Historical View of France’s Internal Problems and Unrest in Its Army

France’s defeat against Germany in the Franco-Prussian War, or Franco-German War, of the early 1870s provided stark evidence of the country’s regression. The French birth rate by this point was largely stagnating and the population of France was scarcely higher in 1870 compared to half a century before, at little more than 30 million.

French industrial capacity was trailing behind and at the time of the Franco-Prussian War France had been in decline for some decades. France was unable to recover from Napoleon Bonaparte’s ill-advised, unprovoked invasion of Russia in June 1812, which resulted in the decimation of French military forces by the more powerful and larger Russian Army.

.

The Siege of Paris in 1870 (From the Public Domain)

.

Near the time of the French attack on Russia, the Russian population was estimated to be 40.7 million, which was bigger than France’s population recorded in 1820 (30.5 million), and the Russians had greater material resources at their disposal. Russia is easily the biggest country in the world which presents a daunting challenge for an enemy force, while the Russian soldiers can be counted on to fight tenaciously, with much skill and discipline, and equipped with advanced military hardware produced by renowned manufacturers like the Tula Arms Plant.

Particularly as a result of the failed attack against Russia, France was left exhausted, shaken, and its resources diminished. France’s troubles were then compounded by being in opposition to Germany in 1870. From 1864, the German General Staff was developed by recruiting the most capable officers available. These men were highly trained, devoted to their country, and were encouraged to explore the latest military ideas.

What’s more the well-known German company, Krupp, was producing advanced weapons and was heavily supplying the German Army. Krupp would furnish German soldiers with giant siege guns like Big Bertha, which was eventually upgraded by 1918 to fire a 1-tonne shell over a distance of 23 miles; but these guns, although very powerful and impressive to look at, were quite cumbersome, slow to transport, and didn’t prove as effective as the Germans had hoped. Having a strong, professional army was a necessity for Germany. The nation’s vulnerable position in central Europe meant that in a continental war the Germans could be faced with conflicts along 2 fronts, on its western and eastern borders.

To further alleviate the threat of a 2 front war the Germans built a modern railway system, with routes running from east to west across the country. The railway lines could carry 2 army corps from East Prussia (in eastern Germany) to the Rhineland (in western Germany) in 18 hours, and vice versa. It ensured that in the event of war breaking out the German high command could rapidly deploy its troops to different battlefronts.

From the 1890s Russia was also faced with a potential war on 2 fronts should a global conflict begin. Japan’s emergence as a major power, and that country’s rivalry with Russia, meant it was not an impossibility that the Japanese would some day invade eastern Russia. In such a scenario Germany, and maybe its ally Austria, could have proceeded in a predatory fashion by attacking western Russia.

Unlike Germany, France, and Japan, Russia has had a large population and by 1890 there were an estimated 118 million Russians, a total that was bigger than any other European state and Japan. This remains the case today with a Russian population of about 150 million, while there are around 122 million Japanese, 83 million Germans, and 65 million French.

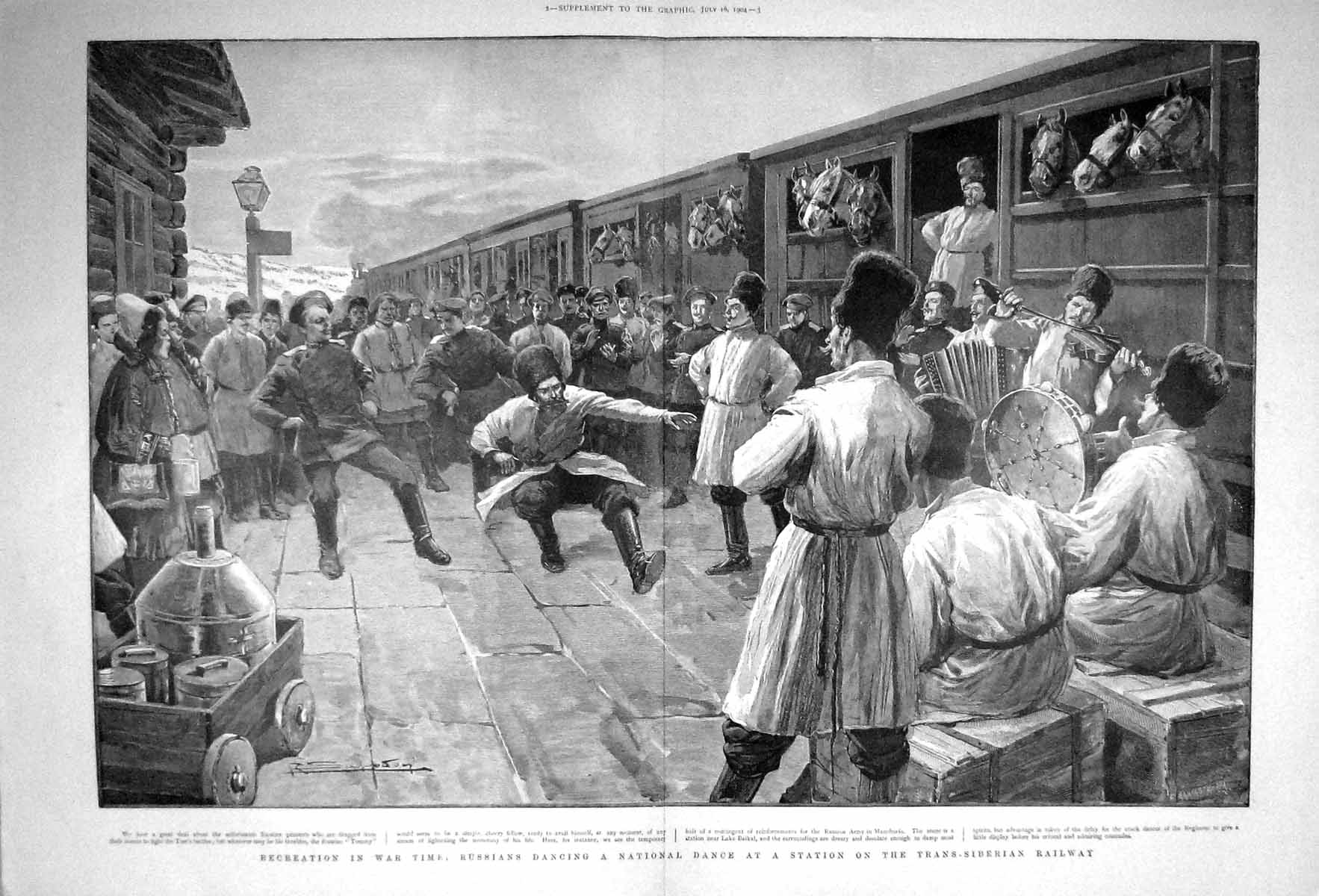

Russia has enjoyed having greater industrial capacity and resources like oil and natural gas compared to its rivals mentioned. The continued construction and expansion of Russia’s Trans-Siberian Railway from the late 19th century onward, the biggest railway on earth stretching across thousands of miles of land, was an example of Russia’s manufacturing power and innovation; and the sort of venture which the western European nations and Japan could only dream about.

.

Trans-Siberian Railway, c. 1904 (From the Public Domain)

.

Russia by itself has proven capable of winning conflicts both of a short and long duration, months or years. Resource-poor countries with populations limited in size, like Germany and France, were only capable on their own of winning wars within a short time frame. The French on their own have not triumphed in a major conflict in Europe since the beginning of the 19th century under Napoleon’s reign. Defeat against the Russians in 1812 could be excused by the French as their having been beaten by a more formidable rival. Defeat in the early 1870s to Germany, France’s neighbour and a country of similar size, was more difficult for the French to accept.

For centuries France had held the upper hand over the Germans, managing to keep German provinces like Prussia and Bavaria weak and divided by political or military measures. The tide turned with the Franco-Prussian War. The French defeat and the founding of the new German empire in 1871 drastically altered the balance of power in western and central Europe. Almost right away Germany seemed to inherit France’s claims to greatness.

This had long-lasting psychological effects on the French. In losing the Franco-Prussian War they had lost the territories of Alsace and Lorraine which the German leadership annexed to the Reich, and an inferiority complex and a hatred developed in French minds about the Germans. France’s birth rate and population continued to stagnate while Germany’s increased. In 1880 there were 45.2 million Germans and 37.4 million French. By 1890 the German population was 49.4 million while there were 38.1 million French in 1890. The gap continued growing.

What was alarming too for the French was that German industry was outstripping them. Relating to pig iron production, an important commodity in a civilian or war economy, France produced almost 1.2 million tonnes of pig iron in 1870. That same year Germany produced 1.4 million tonnes of pig iron and they increased the figure to 9.8 million tonnes by 1903. France in 1903 produced 2.8 million tonnes of pig iron.

France left to its own devices would never be a threat to Germany again; but their defeat in the Franco-Prussian War had not resulted in pacifist feelings emerging in France, nor did it for the Germans in victory, who like the French continued to believe in solving problems by military solutions if necessary. In France after 1871 army reforms were enacted, universal compulsory military service was introduced, new fortifications were built and more weapons were designed or upgraded.

Many Frenchmen longed for the return of past glories and the restoration of Alsace-Lorraine. These territories were home to a population who mostly spoke German as a first language, and the region had historical links to Germany (while after World War I there was a large pro-German separatist movement in Alsace-Lorraine between 1924 and 1929, demanding reunion with Germany, after France had retaken Alsace-Lorraine with plenty of help from her wartime allies).

Image: Napoleon after his abdication in Fontainebleau, 4 April 1814, by Paul Delaroche (From the Public Domain)

A risky, semi-mystical quality in French military thinking based on ultra-offensive tactics had sprung up following the Franco-Prussian War. Napoleon’s old saying “The moral is to the material as 3 is to 1” was much quoted and officers like Louis de Grandmaison, the chief of the Operations Branch of the French General Staff, increasingly pushed an all-out attacking war plan.

When war did break out in 1914, the French Army from the outset suffered unsustainable casualties mainly because its commanders time after time sent their soldiers on suicidal offensives across no-man’s-land, or into areas with thick vegetation where the Germans were waiting for them. De Grandmaison himself would be killed in battle in February 1915, one of numerous French officers and generals who died.

France’s gung-ho tactics played a key part resulting in the mass mutinies of the spring and early summer of 1917, nearly 3 years into World War I. The French Army was actually in the process of collapse. From April to June 1917 the French high command would acknowledge that 170 acts of mutiny had occurred during that time, of which the most severe outbreaks had involved 79 infantry regiments, 8 artillery regiments, 21 chasseur (light infantry) battalions, a Senegalese battalion, and a dragoon (mounted infantry) regiment.

The French Army rebellions were worse than Paris admitted to, involving hundreds of thousands of soldiers, and in all probability the acts of mutiny were considerably higher than 170. In the 35-mile distance between Soissons and Reims in northern France, the entire frontline was heaving with revolt. By 9 June 1917 mutinies had affected 54 French divisions. There was large-scale desertion as well, with 27,000 troops having fled to Paris alone. In the French capital city the deserting soldiers tried to conceal their identities by purchasing civilian clothes from shops beside train stations, where they had disembarked.

.

Possible execution at Verdun during the mutinies in 1917. The original French text accompanying the photograph notes that the uniforms are those of 1914/15 and that the execution may be that of a spy at the beginning of the war. (From the Public Domain)

.

Drunkenness is an example of rebellious or at least unprofessional conduct, for soldiers who are often drunk obviously can’t fight properly and in many instances will refuse to fight. Part of the problem was that alcohol was readily available to French troops, with pinard, a cheap red wine, present along the frontlines in too plentiful a supply.

The sight of drunken French infantrymen was all too common and the easy access to wine had a role in the mutinies breaking out, as did anti-war pamphlets and enemy propaganda. It was the case too that France had a disturbing number of defeatists and traitors, among them many liberals, who preferred defeat to Germany than for the war to continue.

That spring and summer of 1917, in French military formations where no mutiny was recorded by the authorities, more than 50 percent of troops returning from leave were also reporting back drunk. They must have gotten intoxicated at home, or in bars and cafes, in the hours before they returned to the front. All of this was a sign of a massive breakdown in discipline and morale.

Stern measures taken by the French high command helped to quell the insurrections, including executing the ringleaders, executing troops with the worst record of past offences, random executions as a form of intimidation, sending mutineers into no-man’s-land where they were killed by the French artillery, penal servitude for men who had committed lesser offences.

Promises were made to the French soldiers they wouldn’t be ordered to make any more suicidal attacks, that the quality of food and medical services was to be improved, and they would be allowed periods of rest. The supply of wine to the troops was curtailed though they were still allowed the occasional drink.

On 4 June 1917, when the rebellions were approaching their worst, the French war minister Paul Painlevé told the country’s leader, Raymond Poincaré, that between the German frontlines and Paris there were just 2 fully dependable French divisions, both of which were cavalry formations lacking in heavy weapons. As Poincaré and Painlevé were aware, had the Germans gone on the offensive at this time they would have won the war with ease, but they failed to attack.

The Germans did receive reports of the French mutinies. For example, 3 German prisoners who had escaped from a camp beside Fismes, 75 miles east of Paris, made their way back to German lines. They provided reliable accounts to their superior officers of a vast deterioration of discipline in the French ranks including wide-scale rioting, poor morale, the refusal of soldiers to obey orders, and drunkenness.

These reports were forwarded to the German military command but were ultimately ignored. The country’s warlord, General Erich Ludendorff, must have thought the reports were exaggerated. In any case he had set his heart months ago on pursuing a mostly defensive strategy of warfare for 1917, while building up German manpower reserves for a major offensive in the spring of 1918, approaching 4 years into the war.

From about 20 June 1917 the harsh measures of the French high command started to take effect and the unrest was dying down. It would be a partial recovery at best for the French Army. The failure of Germany to launch an attack against France in June 1917 must rank as one of history’s great missed opportunities. Had the Germans been victorious in 1917, the German empire would not have collapsed and the Nazis would never have come to power.

Britain, France’s ally, was of course aware of the rebellions afflicting the French Army. At the beginning of June 1917 the French chief of staff, General Marie Eugène Debeney, cautiously told Field Marshal Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), of widespread unrest in the French forces.

Haig was not surprised and chose to keep the news of the French mutinies a “military secret”. He decided not to inform the British government what was going on. Haig had already complained to the head of the British Army, Field Marshal William Robertson, that it was clear how the French lacked the moral fibre needed and Britain would have to shoulder the burden of the war effort.

France’s hierarchy suppressed information about the rebellions long after World War I had ended. The root causes of the discord, such as poor command and discipline, were not properly analysed and dealt with. The malady within the French Army was transmitted to the next generation of French troops, which would have dire consequences in World War II.

*

Click the share button below to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Birds Not Bombs: Let’s Fight for a World of Peace, Not War

This article was originally published on Geopolitika.ru.

Shane Quinn obtained an honors journalism degree. He is interested in writing primarily on foreign affairs, having been inspired by authors like Noam Chomsky. He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

Sources

“Big Bertha, captured by the Australians in 1918”, National Army Museum

“History of Alsace and Lorraine”, feefhs.org

“Crude birth rate in France, from 1800 to 2020”, Statista, 4 July 2024

Donald J. Goodspeed, The German Wars: 1914-1945 (Bonanza Books, 1 January 1985)

“Population of the major European countries in the 19th century”, Wesleyan University

“The Franco-Prussian War Museum at Woerth (Alsace), History of Modern France at War”, 27 September 2019

Featured image: Revue du 14 juillet 1917 [Paris] (From the Public Domain)