History: How Britain Protected Ukraine’s Waffen-SS Galitsia Division in the Wake of World War II

Amid the continued support given to the fascist politicians and military of Ukraine by western governments, many people are asking how such a betrayal of the sacrifices of the Allies in World War Two could take place. However, what most people are unaware of, in large part due to an ever-more corrupted media, is that these governments have a shocking history of protecting the perpetrators of some of the most terrible crimes of that war. One of the most egregious examples of this practice of shielding war-criminals from justice was confirmed in 2005 with the declassification of British Home Office papers showing that the British government protected at least 8,000 members of the Waffen-SS Galitsia Division from the justice that awaited them in the Soviet Union.

When Nazi Germany surrendered to the Allied Powers in May 1945, the 14th Waffen-SS ‘Galitsia’ Division, made up of Ukrainian volunteers, continued to retreat westward from their positions in Austria in order to avoid capture and punishment by the advancing Red Army. The Division—approximately 10,000 soldiers—ultimately chose to surrender to British and American forces and was briefly sent to an internment camp in Spittal an der Drau, Austria. The British government, in contravention of the agreements made at the Yalta Conference, refused to repatriate the Galitsia Division to the Soviet Union, instead transferring them to another internment camp in Bellaria-Igea Marina, in northern Italy. It was here that a troika of prominent Ukrainian fascists—Mykola Lebed, Father Ivan Hry’okh and Bishop Ivan Buchko—persuaded the Vatican to intercede on behalf of the soldiers, whom Bishop Buchko described as “good Catholics and fervent anti-communists.”

Galitsia Division troops interned at Rimini, Italy

As a result of this intercession, the British and American authorities overseeing the internment camp remained steadfast in their refusal to abide by their obligation to repatriate the soldiers to the Soviet Union. One of the principal British proponents of the decision not to repatriate the Galitsia Division was Major Denis Hills. Major Hills was keen on protecting these soldiers, and despite admitting that he “knew about the SS”, he said the army “was not interested in war crimes.”

According to British academic, Stephen Dorril, in his book M16: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Service, Major Hills was a self-described fascist and a staunch anti-communist who took it upon himself to ensure that the Galitsia Division would be transferred to Britain. Hills personally advised the head of the Division, Major Yaskevycz, to instruct his men that when questioned by the Soviet repatriation commission they must lie and insist that they were forced to serve alongside the Nazis and were not by any means volunteers. As a result of this, and due to British fears that improved relations between Italy and the Soviet Union could result in repatriation, the decision was made on April 1st, 1947, to relocate at least 8,000 members of the Galitsia Division to Britain.

Troops of Galitsia Division being transported to Britain

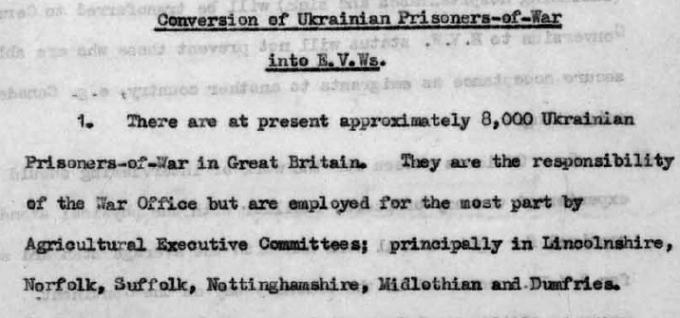

Documents from the British Home Office that were declassified in 2005 reveal in great detail the lengths to which government officials went to grant citizenship and employment to the members of the Galitsia Division. This was a process that was greatly encouraged by politicians of Ukrainian origin like Gordon Bohdan Panchuk, a Canadian MP who put significant pressure on the British Home Office to extend “kind and sympathetic understanding and favourable action” towards the Division. Panchuk further threatened Home Office officials that any discussions of repatriation or ill-treatment of the soldiers would result in a negative political reaction from the Ukrainian communities of Canada and Britain.

The Home Office documents also show a general awareness of the background of the men of the Galitsia Division. It was well known that the war record of these soldiers was “bad and difficulties are likely to arise if they are employed with Poles.” Despite this, the tendency within these correspondences was to overlook the recent history of the Galitsia Division and its role within the Waffen-SS. There were, however, notable objections from Home Office employees assigned to this matter, including that of Beryl Hughes, who found it:

difficult to understand the Ministry of Labour attitude over these POWs. To strain at the gnat of the PLF while appearing to be prepared to face with equanimity the prospect of swallowing a large-sized camel in the shape of upwards of 4,000 undisputed volunteers of the Wehrmacht seems to me the height of absurdity…I cannot help having serious misgivings about their attempt to foist the Ukrainian POWs on the labour market as just another batch of EVWs. [European Volunteer Workers].

Another Home Office official by the name of F.L.F Devey referred to the ‘Surrendered Enemy Personnel’ (SEP) status given to the Galitsia Division as a “pleasant fiction” that was originally enabled during their internment in Italy and overshadowed their true status as prisoners of war.

An interesting component to these documents, and particularly to the solicitations of the Canadian MP Panchuk, was the appeal to sympathy for the men of the Galitsia Division due to their fighting against Russians and communists rather than against “the western allies”. This logic would also be utilized by the CIA in later years, with high ranking operatives such as Harry Rositzke explaining that leading up to, and during, the Cold War anyone could be considered an ally “as long as he was anti-communist…you didn’t look at their credentials too closely.”

Even if there was an inclination to take a closer look at the credentials of the soldiers who made up the Galitsia Division, the British government had taken steps to obscure the dark history of these men. Dr. Stephen Ankier, a pharmacologist turned Holocaust researcher, brought to light the importance of the ‘Rimini list’. This was a classified document that disallowed the ability to track the members of the Division that were transferred to Britain and furthermore blocked efforts to “do anything about them, despite the suspicion that there were war criminals among that group, who were living in Britain.” One of the advantages of the Rimini list was that the British government would be able to better hide the identities of those former SS-Galitsia Division soldiers who would eventually join M16 and the British military in order to aid the anti-Soviet campaign.

An inquiry conducted by the former British MP, Rupert Allason, found that a significant number of the Division was taken to RNAS [Royal Naval Air Station ‒ed.] Crail in Scotland in order to aid with the teaching of the Russian language to British intelligence recruits. Furthermore Allason told the British parliament in 1990 that he had:

obtained evidence from people who served there [RNAS Crail] and were taught Russian by people who openly boasted about the atrocities they had committed…Those boasts were known to British national service men going into the Intelligence Corps and they must have been known to the British government in subsequent years.

Despite this evidence, that by many accounts was available to the British government for decades, no meaningful action was taken and there has been no official recognition of the British role in shielding thousands of war-criminals from justice. Even more shocking than this is the fact that the acceptance of WWII-era war criminals into Britain was not limited to these 8,000 Ukrainian fascists, but also allowed for the protection of a significant number of Axis soldiers. British historians Andrew Thompson and David Cesarani have in their research shown that “war criminals of a range of nationalities did enter Britain” through avenues such as post-war workers’ programs and resettlement initiatives that sought to prevent repatriation to Soviet territories.

In light of this information the logic of contemporary western support for fascism in Ukraine becomes clearer, especially in the context of the contemporary Russophobic hysteria which relies so heavily on post-WWII anti-Soviet rhetoric. Images of British and American politicians embracing the defenders of Ukraine’s fascist past were shocking at first, but now can be seen as the continuation of a decades-long political tradition that betrays the true heroes and victims of the Second World War.