History of Art, The Power Ballads: Don’t Catch You Slippin’ Up!

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Big Tech’s Effort to Silence Truth-tellers: Global Research Online Referral Campaign

***

Of all art forms the ballad has the benefit of expediency. From event, to composition, to broadcast: no art form can compete with the efficacy and proliferation of a good song. The reach and emotional impact of a ballad, “a form of verse, often a narrative set to music” allows for any event affecting individuals or groups to rapidly become popularised and understood globally. While historically ballads tended to be sentimental, their descendant, the protest song, sits alongside modern ballads with ease.

While both the ballad and the protest song can have as their basis socio/political narratives, their differences are more in the formal qualities of tempo. Ballads still tend to be slower than protest songs, but conveying in emotion what they lose in excitement.

While the ballad may satisfy with its unhurried melody and storytelling, the protest song has an immediacy of lyric and beat that gives vocal power to mass events like concerts and demonstrations.

History of the Ballad

Ballads have a long history in European culture. They started out as the “medieval French chanson balladée or ballade, which were originally ‘dance songs’. Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and song of Britain and Ireland from the Late Middle Ages until the 19th century. They were widely used across Europe, and later in Australia, North Africa, North America and South America.” In the nineteenth century they were associated with sentimentality which led to the word ballad “being used for slow love songs from the 1950s onwards.”

In Ireland ballads have been a very important part of the nationalist struggle against British colonialism since the seventeenth century. They reached the zenith of their popularity in the 1960s with the Dubliners, and the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem. Ballad folk groups are still in demand today in Europe and the USA.

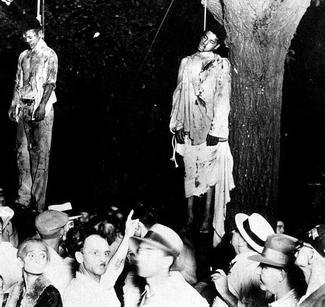

Ballads tend to have a slower tempo that allows the audience to experience the nuances of the lyrics. An early and powerful example of this is ‘Strange Fruit’, a song written and composed by Abel Meeropol (under his pseudonym Lewis Allan) and recorded by Billie Holiday in 1939. A ballad and a protest song, ‘Strange Fruit’ “protests the lynching of Black Americans with lyrics that compare the victims to the fruit of trees. Such lynchings had reached a peak in the Southern United States at the turn of the 20th century and the great majority of victims were black.” ‘Strange Fruit’ has been described as a call for freedom and is seen as an important initiator of the civil rights movement. The lyrics are full of horror and bitter irony:

“Southern trees

Bearing strange fruit

Blood on the leaves

And blood at the roots

Black bodies

Swinging in the Southern breeze

Strange fruit hangin’

From the poplar trees

Pastoral scene

Of the gallant south”

Woodie Guthrie, ‘Dust Bowl Ballads’ (1940)

Woodrow Wilson Guthrie (1912–1967) was an American singer-songwriter and composer who was one of the most important figures in American folk music. His songs focused on themes of American socialism and anti-fascism. As a young man he migrated to California to look for work and his experiences of the conditions faced by working class people. This led him to produce Dust Bowl Ballads, an album of songs grouped around the theme of the Dust Bowl storms that destroyed crops and intensified the economic impact of the Great Depression in the 1930s. ‘Dust Bowl Ballads’ is thought to be one of the earliest concept albums.

The songs lyrics tell of the storms and their apocalyptic effect on the local farmers:

“On the 14th day of April of 1935

There struck the worst of dust storms that ever filled the sky

You could see that dust storm comin’, the cloud looked deathlike black

And through our mighty nation, it left a dreadful track

From Oklahoma City to the Arizona line

Dakota and Nebraska to the lazy Rio Grande

It fell across our city like a curtain of black rolled down

We thought it was our judgement, we thought it was our doom

[…]

The storm took place at sundown, it lasted through the night

When we looked out next morning, we saw a terrible sight

We saw outside our window where wheat fields they had grown

Was now a rippling ocean of dust the wind had blown”

Pete Seeger, ‘We Shall Overcome’ (1967)

Peter Seeger (1919–2014) was a popular American folk singer who was regularly heard on the radio in the 1940s, and in the early 1950s had a string of hit records as a member of The Weavers, some of whom were blacklisted during the McCarthy Era. In the 1960s, Seeger became “a prominent singer of protest music in support of international disarmament, civil rights, counterculture, workers’ rights, and environmental causes.”

‘We Shall Overcome’ is believed to have originated as a gospel song known as ‘I’ll Overcome Some Day’. In 1959, the song began to be associated with the civil rights movement as a protest song, with Seeger’s version focusing on nonviolent civil rights activism. It became popular all over the world in many types of protest activities.

The song is a very understated (both musically and lyrically) declaration of protest and unity in the face of oppression:

“We shall overcome

We shall overcome

We shall overcome some day

Oh, deep in my heart

I do believe

We shall overcome some day”

Special A.K.A., ‘Free Nelson Mandela’ (1984)

In contrast, the lively anti-apartheid song ‘Free Nelson Mandela’ written by British musician Jerry Dammers, and performed by the band the Special A.K.A. was a hugely popular song in 1984 that led to the global awareness of the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela by the apartheid South African government:

“Free Nelson Mandela

Twenty-one years in captivity

Shoes too small to fit his feet

His body abused but his mind is still free

Are you so blind that you cannot see?

I said free Nelson Mandela”

Rage Against The Machine, ‘Sleep Now in the Fire’ (1999)

Rage Against the Machine was an American rock band from Los Angeles, California. Formed in 1991, “the group consisted of vocalist Zack de la Rocha, bassist and backing vocalist Tim Commerford, guitarist Tom Morello, and drummer Brad Wilk.”

The video for ‘Sleep Now in the Fire’ turned a protest song into an actual protest when the band played on Wall Street in front of the New York Stock Exchange:

“The music video for the song, which was directed by Michael Moore with cinematography by Welles Hackett, features the band playing in front of the New York Stock Exchange, intercut with scenes from a satire of the popular television game show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? which is named Who Wants To Be Filthy Fucking Rich. […] The video starts by saying that on January 24, 2000, the NYSE announced record profits and layoffs, and on the next day New York mayor Rudy Giuliani decreed that Rage Against the Machine “shall not play on Wall Street”. The shoot for the music video on January 26, 2000 caused the doors of the New York Stock Exchange to be closed.”

The lyrics are spartan, yet cover many topics: bible-belt conservatism, the corrupting aspects of wealth and its connection with right-wing politics. The second verse gives a potted history of the USA: ‘I am the Nina, the Pinta, the Santa Maria’ (Columbus’ three ships), ‘The noose and the rapist, the fields overseer’ (the slave system), The agents of orange (the Vietnam war), The priests of Hiroshima’ (Oppenheimer’s fascination with mysticism). Any shorter and these lines could almost be described as a haiku embedded within the song. The third verse deals with the future: ‘For it’s the end of history, It’s caged and frozen still, There is no other pill to take, So swallow the one That makes you ill’ referencing Francis Fukuyama’s argument “that the worldwide spread of liberal democracies and free-market capitalism of the West and its lifestyle may signal the end point of humanity’s sociocultural evolution and political struggle, and become the final form of human government”, ‘caged’ because there is no alternative, and will continue this way (of making us ‘ill’) with no viable socio/political alternative vision:

“The world is my expense

The cost of my desire

Jesus blessed me with its future

And I protect it with fire

So raise your fists and march around

Dont dare take what you need

I’ll jail and bury those committed

And smother the rest in greed

Crawl with me into tomorrow

Or i’ll drag you to your grave

I’m deep inside your children

They’ll betray you in my name

Hey!

Hey!

Sleep now in the fire

The lie is my expense

The scope with my desire

The party blessed me with its future

And i protect it with fire

I am the Nina, the Pinta, the Santa Maria

The noose and the rapist, the fields overseer

The agents of orange

The priests of Hiroshima

The cost of my desire

Sleep now in the fire

For it’s the end of history

It’s caged and frozen still

There is no other pill to take

So swallow the one

That makes you ill

The Nina, the Pinta, the Santa Maria

The noose and the rapist, the fields’ overseer

The agents of orange

The priests of Hiroshima

The cost of my desire

Sleep now in the fire.”

Bill Callahan, ‘America!’ (2011)

In Bill Callahan’s (born 1966) song and video ‘America!’ he contrasts the symbols and perception of America globally with its darker past. He mentions legendary American songwriters and performers Mickey Newbury, Kris Kristofferson, George Jones and Johnny Cash and their past roles in the army, showing the deep connection between culture and the military in the USA. Callahan lists countries where the USA has been: Afghanistan, Vietnam, Iran, and ends with Native America, turning its colonialism and imperialism back on itself. There is also an oblique reference to the system of haves and have-nots (‘Others lucky suckle teat’) ending with the slight change ‘Ain’t enough to eat’ emphasizing the growing poverty in the richest country on earth:

“America!

You are so grand and golden

Oh I wish I was deep in America tonight

America!

America!

I watch David Letterman in Australia

America!

You are so grand and golden

I wish I was on the next flight

To America!

Captain Kristofferson!

Buck Sergeant Newbury!

Leatherneck Jones!

Sergeant Cash!

What an Army!

What an Air Force!

What a Marines!

America!

[Afghanistan, Vietnam, Iran, Native America]

Well, everyone’s allowed a past

They don’t care to mention

Well, it’s hard to rouse a hog in Delta

And it can get tense around the Bible Belt

Others lucky suckle teat

Others lucky suckle teat

America!”

Childish Gambino, ‘This Is America’ (2018)

In his video, ‘This Is America’, Childish Gambino (Donald Glover, born 1983) shocked his viewers, who were not used to seeing the cinematic realism of gun violence in a music video. Gambino focuses more on the present than the past, while using cars from the 1990s probably as a symbol of poverty. The violence and drugs scene behind pleasure-seeking party-goers is emphasised with an execution at the start and followed up by a mass murder of a gospel choir. His demeanor constantly changes very suddenly, from dancing one moment, to exhorting his clients another, then cold-blooded killing, yet despite it all, running for his life in the end as his life style catches up with him:

“We just wanna party

Party just for you

We just want the money

Money just for you

I know you wanna party

Party just for me

Girl, you got me dancin’ (yeah, girl, you got me dancin’)

Dance and shake the frame

We just wanna party (yeah)

Party just for you (yeah)

We just want the money (yeah)

Money just for you (you)

I know you wanna party (yeah)

Party just for me (yeah)

Girl, you got me dancin’ (yeah, girl, you got me dancin’)

Dance and shake the frame (you)

This is America

Don’t catch you slippin’ up

Don’t catch you slippin’ up

Look what I’m whippin’ up

This is America (woo)

Don’t catch you slippin’ up

Don’t catch you slippin’ up

Look what I’m whippin’ up”

Bob Dylan, ‘Murder Most Foul’ (2020)

In 2020, Bob Dylan (born 1941) released this seventeen-minute track, “Murder Most Foul”, on his YouTube channel, based on the assassination of President Kennedy. It is a long, slow ballad that intertwines culture and politics, contrasting the optimism of the one with the stark brutality of the other. It is the poetry of America re-examing its past at its best, the detail and condemnation in its lyrics reflecting a political undercurrent that refuses to accept modern myths, a murder ‘most foul’:

“It was a dark day in Dallas, November ’63

A day that will live on in infamy

President Kennedy was a-ridin’ high

Good day to be livin’ and a good day to die

Being led to the slaughter like a sacrificial lamb

He said, “Wait a minute, boys, you know who I am?”

“Of course we do, we know who you are!”

Then they blew off his head while he was still in the car

Shot down like a dog in broad daylight

Was a matter of timing and the timing was right

You got unpaid debts, we’ve come to collect

We’re gonna kill you with hatred, without any respect

We’ll mock you and shock you and we’ll put it in your face

We’ve already got someone here to take your place

The day they blew out the brains of the king

Thousands were watching, no one saw a thing

It happened so quickly, so quick, by surprise

Right there in front of everyone’s eyes

Greatest magic trick ever under the sun

Perfectly executed, skillfully done

Wolfman, oh Wolfman, oh Wolfman, howl

Rub-a-dub-dub, it’s a murder most foul

[…]

Don’t worry, Mr. President, help’s on the way

Your brothers are comin’, there’ll be hell to pay

Brothers? What brothers? What’s this about hell?

Tell them, “We’re waiting, keep coming,” we’ll get them as well

Love Field is where his plane touched down

But it never did get back up off the ground

Was a hard act to follow, second to none

They killed him on the altar of the rising sun

Play “Misty” for me and “That Old Devil Moon”

Play “Anything Goes” and “Memphis in June”

Play “Lonely at the Top” and “Lonely Are the Brave”

Play it for Houdini spinning around in his grave

Play Jelly Roll Morton, play “Lucille”

Play “Deep in a Dream”, and play “Driving Wheel”

Play “Moonlight Sonata” in F-sharp

And “A Key to the Highway” for the king of the harp

Play “Marching Through Georgia” and “Dumbarton’s Drums”

Play darkness and death will come when it comes

Play “Love Me or Leave Me” by the great Bud Powell

Play “The Blood-Stained Banner”, play “Murder Most Foul””

Hope for the Future…

These songs show us that, despite the music industry’s continuing avalanche of industrial pop, composers and bands are still able to produce music that as an art form can combine melody and criticism, that can look behind facades and describe the reality they see – which we hear only as background noise. It shows the way to other art forms that take so much time and energy and money to get up and running, that a fight for more radical content is possible and necessary.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed country by country here. Caoimhghin has just published his new book – Against Romanticism: From Enlightenment to Enfrightenment and the Culture of Slavery, which looks at philosophy, politics and the history of 10 different art forms arguing that Romanticism is dominating modern culture to the detriment of Enlightenment ideals. It is available on Amazon (amazon.co.uk) and the info page is here.

He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

Featured image: Abel Meeropol cited this photograph of the lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, August 7, 1930, as inspiring his poem. Meeropol published the poem under the title “Bitter Fruit” in January 1937 in The New York Teacher, a union magazine of the New York teachers union. Though Meeropol had asked others (notably Earl Robinson) to set his poems to music, he set “Strange Fruit” to music himself.