill’s gloating and the sudden reversal in Yugoslav policy. Feeling he had been betrayed somehow, he decided to teach the Yugoslavs a lesson. Hitler ordered his Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring to launch a furious air attack on Belgrade. In the days from 6 April 1941, thousands of people were killed in Belgrade from Nazi air raids. On the ground Yugoslav forces were no match for the Germans, who were helped by the Italians, and the fighting was all over after less than two weeks. Churchill’s aid and succour was sadly not forthcoming.

The Nazi-led Axis powers likewise invaded Greece on 6 April 1941, and by the middle of that month the Greek position had become untenable (17); therefore on 24 April British forces in Greece began their evacuation of the country. This was an operation the British had by now developed a real expertise in, as to escape the German blows they previously evacuated Dunkirk, Le Havre and Narvik.

Because of his subjugation of Yugoslavia and Greece, Hitler on 30 April 1941 postponed the attack on the Soviet Union until 22 June. It has sometimes been claimed that this delay, of just over five weeks, was a central factor in later derailing Barbarossa. Though an attractive one, this theory does not stand up under closer inspection.

The Nazi invasion eventually petered out, but largely due to strategic errors committed by the German high command and Hitler, such as not directing the majority of their forces towards Moscow, the USSR’s communications centre. Moreover, Canadian historian Donald J. Goodspeed observed, “the middle of May was really too early for an invasion of Russia. Before the middle of June, late spring rains would ruin the roads, flood the rivers, and make movement very difficult except on the few paved highways. Thus, since the initial surprise thrust had to go rapidly to yield the best results, Hitler probably gained more than he lost by his postponement”. (18)

The spring and early summer of 1941 were particularly wet, across eastern Poland and the western parts of European Russia. Had the Germans invaded as originally intended on 15 May 1941, their advance would have bogged down in the first weeks. It is interesting to note that the Polish-Russian river valleys were still overflowing on 1 June, according to the American historian Samuel W. Mitcham. (19)

On 3 April 1941 Churchill attempted to warn Stalin, through the British ambassador to Russia, Stafford Cripps, that London’s intelligence data indicated the Germans were preparing an attack on Russia. Stalin gave no credence whatever to British intelligence reports, because he was distrustful of Britain even more so than America, and it is likely such warnings if anything increased his suspicions further.

In late April 1941 Jefferson Patterson, the First Secretary of the US Embassy in Berlin, invited his Russian counterpart Valentin Berezhkov to cocktails at his home. Among the invitees was a Luftwaffe major, apparently on leave from North Africa. Late in the evening this German major confided to Berezhkov, “The fact is I’m not here on leave. My squadron was recalled from North Africa, and yesterday we got orders to transfer to the east, to the region of Lodz [central Poland]. There may be nothing special in that, but I know many other units have also been transferred to your frontiers recently” (20). Berezhkov was disturbed to hear this, and never before had a Wehrmacht officer divulged top secret news like that. Berezhkov passed on what he heard to Moscow.

Throughout April 1941, daily bulletins from the Soviet General Staff and Naval Staff outlined German troop gatherings along the Russian frontier. On 1 May an account from the General Staff to the Soviet border military districts stated, “In the course of all March and April… the German command has carried out an accelerated transfer of troops to the borders of the Soviet Union”. Try as the Germans might, it was impossible for them to conceal the gathering of vast numbers of their soldiers. The German presence was obvious along the central River Bug boundary; the Soviet chief of frontier guards asked Moscow for approval to relocate the families of Red Army troops further east. Permission was not granted and the commander was upbraided for showing “panic”. (21)

Nazi reconnaissance flights, near or over Soviet territory, were increasing as the spring of 1941 continued. Between 28 March and 18 April, the Russians said that German planes had been sighted 80 times making incursions. On 15 April, a German aircraft was forced into an emergency landing near the city of Rovno, in western Ukraine. On board a camera was found, along with exposed film and a map of the USSR (22). The German chargé d’affaires in Moscow, Werner von Tippelskirch, was summoned to the Foreign Commissariat on 22 April 1941. He met stiff protestations about the German overflights.

Yet Nazi planes were hardly ever shot at, because Stalin forbade the Soviet armed forces from doing so, for fear of provoking an invasion. In early May 1941 the German propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary, “Stalin and his people remain completely inactive. Like a rabbit confronted by a snake”. (23)

On 5 May 1941 Stalin received from his intelligence agencies a report detailing, “German officers and soldiers speak openly of the coming war, between Germany and the Soviet Union, as a matter already decided. The war is expected to start after the completion of spring planting”. Also on 5 May Stalin gave a speech to young Soviet officers at the Kremlin, and he spoke seriously of the Nazi threat. “War with Germany is inevitable” Stalin said, but there is no sign the Soviet ruler believed a German attack was imminent. (24)

On 24 May 1941, the head of the German western press department, Karl Bemer, got drunk at a reception in the Bulgarian embassy in Berlin. Bemer was heard roaring “we will be boss of all Russia and Stalin will be dead. We will demolish the Russians quicker than we did the French” (25). This incident quickly came to the attention of Ivan Filippov, a Russian correspondent in Berlin working for the TASS news agency. Filippov, also a Soviet intelligence operative, heard that Bemer was thereafter arrested by German police.

In early June 1941 Admiral Mikhail Vorontsov, the Russian naval attaché in Berlin, telegrammed his fellow Admiral Nikolai Kuznetsov, who was in Moscow, and stated that the Germans would invade around the 20th to the 22nd of June. Kuznetsov checked to see if Stalin was given a copy of this telegram, and he found that he certainly received it. (26)

Notes

1 Harrison E. Salisbury, The 900 Days: The Siege of Leningrad (Da Capo Press, 30 Sep. 1985) p. 59

2 Ibid., p. 60

3 Ibid., p. 61

4 Robert H. McNeal, Stalin: Man and Ruler (Palgrave Macmillan, 1st edition, 1988) p. 237

5 Salisbury, The 900 Days, p. 63

6 United States Congress, Proceedings and Debates of the U.S. Congress, Volume 94, Part 9, p. 366

7 Salisbury, The 900 Days, pp. 61-62

8 John Simkin, “Operation Barbarossa”, Spartacus Educational, September 1997 (Updated January 2020)

9 Ibid.

10 Salisbury, The 900 Days, p. 65

11 Geoffrey Roberts, Stalin’s Wars (Yale University Press, 1st edition, 14 Nov. 2006) p. 68

12 Evan Mawdsley, Thunder in the East (Hodder Arnold, 23 Feb. 2007) p. 50

13 Otto Skorzeny, My Commando Operations: The Memoirs of Hitler’s Most Daring Commando (Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1 Jan. 1995) p. 238

14 Mawdsley, Thunder in the East, p. 36

15 Salisbury, The 900 Days, p. 63

16 Basil Liddell Hart, A History of the Second World War (Pan, London, 1970) pp. 151-152

17 Donald J. Goodspeed, The German Wars (Random House Value Publishing, 2nd edition, 3 Apr. 1985) pp. 384-385

18 Ibid., p. 390

19 Samuel W. Mitcham, The Rise of the Wehrmacht: The German Armed Forces and World War II (Praeger Publishers Inc., 30 June 2008) p. 402

20 Salisbury, The 900 Days, p. 62

21 Ibid., p. 64

22 Ibid.

23 Mawdsley, Thunder in the East, p. 8

24 Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography (Pan; Reprints edition, 16 Apr. 2010) p. 407

25 Salisbury, The 900 Days, p. 61

26 Ibid., p. 66

Chapter III

Nazi Germany’s Economic Exploitation of the USSR

Looking back over an eight decade timespan at the design for Operation Barbarossa, the June 1941 German-led attack on the USSR, its invasion plan betrays a pathological overconfidence. The strategic planning, of advancing across a breadth of many hundreds of miles of terrain, was excessively ambitious to the point of being grotesque.

Barbarossa’s intelligence details were also poorly worked out. Nazi estimates on Soviet military capacity were based more on guesswork than reliable information, and this underestimation of the enemy would come back to haunt them.

On 13 May 1941 in preparation for the invasion, Adolf Hitler’s close colleague Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel issued an order outlining that, upon capture, all Soviet commissars were to be executed immediately. The commissars were Communist Party officials attached to military units, in order to imbue Red Army troops with Bolshevik principles and loyalty to the Soviet state.

It was because of this that Hitler designated the commissars to be liquidated in their thousands. The order signed, on 13 May, continued that Soviet civilians suspected of committing offences against the Wehrmacht could be shot, on the request of any German officer. Most maliciously of all, it was made clear that German soldiers found perpetrating crimes against non-combatants need not be prosecuted.

Those Wehrmacht officers that did not believe in Nazism, i.e. because they were monarchists or conservatives, could still reprimand German troops for misdeeds if they wished to, and this did occur. One of the most prominent German Army commanders in the early 1940s, Field Marshal Fedor von Bock leading Army Group Center, was an avowed monarchist who disliked Nazism.

The Jewish Virtual Library, overseen by American foreign policy analyst Mitchell Bard, acknowledged that von Bock “privately expressed outrage at the atrocities” committed by SS killing squads on the Eastern front; but the field marshal was “unwilling to take the matter directly to Hitler” though he did send “one of his subordinate officers to lodge the complaint”. The Jewish Virtual Library noted that the crimes committed against Soviet civilians further “outraged many of von Bock’s subordinate officers”.

This is not to suggest the Wehrmacht, as a whole, was clean in its conduct in the Soviet Union and elsewhere. It was by no means that, which came primarily as a result of staunch Nazis being placed in positions of authority in the German Army; like the Chief-of-Staff Franz Halder and Field Marshal Walter von Reichenau, commander of the German 6th Army.

Among the invasion’s goals was flagrant exploitation, looting and annexation. With this in mind, the Nazis established the Economic Office East, which was placed under the authority of Reichsmarshall Hermann Goering, the second most powerful man in the Third Reich. Goering informed Benito Mussolini’s son-in-law, Count Galeazzo Ciano, that “This year [1941] between 20 and 30 million persons will die in Russia of hunger. Perhaps it is well that it should be so, for certain nations must be decimated. But even if it were not, nothing can be done about it”. Count Ciano, who was the Italian Foreign Minister since 1936, passed on Goering’s comments to Mussolini.

More than three weeks after the German attack, Goering wrote on 15 July 1941, “Use of the occupied territories should be made primarily in the food and oil sectors of the economy. Get to Germany as much food and oil as possible – that is the main economic goal of the campaign”.

It is still not entirely clear whether the Nazi method of systematizing the plunder and administering the occupied territories (known as Plan Oldenburg) was based on the belief that the Reich required this amount of foodstuffs, with the deaths of millions of Russians and Jews from starvation being a side effect; or whether their desire was the depopulation of the conquered regions, with starvation used as a convenient process for mass murder. Whatever the principal motive, the prospects of Soviet citizens unfortunate enough to fall under Nazi occupation was grim.

The German march onto Russian soil was hardly a new historical occurrence. A generation before, the eastern divisions of the Imperial German Army, commanded by Erich Ludendorff and Paul von Hindenburg, had from late 1914 captured chunks of the Russian Empire’s territory; which on that occasion came after the Imperial Russian Army had marched into East Prussia.

German eastern expansion under Ludendorff and Hindenburg was concerned too with conquest, but theirs was more humane than Nazi policy, as it did not descend to the widespread killing of civilians or Jewish populations. Instead, Ludendorff and Hindenburg sought to commandeer livestock and horses, while exploiting “the extensive agricultural and forestry resources for the German war effort”, historians Jens Thiel and Christian Westerhoff observed.

Hitler’s East Prussian gauleiter Erich Koch, who would be in charge of ruling Nazi-occupied Ukraine, said that, “Our task is to suck from the Ukraine all the goods we can get hold of, without consideration of the feeling or the property of the Ukrainians. Gentlemen: I am expecting from you the utmost severity toward the native population”.

The 1941 German invasion force consisted of 136 divisions, which amounted to 3 million men. They were supported at the beginning by over half a million Finnish and Romanian troops, commanded by Gustaf Mannerheim and Ion Antonescu, two experienced career officers who for differing reasons desired the USSR’s destruction. Field Marshal Mannerheim of Finland, a monarchist and more moderate figure than General Antonescu, had never forgiven the Bolsheviks for shooting Tsar Nicholas II and his family on 17 July 1918; Mannerheim wept bitterly when he heard of the Tsar’s death, for he was both well acquainted with the Russian monarch and had served under him in the Imperial Russian Army.

Of the 136 Wehrmacht divisions which would attack the USSR on 22 June 1941, a modest 19 of them were panzer divisions and 14 comprised of motor divisions. In all, about 600,000 German motor vehicles would roll to the east, but the Germans deployed up to 750,000 horses in the invasion. It demonstrates that the Wehrmacht was not the ultra-modern, motorized army that Nazi propaganda insisted it was.

Facing the Germans across the border, in the western USSR, were three very large Soviet Army Groups, comprising of 193 equivalent divisions. Fifty-four of these were tank or motor divisions, significantly more than the Germans had. Since 1932, Joseph Stalin spent huge sums in equipping the military with motorized machines and heavy armor. In particular, the Russians possessed a far greater number of tanks than the enemy; but the experience and quality of Soviet tank crews was noticeably inferior to the Germans, who were battle-hardened and well-versed in the Blitzkrieg (Lightning War) style of combat.

There were other serious Russian weaknesses. Stalin’s purge of the Red Army high command from May 1937 “affected the development of our armed forces and their combat preparedness”, Marshal Georgy Zhukov wrote, the most lauded Russian commander of the 20th century. The purges, though they targeted a minority of the entire Soviet military corps, had inflicted “enormous damage” on “the top echelons of the army command” Zhukov stated. It meant that paralysis was endemic in the Red Army’s decision-making apparatus, which would have serious implications around the time of the German invasion.

Hitler’s calculations for attacking the USSR were audacious, to put it mildly. The Fuehrer expected to overthrow Stalin’s Russia in about 8 weeks, and once that was accomplished, he intended to turn back and finish off Britain. Hitler estimated that he would not really be embroiled in a two-front war and, in this he was right, for now. The British were in no position in 1941 to interfere with the Nazi plan for eastward enlargement.

The German offensive was indeed to be launched across a massive front, but the Schwerpunkt – the heaviest point of the German blow – was to land north of the Pripet Marshes in Soviet Belarus. Here, two formidable forces, Army Group North led by Field Marshal Ritter von Leeb, and Army Group Center led by Field Marshal von Bock, would implement a giant pincers movement against the Soviet armies opposing them. They would then as envisaged continue advancing and take the capital city, Moscow, European Russia’s communications hub. This indicates that Hitler had originally assigned Moscow as a primary objective.

Von Leeb’s Army Group North comprised of the German 16th Army (commanded by Ernst Busch) and the 18th Army (Georg von Kuechler), supported by four panzer divisions under Colonel-General Erich Hoepner.

Army Group Center was, by some distance, the biggest of the three Army Groups which attacked the USSR. It consisted of the German 2nd Army (Maximilian von Weichs), the 4th Army (Günther von Kluge) and the 9th Army (Adolf Strauss), bolstered by two armored groups totaling 10 panzer divisions and commanded by Generals Heinz Guderian and Hermann Hoth.

Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group South was made up of the German 6th Army (Walter von Reichenau), the 17th Army (Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel), a German-Romanian Army (Eugen Ritter von Schobert), and supported by four panzer divisions under Colonel-General Ewald von Kleist. Von Rundstedt’s Army Group was designated to advance south of the Pripet Marshes.

In doing so, von Rundstedt was expected to move rapidly in conquering eastern Poland and, specifically, to capture the ancient Polish city of Lublin, close to the Ukrainian border. This would provide a launching pad for Army Group South’s panzers to thrust into the Ukraine, and take its capital Kiev, the Soviet Union’s third largest city with 930,000 inhabitants. Thereafter, von Rundstedt’s divisions would be requested to occupy all of the Ukraine, with Hitler wanting that country’s resources for pillaging, such as wheat, for it to become “the breadbasket of the Reich”, as he put it.

While Hitler gathered his 136 divisions along the Nazi-Soviet frontier, he left 46 divisions behind to guard the rest of mainland Europe. That number does seem excessive and many of those German formations would be left idle. Military historian Donald J. Goodspeed wrote, “Certainly far fewer than 46 divisions could have countered any British initiative on the continent, a possibility that was in any case unlikely”.

Although the Soviet Army proved much larger than the Nazis thought, it was unprepared for the attack that was to come. A considerable proportion of the Red Army in June 1941 was positioned too close to the Nazi-Soviet boundary which, since 1939, had been extended across Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia and Romania.

The Stalin Line, a series of fortifications constructed from the late 1920s, and which guarded the western USSR’s pre-1939 frontiers, had merely been partially dismantled. The new forward defense positions were incomplete by mid-1941. The Soviet military’s armored formations had also been broken up, and the tanks allotted to infantry divisions. The latter error was corrected by Stalin as he repositioned the armored divisions, but they were still in the process of entering full working order when the Germans attacked.

Furthermore, Stalin and the Red Army high command believed the focal point of the German assault would fall south of the Pripet Marshes – that is through the Ukraine – whereas the Germans would, as mentioned, strike most heavily north of the Pripet Marshes across Soviet Belarus. The Russian defenses were placed at their strongest in the wrong sector of the front. This misjudgment in part enabled Army Group Center to advance rapidly into the heart of Belarus, where the Red Army was not fortified so strongly.

Sources

John Simkin, “Wilhelm Keitel”, September 1997 (Updated January 2020), Spartacus Educational Jewish Virtual Library, “Fedor von Bock (1880-1945)”

Rupert Butler, Legions of Death: The Nazi Enslavement of Europe (Leo Cooper Ltd., 1 Feb. 2004)

Goering’s Green Folder Explained, Plan Oldenburg

Jens Thiel, Christian Westerhoff, “Forced Labour”, 8 October 2014, International Encyclopedia of the First World War

Samuel W. Mitcham Jr., The German Defeat in the East: 1944-45 (Stackpole Books; First in this Edition, 23 March 2007)

Christian Hartmann, Operation Barbarossa: Nazi Germany’s War in the East, 1941-1945 (OUP Oxford; Reprint edition, 28 June 2018)

Andrei Gromyko, Memories: From Stalin to Gorbachev (Arrow Books Limited, 1 Jan. 1989)

Oliver Warner, Marshal Mannerheim & The Finns (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1st Edition, 1 Jan. 1967)

Geoffrey Roberts, Stalin’s General: The Life of Georgy Zhukov (Icon Books, 2 May 2013)

Donald J. Goodspeed, The German Wars (Random House Value Publishing, 2nd edition, 3 April 1985)

Ivan Katchanovski, Zenon E. Kohut, Bohdan Y. Nebesio, Historical Dictionary of Ukraine (Scarecrow Press; 2nd edition, 11 July 2013)

The Stalin Line, as a line of Fortified Regions, Stalin-line.by/en

Chapter IV

Why Nazi Germany Failed to Defeat the Soviet Union

As the First World War was erupting from late summer 1914, the great majority of political leaders believed it would be of short duration.

Only the rare far-sighted individual knew what was coming, such as Herbert Kitchener, Britain’s Secretary of War. At one of the first British Cabinet conferences at the conflict’s outset, Kitchener predicted the fighting would rumble on for three years, and that Britain would eventually be required to deploy its full resources (1). His estimation of a three-year war was shy of just one year.

Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary, recalled that Kitchener’s prediction had “seemed to most of us unlikely, if not incredible” (2). On 8 August 1914 Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, estimated that the war would last for nine months, which was longer than many thought.

Kitchener’s colleagues failed to realise, such was mankind’s advancements in technology by the early 20th century – about 150 years after the Industrial Revolution had begun in Britain around 1760 – that a war between the great powers would most likely be lengthy, and a slaughter of unprecedented proportions could only ensue. After the bloodletting finally stopped on 11 November 1918, realistic analysts like Vladimir Leninstated that the waging of war was “a survival from the bourgeois world”; while the German commander Hans von Seeckt said “war was no longer an intelligent way to conduct a nation’s policy”. (3)

The rise to power in Italy and Germany of fervent warmongers, Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, was a near guarantee that another large-scale conflict was in the offing.

Both Mussolini and Hitler’s taking of power, in 1922 and 1933 respectively, was assisted massively by the social upheaval and destabilisation induced as a result of World War I.

Neville Chamberlain, Adolph Hitler and Benito Mussolini Meet in 1938

The weak-willed response of the western democracies to Nazi enlargement from the mid-1930s, particularly the timid French reaction, emboldened Hitler on the path to war. British professor Evan Mawdsley, who specialises in Russian history, wrote of the Third Reich’s position by 1941 that “invading Russia was not the fatal mistake of Nazi Germany. After all, what was Hitler’s alternative? Not to invade Russia? Inaction would have allowed Germany’s enemies to become stronger, and would have left Germany economically dependent on Russia. The lethal mistake had been made earlier, when Hitler’s adventures in Czechoslovakia and Poland led Germany into a general war”. (4)

The fighting initially went as well as the Wehrmacht could have hoped for; they routed Poland in September 1939 and then scored further routine victories in Scandinavia and across western Europe, during the spring and summer of 1940. The principal opposing force, the French Army, had been decaying ever since 1917. That year mutinies spread to no less than 54 French divisions by 9 June 1917. Even in those formations where no mutinies occurred, over 50% of French soldiers returning from leave reported back drunk (5). These amazing occurrences were hushed up as best they could by the French military command, and the silence needlessly continued long afterwards.

Canadian historian Donald J. Goodspeed explained,

“Shame and pride are bad counselors, and the causes of the catastrophe in French morale that occurred in 1917 were never brought out into full daylight, where they could have been analysed and perhaps cured. That no real cure was effected, the debacle of 1940 conclusively proved”. (6)

The Nazis now turned their attention to the main target of their imperialist foreign policy: the Soviet Union, which Hitler had envisaged conquering for many years. Hitler was given encouragement by the Soviet Army’s underwhelming performance, in the 1939-1940 Winter War against Finland, with its population of around 4 million.

Yet as the Finns’ leading commander Gustaf Mannerheim fairly concluded, the Soviets learnt lessons from their opening military shortcomings on Finnish soil, and their performance “slowly improved” as the weeks elapsed (7). The gradual uptake in Russia’s military display here was unknown to the few German military observers, who had accompanied the Red Army on their Finnish incursion. The Germans were left unimpressed by the first Soviet raids, before departing homeward early.

The Wehrmacht meanwhile enjoyed more swift triumphs, over Yugoslavia and Greece in April 1941, which only emboldened Hitler further. The German conquest of Yugoslavia and Greece compelled Hitler to postpone his invasion of the USSR by 38 days. This delay is often purported to be a crucial reason, in the Nazis’ failure to capture Moscow and overthrow the Soviet Union.

American military historian Samuel W. Mitcham, who focuses largely on the Nazi regime, revealed otherwise as “the spring rains in eastern Poland and the western sections of European Russia came late in 1941, and were much heavier than usual. Many of the Polish-Russian river valleys (including the Bug) were still flooded as late as June 1; therefore, the invasion of the Soviet Union could not have begun until after that”. (8)

The ground in the western USSR had dried out by 22 June 1941. It was ideal for the panzers, half-tracks, and so on to move with ease. In addition, for weeks Joseph Stalin had refused to believe the swell of intelligence accounts he received in person from his own agencies, and from abroad, warning of a coming German attack.

Lt. Col. Goodspeed wrote,

“The reports from Soviet intelligence were the most plausible, accurate and detailed of all; and they displayed a remarkable convergence, which should have augmented their credibility. Victor Sukolov, the head of the Rote Kopelle [Red Orchestra] in Brussels, Rudolph Rössler in Switzerland, Leopold Trepper in Paris, and Dr. Richard Sorge in Tokyo all informed Stalin of Barbarossa”. (9)

The Kremlin was clearly not expecting the German invasion to fall in the summer of 1941. Marshal Nikolay Voronov, a top level Russian commander in charge of the Red Army’s artillery forces, and a future Hero of the Soviet Union, remembered on the eve of Hitler’s attack, “I did not know in that time whether we had any kind of operative-strategic plan, in case of war. I only knew that the plan for artillery and combat artillery tactics had not yet been approved, although the first draft had been worked out in 1938”. (10)

Further evidence of the lack of Russian preparedness was seen when, in the opening phase of the invasion, large numbers of Soviet airplanes were destroyed by the Germans, much of them on the ground. Air units of the Soviet Western Military District lost 740 of its 1,540 aircraft (a 48% loss) on the first day alone of the German attack (11); its local commander, General Ivan Kopets, viewed the destruction with despair and shot himself on 23 June 1941.

The ruin of the Soviet Air Force was even worse in the Baltic Military District. During the first three days of Operation Barbarossa, 920 Soviet aircraft out of a total of 1,080 were destroyed in the Baltic region, an 85% loss (12). Furthermore, many undamaged and repairable Russian planes had to be abandoned, as the Germans and their Axis allies (mainly Romanians and Finns at first) swarmed over Soviet terrain. By the first week of July 1941, the Soviets had lost almost 4,000 aircraft, while the Luftwaffe was shorn of just 550 of its planes at that point. (13)

Stalin had been awoken by his security chief, Nikolai Vlasik, in the early hours of 22 June 1941, and he was told of heavy German shelling along the Nazi-Soviet frontier. Stalin at first refused to believe that the worst had occurred and he said, “Hitler surely doesn’t know about it” (14). Later in the morning of 22 June, Stalin ordered the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov to seek out the German ambassador to the USSR, Friedrich von Schulenburg. The latter confirmed Nazi Germany’s declaration of war on the Soviet Union.

Stalin had been awoken by his security chief, Nikolai Vlasik, in the early hours of 22 June 1941, and he was told of heavy German shelling along the Nazi-Soviet frontier. Stalin at first refused to believe that the worst had occurred and he said, “Hitler surely doesn’t know about it” (14). Later in the morning of 22 June, Stalin ordered the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov to seek out the German ambassador to the USSR, Friedrich von Schulenburg. The latter confirmed Nazi Germany’s declaration of war on the Soviet Union.

A dismayed Molotov (image on the right) reported back to Stalin,

“The German government has declared war on us”. Robert Service, the British historian of Soviet history, noted that upon hearing this, “Stalin slumped in his chair and an unbearable silence followed”. When General Georgy Zhukov then suggested they put in place measures, to hold up the German advance, Service wrote “Stalin continued to stipulate that Soviet ground forces should not infringe German territorial integrity”. (15)

Contrary to what is commonly claimed, on learning that the Germans had certainly attacked with Hitler’s agreement, Stalin did not suffer a breakdown and disappear. On 23 June 1941 for example, as Service wrote in his biography of the Soviet ruler, “Stalin worked without rest in his Kremlin office. For 15 hours at a stretch from 3.20 am, he consulted with the members of the Supreme Command” (16). As the hours went by Service writes that Stalin “called generals to his office, made his enquiries about the situation to the west of Moscow, and gave his instructions. About his supremacy there was no doubt”.

Only from the early morning of 29 June 1941 did Stalin suffer a relapse, and retire to his nearby dacha in a deeply depressed condition. This was quite probably a delayed reaction brought on by his difficult visit, on 27 June, to the Soviet Ministry of Defence. When Generals Zhukov and Semyon Timoshenko showed Stalin, on operational maps, the astonishing advancements made by the German Army, Service wrote that Stalin “was shocked by the extent of the disaster for the Red Army”. (17)

Only from the early morning of 29 June 1941 did Stalin suffer a relapse, and retire to his nearby dacha in a deeply depressed condition. This was quite probably a delayed reaction brought on by his difficult visit, on 27 June, to the Soviet Ministry of Defence. When Generals Zhukov and Semyon Timoshenko showed Stalin, on operational maps, the astonishing advancements made by the German Army, Service wrote that Stalin “was shocked by the extent of the disaster for the Red Army”. (17)

Image on the left: General Zhukov

By 27 June, units from German Army Group Centre had already reached Minsk, the capital of Soviet Belorussia, and less than 450 miles west of Moscow. Shaken and disturbed by this Stalin reportedly lamented, “Lenin founded our state and we’ve f**ked it up”. (18)

After Hitler had ordered the attack against Russia on 22 June, the authorities in Britain and America forecast another brisk German victory. Their views were influenced by the apparent invincibility of the Wehrmacht, their dislike of Bolshevism, and also Stalin’s recent purge of the Red Army. Outside observers mistakenly believed the purge had decimated Soviet fighting capacity. Mawdsley in his extensive study of the Nazi-Soviet war wrote, “Many able middle-level commanders survived the purges” while the “commanders and commissars who were shot made up a minority”. (19)

A major offensive in the modern era, perhaps in any age, constitutes a huge gamble on the part of the invader, brutal as these attacks usually are, and the Nazi invasion was the most vicious of all. Various factors can combine to result in its failure: strength of the invasion force, strategic errors, quality of the terrain, underestimation of the enemy, the weather, etc. These elements are magnified when attacking the world’s largest country (Russia), as Napoleon had discovered and soon Hitler too.

Nevertheless, there are a couple of overwhelming reasons why the German attack would fail. Firstly, Hitler did not place the German nation on a Total War footing, until February 1943, much too late. The Nazi economy in the early 1940s produced an “extraordinary degree of inefficiency and wastefulness”, the English historian Richard Overy discerned (20). It resulted in labour shortages, fewer German weapons, aircraft and panzers, and less soldiers, while German women for the most part remained at home, rather than working in the armament factories.

After the defeat of France, a full mobilisation of German manpower would have produced a Wehrmacht attacking force of about 6 million men in June 1941 (21). This is double the size of the 3 million German soldiers which invaded Russia that month. Taking into account strategic mistakes committed and heroic Russian resistance, a German invasion with 6 million troops would surely have been too much for the Soviets to contend with, and it was possible to achieve.

Albert Speer, German Minister of Armaments and Munitions from 1942-1945, wrote on 29 March 1947,

“In the middle of 1941, Hitler could easily have had an army equipped twice as powerfully as it was… We could even have mobilised approximately 3 million more men of the younger age-groups before 1942, without losses in production… 3 million additional soldiers would have added up to many divisions. These, moreover, could have been excellently equipped as a result of the increased production”. (22)

Another monumental error, on the part of the German high command and Hitler, was the strategic design for Operation Barbarossa. This consisted of splitting their forces into three large Army Groups, and ordering them to capture three different objectives simultaneously (Leningrad, Moscow and the Ukraine); rather than directing their resources towards easily the most important goal – Moscow, the communications stronghold and heartbeat of Soviet Russia, which will be discussed further here.

Lt. Col. Goodspeed, a skilled military strategist, wrote that,

“Although in operations and tactics the German Army had proved itself far and away superior to the Red Army, the same could not be said of German strategy. The fault was so simple and obvious that a child might have foreseen it. The German high command had attempted too many things at the same time”. (23)

The German attack was launched across almost the entire breadth of the western USSR. Its Schwerpunkt, that is the heavy point of the German blow, fell north of the famous Pripet Marshes in Belorussia. However, the Germans and their Axis allies were ordered to attack everywhere at once. The strategic planning for Barbarossa went beyond even the Wehrmacht’s military capabilities; it was breathtaking in its boldness, irresponsible and grotesque.

Goodspeed summarised,

“But Hitler wanted too much and, as a consequence, got nothing. This same fundamental error was repeated again and again. It recurs like a leitmotif in the Führer’s strategic thought. When the advance against Moscow might have been successfully resumed in August, and previous mistakes rectified, Hitler turned his thrust south into the Ukraine and north against Leningrad. Again, two objectives and both of them the wrong ones. When Leningrad might have been taken in September, Hitler diverted forces back from Army Group North to Moscow, and thereby captured neither Leningrad nor Moscow”. (24)

This viewpoint is supported by Mawdsley who pinpointed the “mistake that Hitler and his high command made in 1941” which was “to attack everywhere” (25). Hitler did not designate primary importance to Moscow, until it was weeks too late. The Russian capital held critical significance as the centre of Soviet communications, which was recognised by military leaders like Field Marshal Fedor von Bock, the commander of German Army Group Centre, which was supposed to capture Moscow (26). Virtually all roads and railways led to the capital, like spokes into the hub of a wheel.

This was not the case when Napoleon’s forces had occupied Moscow on 14 September 1812. Moscow at that time did not hold the same status, by comparison to its importance in the 20th century, when armies had become reliant on railways and motorised transport for supplies. The first railway line in Russia was built in 1837, a quarter of a century after Napoleon’s invasion.

Were Moscow to be captured in the autumn of 1941, the Russians would have had tremendous difficulty supplying and reinforcing their northern and southern fronts (27). This includes the Leningrad and Ukrainian sectors. The rail system of the western USSR would have been shattered, inflicting a hammer blow on the Soviet Army.

Goodspeed wrote that from Barbarossa’s outset,

“Quite conceivably, a single great thrust along the Warsaw-Smolensk-Moscow axis might have secured the Russian capital for the Germans by the end of August. Army Groups North and South could have acted as flank guards for such a thrust, and once the Russian centre had been demolished and the communications hub of Moscow taken, the Soviet northern and southern fronts would have been isolated from one another. Then a drive down the Volga in September might well have achieved a second victory, greater even than the Battle of Kiev. This done, Leningrad and the northern front could have been dealt with at leisure, and by another overwhelming concentration of force”. (28)

One major thrust towards Moscow would, also, have taken the ferocious Russian weather out of the equation. The autumn rains and snow arrived in force from early October 1941, weeks after Moscow could have been taken. As events panned out, such weather seriously slowed the German advance.

The political ramifications of Moscow’s capitulation would have been considerable too. Stalin and his entourage were headquartered there. What would Stalin have done had Moscow fallen to the Germans in August or September 1941? He may have decided to stay and thereby seal his fate, or he could have chosen to relocate to Asiatic Russia, where it would have been arduous to hold together a government.

Most importantly of all, as Germany’s generals were aware, the bulk of the Red Army was centred in front of Moscow for the defence of the capital. If these Russian divisions were to be surrounded in a vast pincers movement and forced to surrender, the war would have been practically over. (29)

Two months into the invasion, on 21 August 1941 Hitler fatefully intervened in the direction of the war, believing he would be proved right and the German generals wrong – as had been repeatedly the case on political matters. Hitler compounded Barbarossa’s early strategic mistakes by ordering on this date: “The most important objective to be taken before the coming of the winter is NOT the capture of Moscow, but the capture of the Crimea and of the industrial and coal-mining area of the Donets, and the cutting off of Russian oil supplies from the Caucasus; and to the north the investment of Leningrad and the linking up with the Finns”. (30)

Hitler’s Chief of Operations, General Alfred Jodl, defended this decision by claiming that Hitler wished to avoid the blunders of Napoleon (31). As mentioned earlier, Moscow was of much greater importance in the year 1941 as opposed to 1812. Hitler was greedy and saw too many things at once, rather than focusing on a single goal at a time (similar strategic errors were committed in July 1942, when Hitler split up his forces to capture two objectives simultaneously, Stalingrad and the Caucasus).

Hitler’s wish, to strike everywhere, could have been influenced too because of his desire to spread as much death and destruction to the Soviet Union as possible, which he believed was the homeland of “Jewish Bolshevism”.