History of World War II. Britain – Adolf Hitler’s Star-crossed Love

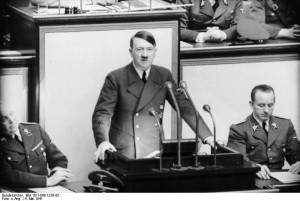

Two weeks after Britain’s treacherous attack on the French navy, the world was already discussing a very different event. On July 19, 1940, Adolf Hitler stepped up to the podium of the German Reichstag. In that hall sat not only the members of the German parliament, but also generals, the leaders of the SS, and diplomats – the cream of the Third Reich. They all eagerly listened to their Führer. And what was he speaking about? About the brilliant success of the German army that had crushed France with such unbelievable speed. But then Hitler spoke again … about peace. Not about the abstract idea of “world peace,” but about a very particular type of peace with the world power that embodied that ideal. Hitler, an Anglophile, was at the peak of his celebrity when he made his peace overture to Great Britain. The victor was offering peace to the vanquished. Hitler’s speech, which was being translated into English by an interpreter as he spoke, flew around the world.

From Britain I now hear only a single cry – not of the people but of the politicians – that the war must go on! I do not know whether these politicians already have a correct idea of what the continuation of this struggle will be like. They do, it is true, declare that they will carry on with the war and that, even if Great Britain should perish, they would carry on from Canada. I can hardly believe that they mean by this that the people of Britain are to go to Canada. Presumably only those gentlemen interested in the continuation of their war will go there. The people, I am afraid, will have to remain in Britain and . . . will certainly regard the war with other eyes than their so-called leaders in Canada.

Believe me, gentlemen, I feel a deep disgust for this type of unscrupulous politician who wrecks whole nations. It almost causes me pain to think that I should have been selected by fate to deal the final blow to the structure which these men have already set tottering… Mr. Churchill… no doubt will already be in Canada, where the money and children of those principally interested in the war have already been sent. For millions of other people, however, great suffering will begin. Mr. Churchill ought perhaps, for once, to believe me when I prophesy that a great Empire will be destroyed – an Empire which it was never my intention to destroy or even to harm…

In this hour I feel it to be my duty before my own conscience to appeal once more to reason and common sense in Great Britain as much as elsewhere. I consider myself in a position to make this appeal since I am not the vanquished begging favors, but the victor speaking in the name of reason.

I can see no reason why this war must go on. (William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, p.677)

On July 22, 1940, the British foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, made a speech rejecting Hitler’s call for peace. This country so idolized by Adolf Hitler, this world power, this alliance that he regarded as exceptionally promising and useful to Germany, had once again rebuffed his outstretched hand. It was a dead end. Not for the German state, which had paid such a small price to become so powerful. It was a dead end for the politician Adolf Hitler, who passionately longed to destroy communism and to build a new world power, but who had instead signed peace treaty with the Bolsheviks and was battling those who had built an exemplary empire long before he had been born. An empire that Hitler himself had always idealized. “I admire the English. As colonizers, what they have accomplished is unprecedented,” noted the Führer in one of his many statements about the virtues of British colonialism.

But what about Operation Sea Lion? What about the merciless bombing of London? What about the Battle of Britain that was waged in the skies? Can all that not be seen as proof of the English fight against the Nazis and of Hitler’s desire to conquer the British Isles?

No, it cannot. That whole “fight” was merely one small episode compared with the subsequent bloody drama in the East.

Let’s start at the beginning. On July 13, 1940, six days before his “Peace” speech in the Reichstag, the Führer issued Directive No. 16: “to develop plans against the British.” This directive opened with the statement, “England, in spite of the hopelessness of her military position, has so far shown herself unwilling to come to any compromise.”[1] Aware of Hitler’s deferential attitude toward the British and his extreme reluctance to fight them, the German generals did not put a great deal of effort into drafting Operation Sea Lion. They were confident that no German troops would ever land in England. German General Gerd von

General Gerd von Rundstedt

Rundstedt told Allied investigators in 1945 that “the proposed invasion of England was nonsense, because adequate ships were not available … We looked upon the whole thing as a sort of game … I have a feeling that the Fuehrer never really wanted to invade England.”[2] His colleague, General Günther Blumentritt, also affirmed that among themselves, the German generals considered Operation Sea Lion to be a bluff. [3] Proof of this was Hitler’s decision to disband 50 divisions and transfer another 25 to the peacetime corps.[4]

In August 1940, the American journalist William Shirer arrived on the shores of the Channel and found no signs of preparation there for any invasion of the British Isles.[5] Even Hitler’s deadlines for readying the German army for an attack on England were pushed back from Sept. 15 to the 21st, then to the 24th, and finally to Oct. 12. But instead of an order to land, a very different document materialized on that same day: “The Fuehrer has decided that from now on until the spring, preparations for ‘Sea Lion’ shall be continued solely for the purpose of maintaining political and military pressure on England.”[6]

So in what light should we view the famous Battle of Britain? Why did Hitler give the order to begin actively bombing the Isles? In order to properly grasp Hitler’s strategy one must first understand his objectives. He has no desire to fight England, but the British Empire refuses to sign a peace treaty. What is the leader of Germany to do in such a situation? Either accept the English conditions (which would be a stupid and entirely unacceptable concession for any victor to make) or try to persuade them to make peace. But he wanted only to persuade, not to crush or destroy them. Because even if German troops successfully landed on English shores, this would be of little use to Hitler. If the Isles were occupied, Britain’s royal family and aristocrats would simply hop onto warships and head for Canada, without surrendering or signing a peace treaty. And what then? The war ahead looked endless for Germany, because, as we have said, the Germans had virtually no navy. What good would it do them to occupy England? No good whatsoever. But Hitler clung to his shreds of hope that by making a big show of preparing to storm British shores and by playing up the horrors of a war on English soil, he could induce the British leaders to acquiesce to a peaceful compromise. If only he could use bombs and bluffs to make the British see that their pigheadedness would have serious consequences! To accomplish this, he would begin Operation Sea Lion with an air attack over the Isles – he would launch the Battle of Britain.

We are always enthralled by myths and stereotypes. Ask anyone – who was the first to bomb civilian cities? And you’ll hear – “the Nazis.” But in fact, the first bombs – and they landed on civilian, not enemy, targets – were not dropped by German planes but by British. On May 11, 1940, just after becoming prime minister, Winston Churchill ordered the bombing of the German city of Freiburg (in the province of Baden). It was not until July 10, 1940 that German planes conducted their first raid over British soil. That date marked the onset of the Battle of Britain.

For the most part during the Battle of Britain, German flying aces attacked enemy military targets. But the British alternated raids on military objectives with air strikes against German cities. On Aug. 25, 26, and then the 29th, British planes shelled Berlin. Speaking in his besieged capital on Sept. 4, 1940, Adolf Hitler spoke specifically about this air campaign, “… Whenever the Englishman sees a light, he drops a bomb … on residential districts, farms, and villages. For three months I did not answer because I believed that such madness would be stopped. Mr. Churchill took this for a sign of weakness. We are now answering night for night.”[7]

Only on Sept. 7 did German planes begin regular raids on London. This, incidentally, is still more clear evidence that Hitler was not planning an invasion of the British Isles. Otherwise, turning his attention away from neutralizing British air power and instead beginning retaliatory raids on civilian targets looks like complete idiocy. If German leaders were preparing to occupy England, they would not have been bombing the British capital – instead they would be destroying the airfields and military installations that would hamper any invasion by the German army.

We are constantly faced with one inescapable fact: the leader of Germany is waging only a half-hearted war on Britain, merely reciprocating with counter attacks. That’s not how you win a war. But Hitler wasn’t planning to win that war, he was planning to end it!

Centre of Coventry, UK after German air raid, November 1940

How deadly and terrifying were those German air raids? According to the official numbers, during the Battle of Britain 842 people were killed in London and 2,347 injured.[8] The most infamous German air strike on the English town of Coventry on Nov. 14, 1940 killed 568. Obviously the death of any human being is a tragedy, but these numbers seem diminished when compared to the millions of Russian, Chinese, Yugoslavian, and Polish victims of World War II. Something similar happens when one looks at the total British contribution to the defeat of Nazi Germany. Over the course of the entire Second World War, England lost 388,000 people, including 62,000 civilians. [9] This means that only 62,000 British noncombatants fell victim to German bombs throughout all of WWII. So, is that a lot or a little? Everything is relative. The French territory occupied by the Germans was not the primary target of Allied planes. For that reason, British and American bombs killed only 30,000 people there, over the course of four years (from the summer of 1940 to the summer of 1944). But after the invasion of Normandy, British and American planes began pounding French cities and villages far more frequently, in order to rout the German forces. As a result, during the three months of summer in 1944, as the Germans were being driven from France, another 20,000 French were killed (out of a total of 50,000) by bombs dropped by their “liberators”.[10]

But the number of German civilians who died in bombing raids is still shrouded in mystery. No one can give a final figure. Because it is too horrifying. If Germany had won WWII, then Churchill, Roosevelt, and the chiefs of the Allied air forces would have been guaranteed not only a seat in the dock, but also a death sentence for their hundreds of thousands of victims. But history is written by the victors. Therefore, other criminals were tried for other crimes at Nuremberg, while those who wiped out entire German cities along with all their inhabitants were able to retire in peace …

A section of Hamburg lies in ruins in 1946. It took years to rebuild Hamburg and the other German cities devastated by Allied bombing raids during WWII.

Hamburg was the first victim of Britain’s aerial warfare strategy. Operation Gomorrah began on the night of July 24, 1943. The British had launched previous attacks on German cities. But much was novel about this air campaign: both the number of bombers (700) as well as the astonishing number of firebombs that were dropped on the city. And so a new and terrible phenomenon was introduced into human history – the firestorm. When a large number of small fires are concentrated in one place, they very quickly heat the air to such a temperature that the cooler air surrounding the fire is sucked, as if through a funnel, into the space around the source of the heat. The difference in temperature reached 600-1,000 degrees, and this formed tornadoes unlike anything seen in nature, where temperature differences are no more than 20-30 degrees. Hot air whipped through the streets at high speed, carrying sparks and small pieces of burning wood, igniting new buildings and literally incinerating anyone caught in the firestorm’s path. There was no way to stop this cyclone of flames. Fire raged in the city for several more days, and a column of smoke rose to a height of six kilometers!

Phosphorus bombs were also used against the inhabitants of Hamburg. Phosphorus particles stick to the skin and cannot be extinguished because they reignite as soon as they are exposed to air. The city’s residents were burned alive and there was no way to help them. Eyewitnesses claim that the street pavement bubbled, sugar stored in the city’s warehouses boiled, and glass windows melted on streetcars. Innocent civilians were burned alive, turned into ash, or were suffocated by poisonous gas in the basements of their own homes as they tried to find refuge from the bombs. As soon as those fires were put out, a new air raid would come, and then another. In one week, 55,000 residents of Hamburg died in air strikes, which is almost the same number as were killed in England throughout the entire war.[11]

Dresden on the eve of WWII

Have you ever been to Hamburg? If you go, you might wonder why nothing from the old Hanseatic city remains. And if you ask they’ll tell you that 13 square km. of the historic city center was completely incinerated; 27,000 residential and 7,000 public buildings were destroyed, including some ancient monuments of culture and architecture; and 750,000 out of Hamburg’s population of two million were left homeless.

But that was only the beginning. The second firestorm in human history was created in the city of Kassel, on Oct. 22, 1943. On that night, 10,000 residents died in that city of 250,000. Kassel would be followed by Nuremberg, Leipzig, and many other towns. Sixty-one German cities with a total population of 25 million suffered colossal damage, eight million were left homeless, and about 600,000 were killed. Among them were many children, the elderly, and women, but very few men. After all, most of those were at the front …

The worst firestorm was inflicted on Dresden by British and American air bombers. British planes carried out the first raid on the night of Feb. 13, 1945. The next morning the flaming city was subjected to a second offensive – this time courtesy of the US Air Force. In all, 1,300 bombers took part, resulting in a firestorm of unprecedented magnitude. Dresden was wiped off the map. Once considered one of the most beautiful cities in Germany, it is today a city almost devoid of architectural charm. It has never been possible to definitively establish the number of victims who died: according to various estimates, between 60,000 and 100,000 people perished in a fiery hell. Look at the date of the raid and ask yourself, why, two months before the end of the war, when the end was already clear, was it necessary to necessary to unleash such slaughter in a city with no military targets or weapons factories? Was this an accident? An error? Remember who it was who dropped nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the final days of World War II. Those criminals were never punished either.

The bombing of civilian cities resulted in destruction and loss of life in all the belligerent countries. It is extremely difficult to determine which side was the first to launch such attacks. But British bombs of course were responsible for the most victims and greatest devastation.

ORIENTAL REVIEW publishes exclusive translations of the chapters from Nikolay Starikov’s documentary research ““Who Made Hitler Attack Stalin” (St.Petersburg, 2008). Mr. Starikov is Russian historian and civil activist. The original text was adapted and translated by ORIENTAL REVIEW.

Notes:

[1] Peter Fleming. Operation Sea Lion: Hitler’s Plot to Invade England. Pg. 15.

[2] William Shirer. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Pg. 761.

[3] Ibid.

[4] A. J. P. Taylor. Vtoraya Mirovaya Voina // Vtoraya Mirovaya Voina: Dva Vzglyada. Pg. 423.

[5] William Shirer. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Pg. 761.

[6] Ibid. Pg. 774.

[7] William Shirer. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Pg. 779.

[8] Ibid. Pg. 780.

[9] Alan Bullock. Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives. Pg. 983.

[10] Charles de Gaulle. Voennye Memuary. Edinstvo. 1940–1942. Pg. 189–190.

[11] Janusz Piekalkiewicz The Air War, 1939-1945. Harrisburg, Pa.: Historical Times Inc., 1985. Pg. 288.

PREVIOUS EPISODES

Episode 16. Who signed death sentense to France in 1940?

Episode 14. How Adolf Hitler turned to be a “defiant aggressor”

Episode 13. Why London presented Hitler with Vienna and Prague

Episode 12. Why did Britain and the United States have no desire to prevent WWII?

Episode 11. A Soviet Quarter Century (1930-1955)

Episode 10. Who Organised the Famine in the USSR in 1932-1933?

Episode 9. How the British “Liberated” Greece

Episode 7. Britain and France Planned to Assault Soviet Union in 1940

Episode 6. Leon Trotsky, Father of German Nazism

Episode 5. Who paid for World War II?

Episode 4. Who ignited First World War?

Episode 3. Assassination in Sarajevo

Episode 2. The US Federal Reserve