History: How Britain Assisted the Soviet Union’s Fight Against Hitler

In previous installments of the Episodes, we have frequently described the obvious examples of British diplomatic maneuvering in regard to Hitler immediately prior to and at the beginning of World War II (please read, for example, the chapters Poland Betrayed and Who Signed the Death Sentence for France in 1940?) The main goal of Britain’s policy at that time was to set German fascism on a collision course with the USSR. The non-aggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union that was signed in August 1939 upset the Foreign Office’s plans in many respects, but in no way changed Great Britain’s strategic stance.

After France’s crushing, almost instantaneous defeat, Hitler, now operating from a position of strength, resumed his attempts to reach an agreement with Great Britain on the division of global spheres of influence – efforts that had been suspended in the summer of 1939. We have already written about his famous “peace-loving” speech in the Reichstag on July 19, 1940. The radio address – “We Remain Unmoved By Threats” – that was broadcast in response by the current head of the Foreign Office, Lord Halifax, was unapologetically defiant:

The peoples of the British Commonwealth, along with all those who love the trust and justice and freedom will never accept this new world of Hitler’s.

But upon close examination of the details of the odd war that followed, known as the “Battle of Britain,” one is struck by a sense of the grotesqueness of what actually occurred. During much of that campaign, German aces attacked their enemy’s military installations. The British alternated their air raids on military targets with their bombardment of German cities. For example, in late August 1940, British bombers strafed Berlin. But not until Sept. 7 did German aircraft launch regular raids over London. By the time the Battle of Britain was over, 842 Londoners had died during the German Blitz and the famous attack on Coventry on Nov. 14, 1940 left 568 victims. Germany’s share of civilian casualties from British air raids was incomparably higher (although surprisingly there are still no official statistics on the number of these deaths). We are constantly faced with one inescapable fact: Hitler is waging only a half-hearted war on Britain, merely reciprocating with counter attacks. Obviously that is not how you win a war. But if we start with the assumption that the Führer did not actually intend to win a war against Britain, but was only seeking to make London more amenable to peace terms that were more favorable to Germany, then the logic behind the events becomes clear. Great Britain did not need peace, she needed Hitler to turn eastward!

Rudolf Hess in Spandau prison, 1987

Throughout this period, the leader of the Reich engaged in unrelenting yet generally unsuccessful attempts to negotiate with London through unofficial channels. Without question the most pivotal and mysterious figure in these attempts was Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess, the only Nazi war criminal sentenced to life imprisonment who never managed to get out of prison alive. Without delving into the details (worthy of a detective novel) of his whirlwind of activity between the fall of 1940 and the spring of 1941 (suffice it to mention the story of his famous Sept. 23, 1940 letter to the Duke of Hamilton, which was later “lost”), it must be admitted that the quintessence of these attempts was Hess’s flight to Britain on May 10, 1941 with the intent of obtaining a promise from Britain that she would not enter the fray in support of the USSR should Operation Barbarossa be launched.

In May 1941, London gave Hitler the assurances he so desired of her neutrality in his future war with the USSR and of the establishment of the peace Germany had so long awaited once Russia was soundly defeated … Otherwise, Hitler would never have decided to attack the USSR. This is the biggest secret of Britain’s WWII policy, and in order to keep it hushed up, Nazi #3 Rudolf Hess spent 46 years in prison and was strangled at the age of 93 with an electrical cord.

It was to be expected that the new documents on the Hess case that were declassified by the Foreign Office several months ago would not shed any light on this critically important angle of his negotiations in London in May 1941.

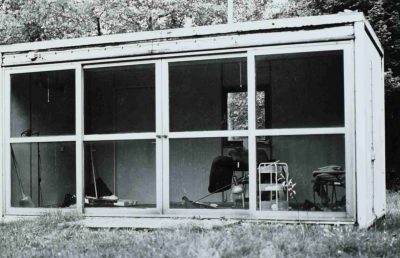

The summer house in Spandau prison garden where Rudolf Hess was killed on Aug 17, 1987

And thus by June 1941, the situation in the European theater of war was back on a track that was favorable to Britain. London’s first order of business was to drag the war out as long as possible in the East – a quick victory by either side would have posed unacceptable risks to British interests in Europe and the Middle East. Therefore, British aid to Russia needed to be offered in dribs and drabs. Great Britain had verbally joined sides with the USSR immediately after June 22, 1941, but in terms of real action – London not only did not begin providing assistance, it did not even make any moves toward binding itself through explicit, formal commitments. On July 12, 1941 an agreement to render mutual military assistance was signed in Moscow. This document had only two clauses:

1. The two Governments mutually undertake to render each other assistance and support of all kinds in the present war against Hitlerite Germany.

2. They further undertake that during this war they will neither negotiate nor conclude an armistice or treaty of peace except by mutual agreement.

It would be hard not to notice that this document does not cite anything specifically and is extremely vague, which had the net result that Britain did not immediately do anything at all in that joint struggle against the Nazis or in its efforts to offer at least some help to the Soviet Union.

After a few weeks, Ivan Maisky, the Soviet ambassador in London, indignantly berated the head of the British Foreign Ministry:

The USSR and England are allies in this terrible war, but how is our British ally helping us at present? It is doing nothing at all! All these last ten weeks we have been fighting alone! … We have asked you to open up a second front, but you have refused. At the Atlantic Conference you promised us wide-ranging economic and military assistance, but so far that has been nothing but fine words … Only think, our air service has asked yours to immediately provide 60 large bombs – and what then? … A lengthy correspondence ensued, as a result of which we were promised six bombs! (Ivan Maisky, Memoirs of a Soviet Ambassador)

Amb. Ivan Maisky with his spouse arriving to London, 1932

The British were well pleased all around: a war was being fought, but they were doing little of the fighting. Hitler had turned his attentions eastward and the raids over the British Isles came to an end. A few more months passed, and on Nov. 8, 1941, Stalin himself, in a letter to Churchill, demanded an explicit, clear treaty, because without such, Downing Street was able to send only empty words of support instead of actual military assistance.

“I agree with you,” Stalin wrote, “that we need clarity, which at the moment is lacking in relations between the U.S.S.R. and Great Britain. The unclarity is due to two circumstances: first, there is no definite understanding between our two countries concerning war aims and plans for the post-war organisation of peace; secondly, there is no treaty between the U.S.S.R. and Great Britain on mutual military aid in Europe against Hitler. Until understanding is reached on these two main points, not only will there be no clarity in Anglo-Soviet relations, but, if we are to speak frankly, there will be no mutual trust …”

After Stalin’s insistence and Churchill’s prolonged attempts to refuse, the USSR and Britain became allies in the true sense of the word only in May 1942, when a full-fledged treaty of alliance was signed during Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov’s visit to London. But this fact did not change the bottom line of London’s policy at all. One month after signing the treaty of alliance, the British quite blatantly betrayed the Soviet Union. One of the most dramatic and puzzling pages out of the history of World War II was the German decimation of the PQ 17 ship convoy.

Signing of the Soviet-British Treaty, London, May 26, 1942

To be continued…

The presented text was taken from the book by the Russian historian, writer and political activist Nikolay Starikov “Proxy Wars“, St.Petersburg, 2017. Adapted and translated by ORIENTAL REVIEW.

Previous Episodes

Episode 17. Britain – Adolf Hitler’s star-crossed love

Episode 16. Who signed death sentence to France in 1940?

Episode 14. How Adolf Hitler turned to be a “defiant aggressor”

Episode 13. Why London presented Hitler with Vienna and Prague

Episode 12. Why did Britain and the United States have no desire to prevent WWII?

Episode 11. A Soviet Quarter Century (1930-1955)

Episode 10. Who Organised the Famine in the USSR in 1932-1933?

Episode 9. How the British “Liberated” Greece

Episode 7. Britain and France Planned to Assault Soviet Union in 1940

Episode 6. Leon Trotsky, Father of German Nazism

Episode 5. Who paid for World War II?

Episode 4. Who ignited First World War?

Episode 3. Assassination in Sarajevo

Episode 2. The US Federal Reserve

Nikolay Starikov is a Russian historian, writer and civil activist from St.Petersburg, leader of the “Great Homeland” party.

All images in this article are from the author.