High Court Decision in USA v Julian Assange Extradition Proceedings. Explanatory Background Note

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @globalresearch_crg.

***

1. The High Court has today certified a question of law of general public importance, arising from the recent appeal by the US against the decision of the District Judge in this case;

“In what circumstances can an appellate court receive assurances from a requesting state which were not before the court of first instance in extradition proceedings?”.

2. We have been asked to provide a condensed explanation of the relevant history of this case before the courts and the position reached at this stage. (Attached in addition is the original defence application for three points of law of general public importance to be certified by the High Court which amplifies the legal bases on which they were premised).

3. The defence has 14 days in which to make an application to the Supreme Court for leave to appeal on the certified point.

4. In declining to give leave to appeal to the Supreme Court, the High Court is understood to be following its general practice of leaving that decision to the Supreme Court itself.

5. The background circumstances leading to the certification of the point of law above are these; a court in the UK on receipt of an extradition request has first to consider in a hearing before a District Judge at Westminster Magistrates’ Court, whether any one of a number of legal bars to extradition raised by the defence are applicable and made out in the case. If so, the Court will direct that extradition cannot take place.

6. The decision of District Judge Baraitser on January 4th 2021 came after a four-week complex evidential hearing, at the culmination of a process which had lasted a year and half, in which the testimony of a significant number of witnesses, expert and factual, was thoroughly tested. After the evidential hearing the defence and the US provided the District Judge further with extended analyses of the evidence that had been given, together with legal submissions.

7. The decision of the District Judge, based on all of the evidence explored in person and in depth before her, was that Section 91 of the Extradition Act 2003 had been made out by the defence, whereby the mental condition of Mr Assange was such that it would be oppressive to extradite him to the United States. The decision rested upon two interlinking aspects – Mr Assange’s particular mental condition combined with the prospect of the severity of the regimes he would be most likely to face on extradition. The combination of the two raised a real likelihood that faced with extradition to the US, he would take his own life.

8. After this decision in January last year, the US applied for leave to appeal, requesting the High Court to belatedly receive a number of assurances contained in a diplomatic note; these related in particular to assurances regarding the most severe categories of US custodial regimes – that they would not be imposed, unless deemed justified by some “conduct” which could include speech or unspecified behaviour. The assessment of a number of US departments or agencies could trigger their imposition.

9. The offering of the assurances, accepted by the High Court as sufficient to lift the Section 91 bar to extradition, was contested by the defence, including, it was argued, that they were inherently questionable, were caveated and/or conditional and that the history of assurances by the US showed they might be easily avoided (yet not directly breached). Further, the defence argued, when the severity of the regimes in question presented the potential of a breach of Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (prohibition on torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment), an aspect of the Section 91 bar, prohibition could never be avoided or justified by the suggestion inherent in the assurances offered that the imposition of prohibited treatment on an individual in the custody of the state, in particular one with a vulnerable mental condition.

10. The High Court found against Mr Assange in its ruling, and relied upon the late assurances, but has certified a point of law of general public importance on the question of the courts’ reception of assurances (frequently relied upon by requesting states in extradition proceedings to overcome defence evidence after it has established a bar to extradition) for the first time on appeal.

11. The identification by the High Court of the question above for the potential consideration of the Supreme Court, involves concepts of procedural fairness and natural justice. There has long been a general approach by the courts that requires that all relevant matters are raised before the District Judge appointed to consider the case in the Magistrates’ Court. What has underpinned a departure from those principles in practice is the categorisation of an assurance as an “issue” as opposed to “evidence” and the developing practice, potentially now consolidated in the decision in this case, whereby an assurance can be freely introduced by the requesting state and considered separately and later. The defence argument is that despite being as demanding of close evidential scrutiny as the evidence already heard, and despite the content of the assurances being applicable to the testimony of witnesses already heard but not to be heard again, assurances have been afforded a different procedural position. This issue has become of considerable importance in the predictability and progression of extradition cases.

12. It is therefore welcome both for Mr Assange’s case and generally that the Supreme Court might now have the opportunity of considering how and when and in what circumstances assurances may be received in extradition proceedings in the UK.

13. (The formal articulation by the defence in its application for the certified question. and the two questions on which certification had been refused, is attached). In brief, the second and third questions raised by Mr Assange, not certified as matters of general importance by the High Court, focussed upon the close relationship between the protection afforded by Section 91 of the Extradition Act 2003 and Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The defence concern remains however that the potential for treatment that is prima facie contrary to Article 3 can be triggered by any form of perceived speech and behaviour in US custody (it was accepted throughout hearings in this case that the imposition of Special Administrative Measures – the most severe categorisation of the regimes – could be triggered on the recommendation of US intelligence agencies. The overtly expressed hostility of one of these agencies in particular towards Mr Assange is a matter of record). Further, that the imposition of those regimes if judged by the US authorities to be justified, could be imposed with virtually no further explanation. The concern articulated by the defence was that this flagged up a departure from established ECHR principles.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @crg_globalresearch. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

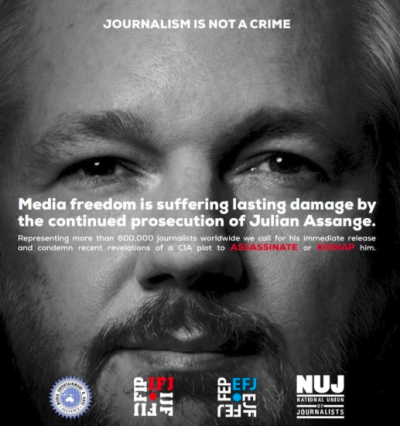

Featured image is from Don’t Extradite Assange