Haiti’s Martelly Government’s Assault on Local Journalists and Community Radio

According to the International News Safety Institute (INSI), over 100 journalists were killed in 2015, many of them by assassins. However shocking this number might be, it merely gives a glimpse into the savagery that has been unleashed against members of the press throughout the world. For one, journalists who work for small community radio stations rather than national news organizations tend to be omitted from such international counts. For another, journalists in countries with poor human rights records suffer numerous abuses, death being only the final blow.

In Haiti, where freedom of the press has been grudgingly tolerated for the last two decades or so, the latest assault on journalism began with verbal insults, like so many other abusive relationships.

The signs had been there, like the orders to shut up and veiled threats of retribution for posing the wrong questions, but on October 3, 2011 the overt public insult against a Haitian could not be ignored. Journalist Etienne Germain, of Port-au-Prince’s Scoop FM radio, a 24/7 news station, asked Michel Martelly, Haiti’s president of five months who had been handpicked by Hillary Clinton, to report his progress on forming a higher judiciary council (CSJP). First Martelly ignored the question while he answered a foreign reporter in English. Later, when Mr. Germain repeated himself and pointed out that the president had favored a foreigner over a compatriot, Martelly thundered: “Look, if you persist, I’ll insult you and your mama!” Far from regretting his behavior, a few days later, when offered a chance to explain himself, Martelly told the press: “I didn’t like the way I was approached. That’s my answer. That’s all.”

By early 2012, Martelly’s vulgar outbursts had become so commonplace that many journalists joined the other marchers in Haiti’s streets to demand, among other things, respect for the press. The insults did not stop. Martelly sank to yet new lows when confronted with questions from ordinary Haitian citizens, whom he apparently considers to be even farther beneath him.

During an election campaign rally for his political party in the city of Miragoane on July 28, 2015, when a young woman reminded him that he had not kept his previous campaign promises to the town, he rebuked her: “I came to talk to you; you must listen,” and then he added: “W$%re! If you want to have s*x, find yourself a man to !@ck you behind the wall! I’m ready to !@ck you on the podium!” as he gestured suggestively, to laughter and applause. This particular stunt caused one political party to withdraw from the barely functioning regime, which lacks a parliament. The symbolism of a Haitian president who serves a foreign occupation while he devalues Haitians, on the 100th anniversary of the first United States occupation of Haiti, was not lost on anyone.

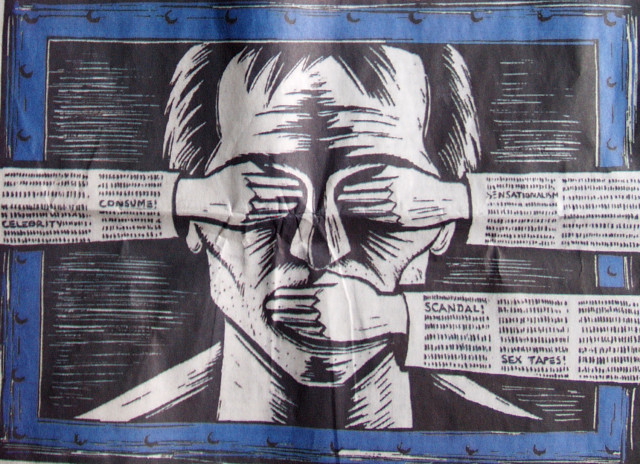

The public insults against the press have morphed into overt calls to corruption and expressions of disdain at the poverty of journalists, as if they are mistresses to be publicly humiliated and discarded from a sadomasochistic fling.

In an open letter, the national station Radio Télé Kiskeya exposed its discovery that, at a Christmas reception on December 23, 2014, Martelly offered “small informal” gifts to a select group of journalists and then referred them to his spokesman and the head of his communication’s office to be organized in single file and get handed envelopes full of cash ($1,100 for some and $870 for others) as they were being photographed. At Radio Kiskeya, three journalists who had accepted these gifts of cash were publicly sanctioned.

On November 4, 2015, the Communications Minister, Mario Dupuy, announced that the government would serve as a banker to guarantee that any journalist could buy a new car on credit and make monthly payments of only about $130. Mr. Dupuy, a career journalist who has apparently gone over to the dark side, as evidenced by his multi-thousand-dollar suit in a country where the minimum wage is about 45 cents per hour, further proposed that his office would soon recruit and train media workers to work for the government’s communication services.

Inducements to corruption and vulgar sexual insults are understandably disconcerting and an affront to polite society, but that is the least of it. The vituperations of people in power are not mere words.

They usually represent to others a license to abuse and kill the members of a disadvantaged group: in this case, dark and poor Haitians who have the temerity to presume they can address the ruling class as their equals. Indeed, Haitian journalists have become the prey of the rich and their affiliates, such as bodyguards, and the members of the foreign-trained Haitian National Police (PNH). Furthermore, a pervasive corruption and weakened judiciary combine to guarantee that the perpetrators of crimes against journalists are almost never punished. In at least one case, the president’s security detail appeared to be under orders to assault certain members of the press.

Specifically, a member of Martelly’s security corps rushed Rodrigue Lalanne, a Radio Kiskeya journalist, as he tried to ask the president a question on October 1, 2013, on the then recent Dominican constitutional court’s decision to denationalize its citizens of Haitian ancestry. Months after a clearly identified irate policeman hit Radio TV Signal cameraman Samus David François’ motorcycle with a police car in July 2015 and then beat the journalist with his tripod, the case remains bogged down in legal technicalities. After a savage beating of Radio Télé Express journalist Gerdy Jeremie by two police commandoes as she covered a moto-taxi drivers protest in November 2014, one hearing about the case was postponed because the defendants failed to appear in court, and another because the dean of a court had ordered the premises shut. After much public protest, a hearing was held, and the court ordered the policemen to pay damages, but the award hardly covered Jeremie’s bills.

In one of the most egregious cases, journalist Wendy Phèle of Radio Télé Zenith (RTZ), a station in Haiti’s Cul-de-Sac plain, had to go into hiding two months after getting shot multiple times and being left for dead on March 17, 2012 by a bodyguard of one of Martelly’s interim mayors. According to Phèle, who lost a kidney in the attack, his assailant continues to circulate freely and to intimidate residents of the town, although charges have been brought against him. Another member of RTZ, George Fortuné, was violently assaulted by a policeman in front of a higher official and then photographed as a threat, while the journalist covered a protest on November 29, 2014.

Unsurprisingly, many journalists are losing their lives in this atmosphere of impunity. Starting with the March 7, 2012 assassination of Jean Liphète Nelson, the director of the community station Radio Boukman, in the large Cité Soleil slum, from a volley of gunfire to his car, the murder rate of Haiti’s journalists during the Martelly regime has accelerated to rival those of the country’s worst military dictatorships.

At least five other journalists have since succumbed from the bullets of assassins who were probably paid to kill them. Georges Henry Honorat, the director of the weekly newspaper Haiti Progrès was killed near his home on March 23, 2013, by two shots to his head, by masked individuals on a motorcycle; about two years later, on May 26, 2015, Eddy Alcindor, a journalist, photographer and publisher also for Haiti Progrès was likewise killed in his own neighborhood by unidentified gunmen. In both cases, the assassins took none of the victim’s possessions and had clearly come only to kill them. On February 8, 2014, the human rights advocates, the couple Daniel Dorsainvil and Girldy Lareche were assassinated near their home, also by unidentified gunmen, shortly after publishing a report that described a systematic violations of human rights by the regime. On April 2, 2015, unknown armed individuals pushed their way into a minibus and assassinated journalist Marc Elie Pierre, who had worked for Melodie FM and several other radio stations. Pierre-Richard Alexandre, a correspondent for Radio Kiskeya in the city of Saint Marc, was killed a few feet from his home too, on May 20, 2013; however this case was somewhat different from the others because witnesses clearly identified the assailant, who received a five-year sentence in 2014 but appealed this sentence. None of the other cases ever made it to a court.

A major loss to Haitian radio in general was the sudden death on March 1, 2015 of Sony Estéus despite being only 50 years old and in perfect health. Mr. Estéus was a linguist devoted to Haitian Creole, the director of the Society of Animation in Social Communication (SAKS), a local organization of more than 40 community radio stations, and the Caribbean representative of the World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters (AMARC). He was also active in a popular summer university that hosted students from over 150 regions. During the January 2010 earthquake, Mr. Estéus helped Port-au-Prince’s radio stations, nearly all of which had been destroyed, to restart broadcasting. His death, just before the charade of Haitian elections, was a devastating blow to the country’s journalists. He was an especially big loss for Radio Kiskeya, with which he had collaborated for about 10 years, and where he hosted a regular show addressed especially to Haiti’s peasantry and called “nou tout anndan.” The title of the show, which means “all of us inside” was a direct commentary on the usual reference to Haiti’s rural areas as being “an deyò,” meaning outside.

It is important to understand that even a low count of journalist murders does not happen in a vacuum but a poisonous atmosphere of humiliation, harassment, threats, and routine disregard for human rights. To prevent Haitians in Haiti, the US, France, and Canada from getting real news, independent radio stations as well as their journalists are routinely subjected to legal harassments that typically escalate into threats and finally destruction. Even before Martelly’s inauguration, Tèt Ansanm Karis, a community radio station that served a Haitian city of about 10,000 residents, was destroyed by arson, possibly for having aired the results of a controversial 2011 legislative election.

Prior to its destruction on April 21, 2011, the station had received threats and therefore been able to identify its enemies. Despite warrants being issued against several individuals, they continued to circulate freely and even to socialize with the local police. Radio Monopole of the southern city of Cayes was similarly torched in an act of arson on June 27, 2012.

This happened about one month after it successfully fought an attempted shutdown by the National Telecommunications Council (CONATEL) and was forced to change its broadcast frequency. According to the station’s owner, Martelly partisans had openly criticized him for what they perceived as being hostility to the regime. In Montreal, Radio CPAM 1610 AM was burned on July 2, 2012 in a barely disguised act of arson that involved lighting fires in two parts of the station’s premises. Again, the station’s owner reported that he had received threats after criticizing Martelly. All of these cases had in common that the fires had followed threats but caused no casualties because they typically happened at night, while the buildings were unoccupied.

More recently, the intimidators of journalists have taken to attacking their work premises with automatic gunfire. Radio Zenith and Radio Kiskeya appear to be taking the brunt of these attacks. On November 24, 2015, the owner of RTZ foiled an attack by a group of identified armed individuals, and he fingered members of the police as conniving with the criminals. It hardly seems surprising that the attack followed a failed attempt by CONATEL in April 2014 to shut down the station by recalling a decree of 1977. On December 1, 2015, it was the turn of Radio Télé Kiskeya, in Port-au-Prince, to report a gunfire attack against its premises. The station’s director noted that this was the first such attack in its 21 years. In any case, the CEOs of both stations also reported that they and their staff had received death threats.

Haiti’s local press is well respected, although the US and French embassies, as well as US State Department organs, like USAID and the Voice of America, have in recent years made declarations that Haiti’s journalists are in dire need of training. A cottage industry has developed in the US and Canada, to replace genuine Haitian voices with voices that belong to the foreign press and law NGOs, in presenting the news. Many of the latter benefit directly and indirectly from grants from George Soros’ Open Society Foundation. The Open Society operates in numerous countries. It was recently banned by the Russian Prosecutor’s Office for being an “undesirable group” and a “threat to the constitutional order and national security.” In Haiti, this foundation goes by the name of Fondasyon Konesans Ak Libète (Knowledge and Freedom Foundation, FOKAL). I have already discussed elsewhere the colonialism-of-the-mind involved in having one’s journalism done by the supposedly well-meaning members of occupying powers. Though such individuals are granted greater access to some data, as evidenced by Martelly’s affection for foreign journalists, an invariable aspect of their news reports is an acceptance of the status quo. For example, in its numerous articles about Haiti’s cholera epidemic and the failures of the post-earthquake reconstruction, the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), which lists the Open Society Foundation as one of its major sponsors, has not once proposed, in a major English-language article, the removal of the UN, USAID, and other US influences from Haiti as being possible solutions to its problems. FOKAL also finances the activities of countless pseudo-journalistic social-media personalities. As the southern US proverb says, “You’ve got to dance with the one who brung ya.” One does not take Open Society money to advocate for the nationalistic removal of a US occupation.

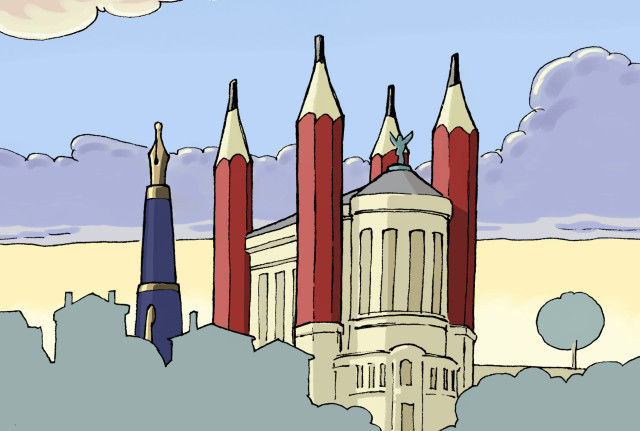

Like the media in many countries, Haiti’s press is under vicious attack, not only because it is the last rampart of democracy but also because it safeguards the population. One of the clearest recent examples of the latter function was the continued broadcasting of Radio Signal FM during the 2010 earthquake, which saved countless lives. In the subsequent days, the station’s 12 staff journalists worked extended shifts under nearly impossible circumstances, although at least one of them had lost his child and others had close family members who had died or been grievously injured. By contrast, the police and so-called United Nations peacekeepers searched for their friends, protected property, and they left the local population to fend for itself. As for the foreign NGO journalists: they were safely ensconced in their villas, hotels, and secure work buildings. However well meaning they might be, they like their salaries tax-free and landscapes seismically quiescent. They cannot be counted on to stick around for the shakeups.