Head of UN Occupation Force in Haiti, Edmond Mulet, Ran Child Trafficking Network in Guatemala

Latin America is beginning to reap the fruits that it sowed in Haiti during the last decade. Its armies have become so fat as to control, either byquiet coups or default, the superficial democracies in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Peru, and Uruguay, and the outright dictatorships in Honduras and Paraguay. The most obvious consequence has been the return home to roost of the “peacekeepers”: soldiers of fortune who are so inured to urban warfare against black and brown people that they can, as part of their armies and militarized police, cheerfully participate in domestic “pacification”. Today, we have a big shot returning from the United Nations Mission for the Stabilization of Haiti (MINUSTAH), one who descends from the Guatemala of Efrain Rios Montt (1982-1983), the genocidal dictator whose sentence was annulled in 2013 after a hopeful court case turned into a project to demoralize an entire population: we have Edmond Mulet, the Assistant Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations at the UN and probably Guatemala’s next president.

On January 30, 2015, investigative journalists Pilar Crespo and Sebastian Escalon of Plaza Publica published a thorough and comprehensive report alleging that Mulet had been part of a child-trafficking operation in the early 1980s when he was a young lawyer in Guatemala taking his tentative first steps into politics. In 2010, the same report would have caused some major changes in Haiti. For one, the spotlight on international adoptions might have exposed the machinations of adoptive services, like the French “SOS Haiti”, after the earthquake, to have their governments tie emergency aid to a relaxation of controls on international adoptions, or to the legalization ex post facto of the kidnapping of children. For another, the allegations might have prevented Mulet, together with Hillary Clinton, from installing the Michel Martelly regime. The results ofPlaza Publica’s investigations were not published, however, until Mulet began to eye the Guatemalan presidency. It is already too late. Mulet will almost certainly rise to the presidency of Guatemala, where he will be well positioned to grow the country’s repressive army by expanding its “peacekeeping” operations. He might even experiment with UN nation building at home.

The 6,800-word story about Mulet’s export of children exploded after it got picked up and summarized as a Boston Globe editorial. I will not recount either the full report or its summary here but rather limit myself to the most salient points of the original report and focus on some implications that have been ignored or poorly elaborated.

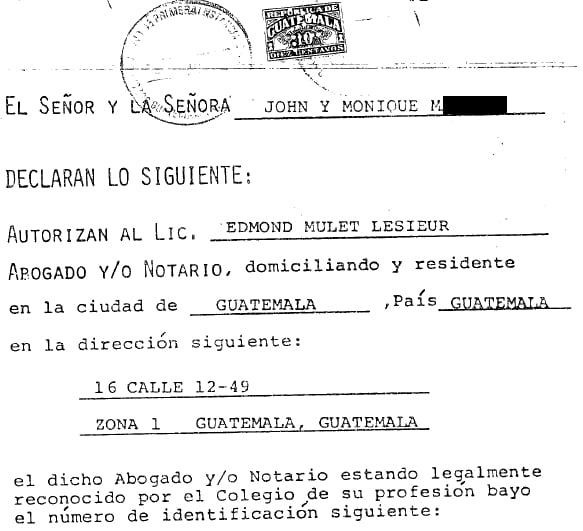

It all began around 1977, when Mulet, a 26-year-old lawyer in Guatemala, went to a party at the home of Mrs. Louise Depocas de Morel and met Jean and Lise Francoeur, a Canadian couple who had come to the country to adopt a child. Mulet and the Francoeurs immediately became such good friends that Mulet served as the witness to their “decency and integrity” for the adoption of a baby girl. Seven months after the first baby’s adoption, the Francoeurs returned for a boy from the same Guatemalan orphanage. They also became chummy with the orphanage’s director and soon thereafter founded Les Enfants du Soleil (Los Ninos del Sol, or Children of the Sun) a supposed “non-profit organization for information on international adoption.” Thus a partnership was struck in which Louise Depocas de Morel served as the president of Les Enfants du Soleil in Guatemala, Jean Francoeur as the legal adviser in Montreal, and Edmond Mulet as the lawyer and notary in Guatemala.

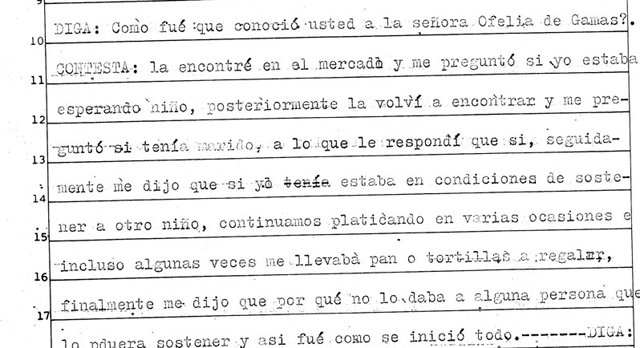

Other players in Les Enfants du Soleil and more details of its operation came to light when four Canadian women were arrested in Guatemala City’s luxurious Camino Real hotel on November 24, 1981, for intent to remove several children from the country. In the ensuing court inquiries, the testimonies pointed to a well-organized network, with a woman called Ofelia Rosal de Gamas being the person who tracked down, in the city’s parks and markets, the impoverished pregnant women who might consent to give up their children for adoption. Ms. de Gamas was the sister of General Oscar Humberto Mejia Victores, who became the de facto president of Guatemala from 1983 to 1985 and has been charged with genocide. From de Gamas, the biological mothers were turned over to a midwife called Hilda Alvarez Leal who delivered the children. Shortly after the births, the mothers were taken to Mulet’s office to sign notarized deeds consenting to the children’s adoption. Subsequently the children were taken to the Elisa Martinez State Orphanage, where they remained until the adoption proceedings were complete.

The Canadian women from the raid at Camino Real hotel had come to take away five Guatemalan children. Lise Francoeur, from Les Enfants du Soleil, and her mother, Simone Bedard, had with them two children for two adoptive Canadian couples who could not travel because of work. Another Canadian woman, Monique M. had picked up her three-year-old adoptive son and an infant of less than two months for a couple of friends; Diane W. had collected her own adoptive newborn. All the adoptive parents had initially contacted Les Enfants du Soleil in Montreal, Canada, which had advised them to hire Edmond Mulet as their lawyer in Guatemala.

In 1981, for an adoption to be legitimate in Guatemala, a social worker would have had to attest to the suitability of the adopters to take charge of a minor; the office of the attorney general (PGN) would have had to approve the adoption; two witnesses would have had to testify that the adopters were honorable and moral people; a deed of adoption would have had to be drafted in the presence of the birth and adoptive parents; finally, only after forwarding this deed to the civil registry so that the child could be renamed by the adoptive parents, would the Guatemalan immigration authorities issue a passport for the child to travel with its new parents. This process typically took about one year.

As the lawyer and notary for all five adoptions, Edmond Mulet was also arrested because he had followed none of these steps. Instead, the police investigator found five requests signed by Mulet for the issuance of expedited passports to the children. Every request gave the reason for travel as being “tourism” and the child’s address in Guatemala as being Mulet’s law firm. Apart from this, Mulet had prepared only the deed of consent of the biological parents and another document that gave the children to Les Enfants du Soleil. Mulet’s fast-track procedure for adoption took as little as two months for some adoptive parents, and the detective who interrogated him attributed to him the creation of a “system for the export of minors.”

It is noteworthy that in legitimate adoptions the new identities of the children are known to Guatemalan authorities, as well as the identities of the adoptive parents, who leave the country, together with their children, as a family. By contrast, in the Mulet adoptions, the children were shipped abroad as Guatemalan “tourists”, in fact as so many parcels, sometimes with strangers as their courriers, to become lost to all oversight from their birth country.

For various reasons, the most important one being that child trafficking was not yet recognized as a crime in Guatemala in 1981, the women from the hotel were released from jail after 15 days and the case against them was dismissed. The biological mothers were also released after a short detention. Mulet, who was then also starting his political career by running for Member of Parliament in the National Renewal Party (PNR), was freed after a single day’s detention when he brought some political pressure to bear on the police. Even a promised misdemeanor charge for acting against the interests of his clients did not see the light of day after Rios Montt came to power. One of Mulet’s major supporters then was Alejandro Maldonado Aguirre, one of the judges of the Constitutional Court that, in 2013, anulled Efrain Rios Montt’s sentence for genocide.

Mulet has expressed no remorse about his past conduct. Indeed, in a 2015 interview he argued that “If children are abandoned and there is someone who wants to adopt, educate them, give them a chance in life,… it is something to be thankful for. Adoption has saved the lives of many children not only in Guatemala, but also around the world…. Over the years, I could follow the development of these children, and this has given me great satisfaction, because if they had remained in Guatemala, orphaned, abandoned, they would have starved, had been street children, who knows what would have happened to them.” This all sounds rather altruistic, but it paints an unrealistic picture of his fast-track adoption system. It is highly improbable that Mulet could follow up on any significant fraction of the children that he had shipped to Canada and other places, given that it has been impossible even to count their number. The fact remains that the main purpose of expedited international adoptions, and the reason why some “adoptive parents” pay so handsomely for them, is precisely to dodge oversight. In such clandestine arrangements, children are not transferred to impatient loving parents by overzealous humanitarians, as Mulet would have us believe. At best, the prospective parents do not qualify in their home countries as adoptive parents because of criminal records or physical or mental disabilities. At worst, the children are transferred from one illegal network to another more nefarious ones, such as the organized-crime networks for child prostitution or even organ donation, where the newborns are used for parts and thrown away.

More than anything, this sordid story exposes the predatory “humanitarianism” of the UN mission in Haiti, which has so far treated its cases of child prostitution and trafficking as mere aberrations despite harboring alleged criminals at its highest levels. After the discovery on January 29, 2010 that Baptist missionaries had tried to kidnap 33 Haitian children during the confusion of the earthquake, then Haitian Prime Minister Jean Max Bellerive called a moratorium on international adoptions, and in an uncharacteristally ballsy move, said in a televised interview that children were being trafficked from Haiti for their organs. Around the same time, Edmond Mulet proposed instead that all adoptions should require the Prime Minister’s approval. The idea that someone with Mulet’s history could have any authority on decisions about international adoption would be laughable if it was not tragic.

The outstanding investigation by Plaza Publica will likely be of no consequence to Mulet. He cannot be convicted for acts that were not criminal in Guatemala in 1981. Furthermore, many of the main actors in the network from 34 years ago (such as the recruiter, midwife, and adoptive parents) have either died, disappeared, or signed documents to renounce all legal action against Mulet. Finally and sadly, despite these revelations, in a presidential race many Guatemalans would consider Mulet, who is famous in his country because of his prominence in the UN, to be the lesser evil.

During the past decade, Haiti has become a gathering place for the corruptible: a pasture where they are grown before being returned to their home feedlots for finishing. Given the greater incentives to investigate veteran “humanitarians” as they gain prominence, we are bound to learn a lot more about them while they make their way home to become major political players. But if they are to be neutralized, it is before they reach this stage that they must be exposed. As things stand, Edmond Mulet, an expert on misery’s stabilization, is set to promote a climate in Guatemala where the likes of Efrain Rios Montt will be comfortable. If Mulet had been disgraced in 2010 or 2011, both Haiti and Guatemala would have been spared his rule. We must do better. Truth is all well and good, but the timing of truth matters.

Sources: Haiti Chery | Documents three and five from Plaza Publica; photographs four by Johan Ordonez/AFP, six by Logan Abassi/UN/MINUSTAH, and seven by Helena Hermosa.