History of the British Empire: How the Mughals Viewed the British

Establishment historians portray the British Empire in India as a testament to British industry, British values, British discipline and general British superiority over the native people. They also credit the British with the creation of modern India, implying that the civilization and economy of pre-British India was superseded by the “natural” rules of evolution and survival. The following is a view from the other side. From 17th Century Mughal India, where the British East India Company had just set shop, and had instantly gained notoriety for rapaciousness. English translations of authentic Mughal-era Persian documents give an interesting view of Mughal tensions with the British at Bombay. They shed light on the Mughals mistaking British economic terrorism for “trade.” A grave mistake which lead to the colonization of India.

The Background

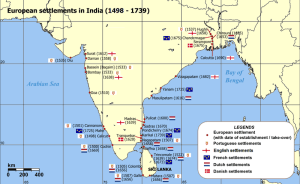

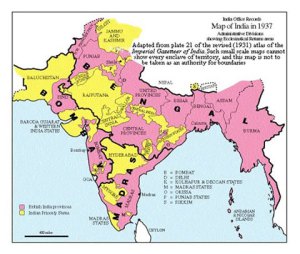

The incidents about to be described take place in a historical context best understood by the following maps.

The Mughal Empire is at its political zenith, under the last of the Major Mughal Emperors, Aurangzeb.

The British are one of the many European nations who have set up trading posts in coastal areas. Note that this map only shows European settlements. Whereas other Asian and Middle Eastern countries also had trading posts and settlements.

After being granted official permission to trade with India in 1612, British had created several settlements and trading posts across India. To quote,

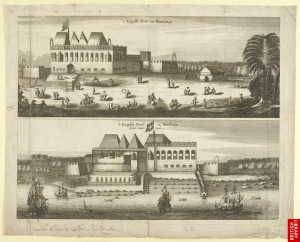

The company created trading posts in Surat (where a factory was built in 1612), Madras (1639), Bombay (1668), and Calcutta (1690). By 1647, the company had 23 factories, each under the command of a factor or master merchant and governor if so chosen, and had 90 employees in India. The major factories became the walled forts of Fort William in Bengal, Fort St George in Madras, and the Bombay Castle.

Pretty soon, the British trading post at Bombay transformed into a walled fort which became known as the Bombay Castle.

Note the location selected for Bombay Castle, which would be definitely hard to control by the Mughals, who lacked a well-developed navy. The British clearly had imperial ambitions from the very beginning. On the other hand, genuine “traders” from other Asian countries never bothered to dig themselves into castles.

Approximately two centuries later, the British had crawled out of their “Trading Posts” to become the defacto Emperors of India.

Deconstructing the Establishment Narrative requires an understanding of the several myths that Establishment Historians employ.

Myth#1: That the British represented a Superior Economy and Superior Industry:

The very fact that the British would undertake a long, circuitous and risky route around Africa (this was before the Suez Canal) to establish “trading posts” in India indicates that the real action was in India. The British had thankfully been prevented from digging into the economic growth of the subcontinent because of the Ottomans who had blocked European land routes to India. But with the development of maritime technologies, the British found their way. Once the British managed to control India though, they did develop a superior economy based on machines (The “Industrial Revolution” of Manchester, which is covered in one of my books). Machines compensated for their lack of skilled workers. And initial British economic growth was from forcing finished British products upon the captive economy of India, which would eventually devolve into a “third world country.”

As we shall see in the documents below, the British excelled at (and still do) in creating parasitic bureaucratic structures which enabled them to extract taxes, customs, duties etc. from areas whose economic growth was completely inconsequential to their presence. Once the British Empire was established in India, they would even levy taxes on cooking salt! And opposition to this tax became a focal point of Gandhi’s movement. Needless to say, such parasitic behaviour had destructive consequences in the longterm. And the India that the British left behind is a good example.

At a time when the Indian economy was a level playing field, genuine traders such as those from Asian and Middle Eastern countries were busy getting their hands full. They were not digging themselves into island-castles like the British. While the British also had their hands full with legitimate trade, the documents we shall examine below reveal that they were secretly using the Bombay Castle to conduct economic terrorism (piracy).

Myth#2: That the British represented an Egalitarian Society:

When it comes to caste-based societies, India first comes to mind. But upon closer examination of British society, especially of that period, was so strongly hierarchical that it can be compared to a caste system. However, there are strong differences from a formal caste system as that in India.

- The top “caste” of British society, i.e. the Illuminati, established itself in Britian through conquest. They are of Germanic-Dutch origin.

- The top “caste” of British society is completely closed to assimilation or association.

- The top “caste” of British society is undocumented, and remains hidden from public view (with the exception of official royalty).

- The top “caste” of British society, i.e. the Illuminati, is probably the most predatory cabal in the creation. They are not just content with gobbling the privileges and prerogatives of their subject populations, but seek to establish the same dysfunctional societies even in non-Western countries.

- The lower castes are fairly content with their position as surrogates. In fact, they become the most efficient surrogates the world has ever seen. Revolution and rebellion are unheard of. Even Guy Fawkes, who stood up to the top caste, is portrayed as a terrorist. Robin Hood has been forgotten. The lower castes are more than content with being given some kibbles and bits from the larger spoils obtained by the top caste. And they will happily cheerlead any venture the top caste engages in. Needless to say, they are often exposed to risks, and even death. While their high caste royals, directors and commanders always remain safe.

- The lower castes cannot “escape” their fate unless they are to completely cut off contact with British society. But given their philistine nature, they have little regard for other societies and therefore fall back on their own ones, creating a cycle of servitude. Their fate is also sealed by the fact that their high caste has absolute domination over all geographical regions of their country.

- Actual slavery existed among the lower castes, with entire generations of orphans and other vulnerable members of society being reared for the sole purpose of providing cheap labour for enterprises of the higher castes.

- Outsiders (non-Britishers) are simply not allowed to participate in British economy. They cannot settle, compete or trade in Britain. Non-Europeans such as Indians are especially discriminated as “heathen.” While practicing such racist exclusivity in their home country, the British had no issue taking ungrateful advantage of the tolerance that was a feature of the Indo-Islamic civilization, to invite themselves to the Indian subcontinent.

Needless to say, 17th Century India was far more egalitarian than the then British Society. The servitude of the British people to their Criminal Elite was a phenomenon the people of the subcontinent could not relate to. Neither was attention ever drawn towards it in popular media. And the people of the subcontinent would later try to apologetically define this curious phenomenon in terms of British “values” of “loyalty,” “Protestant work-ethic” and “discipline.” But it was none of these labels.

Myth#3: That the British succeeded in India because of Superior Technology

By then, the British did have superior technology in some areas, such as naval expertise and gunpowder weapons. But so did Germany and many other Western nations. And these technologies were only critical in some aspects of the British conquest of India. For example, the British did not have the numbers or the resources to take on Indian armies.

If we look at British conquest of India, we find it unusual compared to other conquests of India. For example, the Mughals came to India storming down the mountain passes of Central Asia with a massive gunpowder army, and conquering the city of Delhi in what can be described as a very risky gamble.

The British did none of that. They were fairly averse to high-stake gambles.

What did they do then? Establishment historians will give various answers. Some will even say that with Mughal power waning, British ascendency was only natural, and therefore we need not think too much about it.

A fresh look at British leadership, the Illuminati, may give us a radical answer. As readers may be aware, the Illuminati tends to be associated with unnatural, satanic malevolence towards the human species. What do you get when you combine the malevolence the Illuminati with the extraordinary and unquestioning servitude of the British people? The British Empire?

Clearly, the Mughals were no match for the sophisticated economic terrorism of the British Empire, a phenomenon which was completely alien to their then socio-political context. Further, the British had the secret blessings of all Western countries, which by then had succumbed to the same Illuminati. What else can explain traditional foes such as the French and the Portuguese, quickly abandoning their pretensions for India once it had been (secretly) decided that the British were to prevail?

The Documents

An account of the Mughal assault on the Bombay Castle

In 1686, the British East Company not content with being granted permission to operate trading posts in Bengal, entered the waterways of Bengal with twelve warships, carrying 200 pieces of cannon and 600 men. They intended to seize the port of Chittagong from the Mughals. The British encamped on a marshy island on the mouth of the Hooghly river. Soon, half their force was wiped out by disease. Overconfident that the Bombay Castle on the West Coast could not be breached by Mughal forces, the British began blockading Mughal ports on the West Coast in 1688. Ships carrying pilgrims to Mecca were also captured. After that, Emperor Aurangzeb issued orders for the extirpation of the British from all of India, and for the confiscation of their property. In accordance with this, an assault was ordered on the Bombay Castle.

The following account is by Abul Fazl Mamuri, a Mughal historian who wrote during the reign of Aurangzeb (1658-1707). It is found as an Appendix in book which is the English translation of the Persian account of another historian who was also witness to Aurangzeb’s reign, Khafi khan (more about him later). Note that the date of the account may be slightly incorrect. Should you wish to cite this account, please use the following citation (given in MLA style):

Khafi Khan, Aurangzeb in Muntakhab-al lubab trans. Anees Jahan Syed (Bombay: Somaiya Publications, 1977)

Page 371

Appendix A

Siddi Yaqut’s Siege of Bombay

(Ma’muri British Museum Or. MSS. 1671, 159a-160b and A.T., pp. 468-473)

Another event of the twenty-seventh regnal year [of Aurangzeb] (August 24, 1683-4), was the effort made by Yaqut Khan, the Abyssinian (Habashi), the faujdar of Rajpuri to conquer the island of Bombay which belonged to the English – efforts which owing to the lack of attention on the part of the officers of the court were quite wasted. This is a brief account of it.

The English though Christians, have a king Of their own, quite distinct from the king of the Ferangi (Portuguese); their places of worship and churches are also not like those of the Ferangis. A long time ago they had captured an island near Rajpuri and on the way to the port Of Surat, and building a strong fort there, had gjven it the name of Mamba-i [1] (Bombay). Here they had established officers who consider themselves the representatives and delegates of the king of their nation; their gumashtas have factories (Koth-i-tijarat) at

[1] It is a very old city on the islands of Mahim and Mumba Devi, the two islands now combined make the present city of Bombay. Under Aurangzeb the town was held by the English under the sovereignty of the English monarch. A silver rupee first of its kind was minted at Bombay “by Authority of Charles the Second, King of Britain, France and Ireland” (Hobson Jobson, pp. 775-776). For a discussion on the origin of the town and history see Ibid pp. 102-104.

Page 372

Surat and other ports, and their ships frequent all sea-ports.

After the Marathas had established their power over and and sea, the mischief-makers of Sorath (Saurashtra) known as Jaro(?) in the province of Ahmadabad began occasionally to plunder the ships on the way to Bhakkar and Iran. Following them, the English, owing to the strength of their fort and some warboats, in the twenty-seventh year of the reign when Mukhtar Khan was the mutasaddi of the Surat fort, seized a ship of Mulla Abdul Ghafoor, one of the leading merchants of Surat; this ship, after selling the merchandise of India was returning from the ports of Mokha and Jaddah, and it had no valuables on board except Ibrahimi coins, silver and gold. They used the silver and Ibrahimis for minting their own coins, which they caused to circulate in their fort and their islands.

When the vakil of Mulla Abdul Ghafoor petitioned to the emperor, the latter ordered Mukhtar Khan to investigate the matter. Mukhtar Khan wrote to the English, but the English denied their responsibility and attributed this boldness to the inhabitants of Sorath in the province of Ahmadabad. Mukhat Khan thereupon, imprisoned the English gumastas, who were in the port of Surat. The English on coming to know of this, captured another ship of Mulla Abdul Ghafoor, which was going to one of the ports, on the high seas; they brought it to the fort and kept it in their custody without unloading it. They then wrote to Mulla Abdul Ghafoor. “Unless our gumastas, who have been imprisoned without any proof of guilt, are set free, we will not let go of your ships.” The English also wrote a letter to Siddi Yaqut requesting him to appeal to Mukhtar Khan that their gumastas may be set free.

Siddi Yaqut Khan, who in that region had obtained a great reputation for good administration and courage, also knew all the mischief-makers of the region. In reply to the English request, he wrote a few harsh words of warning. The English after a few days, captured twelve boats full of grain and other commodities belonging to Siddi Yaqut, which were coming from some place.

Siddi Yaqut realised that the English were beating the drum of rebellion and began to reflect on the measures for punishing them. He consulted Siddi Ambar and Khusrau Khan, who were his friends and comrades. It was impossible to undertake the enterprise without the English coming to know of it; the fort of Bombay was strong and (the garrison) well-organised; the way from Rajpuri to Bombay is across the sea and the branch of sea for two or three karohs (runs through the land) and the whole of it is within the range of cannon-shot from the shore. The English had established their chowkies on both sides of this sea-way and were on the watch both day and night; they also took customs duties from boats full of grain etc. that passed through this sea-way. It was impossible for (enemy) war-boats to cross this narrow channel, and there was no other route.

After some laborious planning Siddi Yaqut and Siddi Ambar proceed with the siege, which is described in page 373. The following page (374) details the narrowly missed victory.

Page 374

After a period of two months, the trenches and the mines reached the foot of the fort. Owing to the continuous fire from the artillery of the fort, the followers of Yakut Khan were reduced to sore straits, and many of his most courageous officers gave way to despair. But Yaqut Khan, in order to encourage his men to an onslaught , pushed himself forward against many thousand (English) muskets that were being discharged; most of the men who were with him at his right and at his left, bowed their heads low in martyrdom and did not raise them again. But the Abyssinian leader, who had reached the age of eighty, did not stir from his place, and keeping his feet firm, he looked fiercely at those who had not advanced and shouted to those who were lingering behind the corpses.

Two or three thousand soldiers of Siddi Yaqut were wounded or martyred on that day. , but the courage of Yaqut Khan had been such that the fall of the fort was a question of that day or the morrow. At this moment, the vakils of the English approached the officers of the court by spending three lakhs [3,00,000] and represented. “The English are not to blame. We promise that forsaking the fort, we will live in a haveli built of wood outside it.” The request of the English was accepted and stern mace-bearers were dispatched to keep Siddi Yaqut away from the foot of the Bombay fort. When they reached the conditions described, Siddi Yaqut refrained from persisting in the siege of the fort, but he objected to starting for Rajpuri, as owing to the rainy season, it was difficult for boats to navigate in the storm-tossed sea. But the mace-bearers immediately put him on his boats and compelled him to start for Rajpuri. Two boats full of his valuables were sunk [2]. After commenting upon the religious and egalitarian ways of Siddi Yaqut and his struggle with the Marathas, Ma’muri adds] “The Abyssinians had gained such a predominance over the Marathas that Sambha was afraid of the name of the Abyssinians. But after the disgrace to which he was put in the siege of Bombay, Siddi Yaqut neglected reducing the fort built by the Marathas on the islands, which would have entailed the expenditure of a lot of money and siege material.

[2] Two words here are not clear in both the MSS (A.T., & British Museum).

Why did the Mughals mysteriously abandon the siege despite the effort expended, and when victory was only a matter of time?

Why did the Mughals mysteriously abandon the siege despite the effort expended, and when victory was only a matter of time? This continues to remain a mystery. But in one of my books, I did find indication of Illuminati infiltration within Mughal royalty. Looks like the British made use of some inside help to circumvent Aurnagzeb’s orders to extirpate the British. Later, in the 39th regnal year of Aurangzeb, Sidi Yaqut barely survived a well-coordinated assassination attempt, which was attributed to the wife Khayriyat Khan, although her motives remain a mystery (Khafi Khan, History of Alamgir, p.449).

To make Aurangzeb lift the siege of Bombay Castle, British East India Company executives begged for his pardon while prostrating themselves before him. They also agreed to pay a huge indemnity, which was immediately delivered to the Mughals. Source: ebay, July 2004 “Title: “LES ANGLOIS DEMANDENT PARDON A AURENGZEB QU’ILS ONT OFFENSE”: from “Histoire Philosophique et Politique Des Establissemens et du Commerce des Europeens dans Les Deux Indes”, by Guillaume Thomas Raynal, published in Geneva, 1780.”

Mughal admiral Siddi Yaqut operated the Mughal Navy out the island fortress of Murud-Janjira on the West coast. It was the only fort along India’s Western coast that continued to remain undefeated despite Dutch, Maratha and English East India Company attacks.

An account of the British in Bombay Castle resuming economic terrorism piracy against Mughal ships

The Mughals made a dangerous mistake by lifting the siege of Bombay in 1690 after the British begged for peace.

Had Aurangzeb persisted in extirpating the British from India, the entire course of subsequent history would have been a much positive one.

Five years later, the British would dishonour the peace treaty they had concluded with Aurangzeb by capturing a Mughal Imperial ship returning from Mecca. But this time, they learnt the neccesity of being sneaky. Although the operation was conducted out of Bombay Castle, the British created plausible deniability by attributing it to British “pirates.”

The following is an English translation of the account of another historian who was also witness to Aurangzeb’s reign, Khafi khan. Unlike Mamuri, Khafi Khan was not a court historian. And therefore his accounts are considered more insightful and unbiased. Note that the page numbers found within the paragraphs refer to the page numbers of the original Persian manuscript. Should you wish to cite this account, please use the following citation (given in MLA style):

Khafi Khan History of Alamgir trans. By S. Moinul Haq (Karachi: Pakistan Historical Society, 1975)

Page 419

English Pirates create trouble

The story of the trouble created by the English at sea, and the expedition of Sidi Yaqut to the fort of Mumbi (Bombay) has already been narrated. He had to discontinue the operations under orders of the Emperor just at the time when he was about to capture it. In this year, the Imperial ship, named Ganj-i-Sawa’i, the largest in the fleet at the port of Surat, which used to take pilgrims every year to House of God was returning to Surat with fifty-two lakhs [52,00,000] of cash in the shape of gold coins and Riyals[1], the sale proceeds of Indian goods Mukhkha[2] and Jedda. The captain of the ship Muhammad Ibrahim considered himself to be a great warrior. He had got prepared the iron ladles and kept them, with him, and used to say that [P. 422] he would capture with their help the ships of the enemy and their men alive. There were eighty guns and four hundred muskets, besides other armaments on the ship. When the ship was at a distance of eight or nine days journey from the port of Surat, an English ship, which was very small compared to it and had not even one third or one fourth of its

[1]: The name of Arabian coins.

[2]: Mukhkha (Mocha), a small sea port near the strait of Bab-al-Mandab, famous for the export of copper.

Page 420

Armaments came forward to fight it. When it reached within gunshot distance, they fired a gun from the Imperial ship. Unfortunately for the men in the ship the gun burst and three or four persons were killed by the pieces of iron that flew from it. In the meantime, a ball from the enemy’s ship struck the central mast of the Ganj-i-Sawa’i, which is called Daol, in the language of the sailors and on which mainly depends the safety of the ship. The ship was damaged. On coming to know of this the men on the English ship, became bolder and brought it close to the Imperial ship and attacked it. They started fighting with their swords and jumped into it. The Christians were not as skilled in sword fight as the Muslims are and there was so much armament on the Imperial ship that if its captain, had shown some courage, he would have freed himself from the trouble, but as soon as the English boarded the ship, Muhammad Ibrahim, the captain, who was also the Fawjdar of the ship rushed to the space under the planks of the deck. Some Turkish maids whom he had purchased at Mukhkhah and kept them as his slave girls (Sariyyah), and tied turbans on their heads, gave them swords and asked them to fight, but they fell into the hands of the Christians. The whole of the ship came under their control and they carried away all of the gold and silver, along with a large number of prisoners to their ship [P.423]. When their ship became overloaded, they brought the Imperial ship to the sea coast, near one of their settlements. After having remained for a week, in searching for plunder, stripping the men of their clothes and dishonouring the old and young women, they left the ship and its passengers to their fate. Some of the women, getting an opportunity, threw themselves into sea to save their honour while others committed suicide using knives and daggers.

The Christians were not as skilled in sword fight as the Muslims are….

When report of this incident reached the Emperor and the news-writers of Surat sent to the Court some rupees coined by the English in Bombay with the unholy name of their king struck on them along with some people who had actually suffered, he ordered the capture of the English trade agents

Page 421

Who were posted at the port of Surat. Orders were also issued to I’timad Khan, Mutasaddi of the port of Surat and Sidi Yaqut Khan to make plans for the capture of Bombay. The confusion thus created lasted for several years. The English were not prepared to accept the responsibility of this action, as they knew that Yaqut Khan was disheartened because of having been slighted on a previous occasion they became more active than usual in building bastions and walls and in blocking up roads, so that they made the place quite impregnable. I’timad Khan, the Mutasaddi of the port of Surat, in view of the strength of fortifications of Bombay, thought that the matter was irremediable [1]. In case of the outbreak of hostilities against the people using hats customs duties of the port of Surat would suffer a great loss. He considered himself one of the thrifty officers of the Emperor and did not want to waste a single pice. Although he had arrested some English gumashtas at Surat, secretly he was trying to avert the infamy (of possible defeat) of the English by negotiations. The English [P.424] on hearing about the imprisonment of their gumashtas captured in retaliation every Imperial mansabdar, about whom they heard, on the sea-coast or on water.

Khafi Khan in the fort of Bombay

During the hostilities, the writer of the narrative was acting as an agent of ‘Abd al-Razzaq at Surat. The armed followers of the Mutasaddi of Surat were in full control there. By a strange chance, the writer had an opportunity of meeting the English men from Bombay. I was going to Rahiri with two lakhs [2,00,000] of Rupees in cash and some goods purchased at Surat belonging to ‘Abd al-Razzaq, the fawjdar of Rahiri along with some Imperial stores. I was travelling by sea, and had to pass by the territories of the Portuguese and the English. When I reached near Bombay, and while still in Portuguese territory, I according to the written directions of ‘Abd al-Razzaq, had to wait there for

[1]: i.e. the Capture of Bombay, he thought, was not possible.

Page 422

The guard supplied by Yaqut Khan for ten or twelve days. As there existed an old friendship between the English and ‘Abd al-Razzaq since the days he was at Hayderabad, he had written to the English (commandant) also about the guard. He therefore sent the brother of his Diwan inviting me with sincerity to his presence. The Frankish (Portuguese) captain , and the men in my company, advised me against going there with so much wealth in my charge. The writer of these pages, having however, full trust in God went to the English. I told the brother of his Diwan that during the conversation,if an enquiry was made about the capture of the ship, I would not say things pleasing to them but would give true answers to the questions. The wakil of the English, who was trying his utmost to finish the hostilities, encouraged me and advised me to say every thing boldly and to speak nothing but the truth.

[P. 425] When I entered the fort, I observed that inside the gate from every start on each side of the route well dressed youths of the age of twelve or fourteen stood in rows with excellent muskets on their shoulders. A few steps further, well dressed young men, with beards just appearing and with muskets on their shoulders were seen on both sides. When I advanced a few steps further, I saw English men with long beards and of the same age furnished with similar equipment. After them were seen well dressed musketeers, with shaved beards arranged and drawn in up in ranks. Further on. English men, with white beards, clothed in brocade, and having muskets on their shoulders were seen on either side. Next I saw some handsome aged English men wearing hats with pearls on their borders. In short I saw thus, upto the door of the house in which he lived, nearly seven thousand musketeers drawn in ranks on both sides dressed and accoutred as for review.

I then reached the place where he was sitting on a chair. He preceded me in greetings in his own fashion. He rose from his chair and embraced me and asked me to sit down on a chair in front of him. Under the garb of asking the welfare of ‘Abd al-

Page 423

Razzaq and showing sincerity to him, the discourse turned upon different topics, pleasant and unpleasant, bitter and sweet; questions and answers were made. Of these questions one was about the cause of arrest of his agents. Trusting that God and His Prophet would protect me, I said in answer: “You do not take upon yourself the responsibility of the shameful deeds committed by your men, which are condemned by all sensible men. Your question resembles one raised by a wiseman who despite the rays of the sun all over the world, asks [P.426] where the light was coming from.” He replied: “The people who are hostile to us cast upon us the blame for the fault of others. How have you come to the conclusion that the crime was committed by our men and by what convincing evidence will you prove this?” I replied: “In the ship (Ganj-i-Sawa’i) I had acquaintances, some of whom were wealthy persons, besides two or three darwishes who were free the temptations of this world. I heard from them that at the time of plunder of the ship and of their arrest, there was a party of men, who appeared from their faces and dresses to be English men. They had scars of wounds on their bodies and hands and they said in their own language: ‘These are the scars of the wounds we received at the time of the siege of Sidi Yaqut; but today the blot of those scars have been wiped off our hearts (i.e. we have taken revenge).’ A person who was their fellow traveller and who knew Hindi and Persian, translated their words to my friends.”

On hearing my words, he burst out into laughter and said: “It is perfectly correct. They must have said so, but they are those English men who were wounded and taken prisoner by Yaqut Khan during the siege. Some of them deserted us, became Muslims and took service with that Abyssinian. They stayed with him for some time and fled away. As they could not show their faces to us, they went over to the men of Denkmar [1] also called Sakanas [2] and joined their service. They lay violent hands

[1]: Possibly Denmark

[2]: Possibly Saxon

Page 424

On the ships on the surface of the sea i.e. plunder them and have become their assistants in piracy. The officers of your Emperor are unable to successfully deal with them and therefore put responsibility for piracy upon our men.” I said in reply smilingly: “I have seen today what I had heard about your promptness in reply and your ready wit. All praise to your wisdom. You have given so reasonable and prompt reply in such a case without [P.427] spending a moment in thinking over it. You must however bear in mind that the hereditary rulers of Bijapur and Hayderabad, and Sambha, the accursed, could not escape from the hands of Alamgir [Aurangzeb]. The safety of the island of Bombay is evident!” I then said: “The coining of money in the form of rupees by you is a clear indication of your rebellion.” He replied: “We send every year, to our country, a large amount of money as profit on our mercantile goods. The coins of the Emperor of India are exchanged with loss. Besides this, there is considerable alloy and counterfeiting in Indian coins. Therefore quarrels break up at the time of sale and purchase in the Island. For this reason, I strike my name on the coins within my jurisdiction.”

Besides this, other matters were also discussed, some of which were not liked by him. However, due to his regard for ‘Abd al-Razzaq Khan and his promise to give me security he remained calm, and in accordance with their practice he showed hospitality and invited me to a farewell feast. But as it had been settled between us at the very outset, that no formalities would be observed, I contented myself with accepting ‘atr and pan and was glad to escape from that calamity.

The revenue of the island of Bombay most of which is derived from betel-nuts and cocoa-nuts, does not amount to more than two or three lakhs [2,00,000-3,00,000] of rupees. It is reported that the entire amount of trade of that wicked fellow is not more than twenty lakhs of rupees [20,00,000]. The source of the remaining unstable income of the English is the plunder and capture of the ships going to

The source of the remaining unstable income of the English is the plunder and capture of the ships going to The House of God.

Page 425

The House of God. At intervals of one or two years, they attack these ships, not at the time when loaded with grains. They proceed to Mukhkhah and Jeddah, but when they return bringing gold, silver, Ibrahimis[1] and Riyals they attack the richest one after obtaining secret information.

The Marhatas [P.428] have recently built new fortresses of Khanderi[2] (Kenery), Qulabah, Kansa and Katora opposite the island fortess belonging to the Abyssinians. They collect their war boats around their forts and attack the merchant ships whenever they find an opportunity. In the same way, the Sakanas, also called Bawarils, who are a lawless set of people belonging to Surat, in the Subah of Ahmedabad are notorious pirates. They attack from time to time, small ships coming from Bunder ‘Abbasi and Muscat. But they have not the courage to attack big ships plying on the route to Makkah. The English try to shift their ignomy to the shoulders of Sakanas.

[1]: The coins of Ibrahim Adil Shah

[2]: These are small islands near Janjirah

Why were the British minting silver coins instead of gold ones? As it turns out, the British had access to silver mines in the New World, and they were using cheap New World silver to buy the services of soldiers in India. This would gradually destroy the silver Indian Rupee with inflation (covered in my book). It is amusing to note that Khafi Khan, while being a regular Mughal official, is able to clearly discern the British as different from the other traders who operated in India. He clearly senses their tendency towards economic terrorism and while making note of the high standards of discipline their soldiers possess, also finds their leaders “wicked.” This would be an ominous portent for the upcoming colonizaton of India.

The following is a modern account of the incident, courtesy Wikipedia (abridged),

Every was elected admiral of the new six-ship pirate flotilla despite the fact that Captain Tew had arguably more experience, and now found himself in command of over 440 men while they lay in wait for the Indian fleet [1]. A convoy of twenty-five Mughal ships, including the enormous 1,600-ton Ganj-i-sawai of eighty cannons, and its escort, the 600-ton Fateh Muhammed, were spotted passing the straits of Bab el Mandeb en route to Surat in August 1695. Although the convoy had managed to elude the pirate fleet during the night, the pirates gave chase.

The Dolphin proved to be far too slow, lagging behind the rest of the pirate ships, so it was burned and the crew joined Every on the Fancy. The Amity and Susanna also proved to be poor ships: the Amity fell behind and never again rejoined the pirate squadron (Captain Tew having been killed in a battle with a Mughal ship), while the straggling Susanna eventually rejoined the group. The pirates caught up with the Fateh Muhammed four or five days later.[2] Perhaps intimidated by the Fancy’s forty-six guns or weakened by an earlier battle with Tew, the Fateh Muhammed’s crew put up little resistance; Every’s pirates then sacked the ship, which had belonged to one Abdul Ghaffar, reportedly Surat’s wealthiest merchant. In fact, Ghaffar was so powerful and wealthy, one associate described him as follows: “Abdul Ghafur, a Mahometan that I was acquainted with, drove a trade equal to the English East-India Company, for I have known him to fit out in a year, above twenty sail of ships, between 300 and 800 tons.”[3] While the Fateh Muhammed’s treasure of some £50,000 to £60,000 was enough to buy the Fancy fifty times over,[4] once the treasure was shared out among the pirate fleet Every’s crew received only small shares.[5]

Every now sailed in pursuit of the second Mughal ship, the Ganj-i-sawai (meaning “Exceeding Treasure,” and often Anglicized as Gunsway),[6] overtaking it a few days after the attack on the Fateh Muhammed. With the Amity and Dolphin left behind, only the Fancy, the Pearl, and the Portsmouth Adventure were present for the actual battle.[7]

The Ganj-i-sawai, captained by one Muhammad Ibrahim, was a fearsome opponent, mounting eighty guns and a musket-armed guard of four hundred, as well as six hundred other passengers. But the opening volley evened the odds, as Every’s lucky broadside shot his enemy’s mainmast by the board. With the Ganj-i-sawai unable to escape, the Fancy drew alongside. For a moment, a volley of Indian musket fire prevented the pirates from clambering aboard, but one of the Ganj-i-sawai’s powerful cannons exploded, instantly killing many and demoralizing the Indian crew, who ran below deck or fought to put out the spreading fires. Every’s men took advantage of the confusion, quickly scaling the Ganj-i-sawai’s steep sides. The crew of the Pearl, initially fearful of attacking the Ganj-i-sawai, now took heart and joined Every’s crew on Indian ship’s deck. A ferocious hand-to-hand battle now ensued, lasting two to three hours.[8] In any case, after several hours of stubborn but leaderless resistance, the ship surrendered. In his defense, Captain Ibrahim would later report that “many of the enemy were sent to hell.”[9] Indeed, Every’s outnumbered crew may have suffered anywhere from several to over a hundred casualties, granting these figures are uncertain.[10].

Although stories of brutality by the pirates have been dismissed by sympathizers as sensationalism, they are corroborated by the depositions Every’s men provided following their capture. John Sparkes testified in his “Last Dying Words and Confession” that the “inhuman treatment and merciless tortures inflicted on the poor Indians and their women still affected his soul,” and that, while apparently unremorseful for his acts of piracy, which were of “lesser concern,” he was nevertheless repentant for the “horrid barbarities he had committed, though only on the bodies of the heathen.”[11] Philip Middleton testified that several of the Indian men were murdered, while they also “put several to the torture” and Every’s men “lay with the women aboard, and there were several that, from their jewels and habits, seemed to be of better quality than the rest.”[12] Furthermore, on 12 October 1695, Sir John Gayer, then-governor of Bombay and president of the East India Company, sent a letter to the Lords of Trade, writing: “It is certain the Pyrates, which these People affirm were all English, did do very barbarously by the People of the Gunsway and Abdul Gofor’s Ship, to make them confess where their Money was, and there happened to be a great Umbraws Wife (as Wee hear) related to the King, returning from her Pilgrimage to Mecha, in her old age. She they abused very much, and forced severall other Women, which Caused one person of Quality, his Wife and Nurse, to kill themselves to prevent the Husbands seing them (and their being) ravished.[13]”

Later accounts would tell of how Every himself had found “something more pleasing than jewels” aboard, usually reported to be Emperor Aurangzeb’s daughter or granddaughter. (According to contemporary East India Company sources, the Ganj-i-sawai was carrying a “relative” of the Emperor, though there is no evidence to suggest that it was his daughter and her retinue.[14]) At any rate, the survivors were left aboard their emptied ships, which the pirates set free to continue on their voyage back to India. The loot from the Ganj-i-sawai, the greatest ship in the Muslim fleet, totaled somewhere between £200,000 and £600,000, including 500,000 gold and silver pieces. All told, it may have been the richest ship ever taken by pirates (see Career wealth below). All these things combined made Every the richest pirate in the world. The value of the Ganj-i-sawai’s cargo is not known with certainty. Contemporary estimates differed by as much as £300,000, with £325,000 and £600,000 being the traditionally cited numbers. The latter estimate was the value provided by the Mughal authorities, while the East India Company estimated the loss at approximately £325,000, nevertheless filing a £600,000 insurance claim.[15] If the larger estimate of £600,000 is taken, this would be equivalent to $400 million.

If the larger estimate of £600,000 is taken, the value of the Mughal ship’s cargo would be equivalent to $400 million today!

Notes:

[1]: Joel H. Baer. Pirates of the British Isles (London: Tempus Publishing, 2005) 99.

[2]: E. T. Fox. King of the Pirates: The Swashbuckling Life of Henry Every (London: Tempus Publishing, 2008) 73-79.

[3]: Jan Rogoziński. Honor Among Thieves: Captain Kidd, Henry Every, and the Pirate Democracy in the Indian Ocean (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000) 248.

[4]: Colin Woodard. The Republic of Pirates: Being the True and Surprising Story of the Caribbean Pirates and the Man Who Brought Them Down (Orlando, FL: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007) 21.

[5]: Douglas R. Burgess. The Pirates’ Pact: The Secret Alliances Between History’s Most Notorious Buccaneers and Colonial America (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2009) 136.

[6]: Tim Travers. Pirates: A History (London: Tempus Publishing, 2007) 41.

[7]: Jan Rogoziński. Honor Among Thieves: Captain Kidd, Henry Every, and the Pirate Democracy in the Indian Ocean (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000) 85.

[8]: Peter Earle. The Pirate Wars (NY: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2006) 117.

[9]: Joel H. Baer. Pirates of the British Isles (London: Tempus Publishing, 2005) 102.

[10]: E. T. Fox. King of the Pirates: The Swashbuckling Life of Henry Every (London: Tempus Publishing, 2008) 60, 79.

[11]: Charles Grey. Pirates of the Eastern Seas (1618–1723): A Lurid Page of History (London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co. 1933) 151.

[12]: Charles Grey. Pirates of the Eastern Seas (1618–1723): A Lurid Page of History (London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co. 1933) 151.

[13]: John Franklin Jameson.”Case of Henry Every,” Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period: Illustrative Documents (New York, NY: Macmillan Publishers, 1923) doc. no. 60; pp. 153–188. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

[14]: E. T. Fox. King of the Pirates: The Swashbuckling Life of Henry Every (London: Tempus Publishing, 2008) 80-81.

[15]: Douglas R. Burgess. The Pirates’ Pact: The Secret Alliances Between History’s Most Notorious Buccaneers and Colonial America (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2009) 138.

The Aftermath

Aurangzeb immediately ordered the closure of all East India Company factories in India (four were immediately closed). British subjects and officials were immediately arrested. He also ordered an armed attack on Bombay Castle again, with the aim of expelling the British from India once and for all [1]. The East India Company once again rushed to placate Aurangzeb, agreeing to pay all financial damages related to the incident. A bounty was put on Every’s head, and in British parliament, he was declared an enemy of the human race. A proclamation was issued by the Privy Council of Scotland on 18 August 1696 offering reward for his apprehension. The first ever international manhunt in Western history was launched by the British to apprehend him.

While Khafi Khan may have never known it, his personal intervention may have alarmed the British into distancing themselves as much as they could from Every. Khafi Khan had insider information that this act of piracy was directly connected to the Bombay Castle. And he did not hesitate to let the British commander of the Castle know that he would let his Mughal superiors know the same.

Sadly, Aurangzeb and the later Mughals could never dedicate themselves to extirpating the British from India after this incident. The Marathas were causing far more destruction to North Indian cities, and protecting these cities became the primary objective of Mughal military commanders. The Mughal Empire soon imploded due to an internal conspiracy attributed to shadowy groups that appear to be a wing of the Illuminati operating in the Islamic World for centuries. By the time the Mughals had recovered, the British had already dug their grave.

Notes:

[1]. John Keay. The Honourable Company: A History of the English East India Company (London: HarperCollins, 1991) 187.

The Coverup

There are strong indications that organized piracy conducted by Western ships was the work of Illuminati families. They seemed to avoid targeting ships of the Illuminati owned East India Companies. The skull and crossed bones which became their most well-known insignia is an occult symbol, with the crossed bones similar to a rotated cross, representing the four directions taken by the Tribes of Israel. Later, this symbol would resurface as the symbol of the elite Yale Skull and Bones fraternity, which includes several American Presidents among its initiates. A similar symbol was seen worn by members of the Nazi SS paramilitary units. Christian Church figures and religious authorities never condemned the activities of European pirates.

Establishment historians have tried their best to portray Henry Every as a commoner, even though he may be linked to the Every baronets of Britain. The surname Avery often occurs in elitist circles and may be derived from Every. Interestingly, Henry Every started using the alias of Benjamin Bridgeman when he started piracy.

According to a ballad purportedly written by Henry Every himself sometime between May and July 1694 (one year before the incident), his pirate flag had four golden chevrons against a red background. According to a British Baronetcy history website,

Every, of Egginton.— Simon Every, who was created a baronet in 1641, was of a Somersetshire family: he settled at Egginton in this county in consequence of his marriage with Mary, elder daughter and coheir of Sir Henry Leigh. Sir Henry, the third baronet, married one of the coheiresses of Russel, of Strensham in Worcestershire, but left no issue either by her or by his second wife. His brother, Sir John Every the succeeding baronet, was a naval officer of some note in the reign of King William. Upon the death of his younger brother the Reverend Sir John Every, the seventh baronet, in 1779, the elder branch became extinct, and the title devolved to Mr. Edward Every, then of Derby, being the fourth in descent from Francis, third son of Sir Simon, the first baronet, which Francis was buried at Egginton in 1708; his son, Sir Henry, is the present baronet.

Arms:—Or, four chevronels, Gules.

Crest:—An unicorn’s head, couped, Proper.

Curzon, of Kedleston. See Lord Scarsdale.

As one can see, four Chevrons can be found in an official coat of arms of the Every baronets.

Another anonymous ballad runs like this,

For thirteen days aboard the Ganj, we made a merry sport

A thousand pounds of Mughal gold, and whisky, rum and port

Some men we shot and some we walked and some of them did hang

And while we made free with the girls, well this is what we sang:Thirteen is a number associated with the Illuminati (There are thirteen families).

Every’s early years remain a mystery. There are indications that Every’s father was a trading captain who had served in the Royal Navy under Admiral Robert Blake, who is considered to be one of the most important British admirals of the 17th century. He is also considered one of the founders of British naval supremacy. Every did serve the Royal Navy in several important battles. After that, he was picking up slaves off the Guinea coast, and sometimes even tricking slave traders into being captured for slavery. When he began his pirate career, Every wrote a letter addressed to British ship commanders, asking them to make a particular flag-signal so that he could identify them as British. He guaranteed not to attack them. This affinity towards the East India Company, whose ships were carrying large amounts of wealth, is indeed strange.

It is still unclear how Every persuaded the rest of the pirate ships to leave the Mughal loot in his care while he quietly slipped out into the night on board the Fancy. The Fancy resurfaced in Bahamas. Despite the proclamation for the immediate arrest of Every, the British governor of Bahamas gave sanctuary to him, and later helped him destroy the Fancy by violently driving it against rocks. This was done in a futile attempt to cover-up Every’s presence in the British territory of Bahamas. When orders for Every’s arrest arrived in the Bahamas, he vanished.

There are indications that Every and twenty of his men returned to Britain around 1696 [1], and that he settled in Devon, dying in 1714 [2]. Some of these men were rounded up and executed, possibly to cover the link to Every. One of them, John Dann, recieved an official pardon and became a goldsmith-banker (Coggs & Dann), presumably with the loot. Every, and his loot were effectively hidden from history. What Every did to the Ganj-i-sawai would be repeated by the British Empire on a gargantuan scale. But this time victim was not a ship but the entire Indo-Islamic civilization.

Notes:

[1]: Jan Rogoziński. Honor Among Thieves: Captain Kidd, Henry Every, and the Pirate Democracy in the Indian Ocean (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000) 90.

[2]: George Francis Dow & John Henry Edmonds. The Pirates of the New England Coast 1630–1730. (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1923) 348.