Haiti – The Price of Freedom

In the days when BWIA used to fly to Haiti, I once sat next to a man who asked me to fill out his immigration form. François’ occupation was painter, and as he was about to get off the flight, he gave me an unexpected gift – one of his paintings. I’d mistakenly assumed he was a house painter. To be honest, I thought the painting rather touristy. It was a landscape, with clouds, birds, trees and houses all lined up symmetrically. Only the people were out of order.

All the same, I was touched by the gesture. The painter’s generosity far exceeded the small service I had rendered. It took me more than a decade to frame the painting which I’d dismissively set aside. I was amazed to see how the defining border transformed into vibrant art what I’d thought of as paint-by-numbers work. By investing in a frame, I’d decided that the painting was art. It makes you wonder about how perception is altered by the ways in which we frame reality.

Take, for instance, Pat Robertson’s lunatic perspective on the catastrophic earthquake in Haiti. Founder and chairman of the Christian Broadcasting Network, Robertson, a former Republican candidate for the US presidency, makes Sarah Palin look like a ‘bonafide’ intellectual. In an interview on January 13, Robertson made a preposterous declaration:

“You know, Kristi, something happened a long time ago in Haiti and the people might not want to talk about it. They were under the heel of the French. Ah, you know, Napoleon III and whatever. And they got together and swore a pact to the devil. They said we will serve you if you’ll get us free from the French. True story. And so the devil said, ‘OK, it’s a deal.’ And ah they kicked the French out. You know, the Haitians revolted and got themselves free. But ever since, they have been cursed by by one thing after the other.”

Where do you start to unravel the knots of confusion? First of all, I just love that eloquent ‘whatever.’ Wikipedia defines the slang word as “an expression of (reluctant) agreement, indifference, or begrudging compliance.” As used here by Robertson, ‘whatever’ signifies a total suspension of thought. The brutality of enslavement by the French is reduced to mindless indifference.

In Robertson’s ‘true story’, the devil and the Haitian freedom fighters become one. The devil agrees to liberate the people. But in the next sentence, Robertson uses ‘they’: “and ah they kicked the French out.” Is this ‘they’ the combined forces of the devil and the Haitian people? Or is Robertson unconsciously conceding that the people, moreso than the devil, had a hand (and a foot) in their emancipation? He does go on to say that “the Haitians revolted and got themselves free.” But that rather peculiar turn of phrase, “got themselves free”, takes us right back to the claim that freedom was a gift of the devil.

Furthermore, Robertson asserts that the price of devilish freedom is a curse. Here, this simple-minded Christian minister edges away from the lunatic fringe and right into the arms of more ‘mainstream’ analysts of the plight of the Haitian people: Had Haiti remained a colony of France, like the overseas departments of Martinique, Guadeloupe and French Guiana, how blessed the people would now be! But, no. The Haitian people dared to declare their independence. And just look at how pauperised they are.

It is still not widely known that Haiti was forced to pay 90 million gold francs in reparations to France for freedom. This vast sum is equivalent to more than US$21 billion today. Haiti had to borrow the money from French banks. Repayment of the reparations debt stretched out over decades and had a devastating impact on the Haitian economy. By the end of the 19th century, 80 per cent of Haiti’s national budget was being spent on debt repayment and interest. Sounds like an IMF agreement, a truly devilish pact.

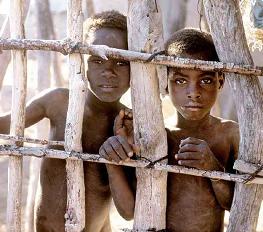

Haitians in Portmore

The US refused to recognise the new Haitian republic and imposed an embargo that lasted until 1862. In 1915, the US invaded Haiti to protect its economic interests and remained in occupation until 1934. Local Haitian leaders were no less predatory than foreign forces, as demonstrated in the truly terrifying reign of Papa and Baby Doc. But there was also the redemptive Aristide who affirmed social justice as an essential Christian principle. He was deposed in a military coup.

Crazy as Pat Robertson’s explanation for last week’s earthquake is, it’s not that different from the account I got from a man who works in construction in my neighbourhood: “Is because of all a di gun dem weh di Haitian dem a bring inna Jamaica. Whole heap a AK47. Dem exchange di gun fi ganja.” My attempt to reason with this man was in vain: “A through you don’t know. Nuff Haitian inna Portmore.”

This is a classic example of how other Caribbean people still demonise Haitians. We forget about our shared history. It was a Jamaican, Boukman Dutty, who spearheaded the Haitian Revolution. In August 1791, Boukman/Book Man, so named because he was literate, conducted a religious ceremony at Bois Caiman in which a freedom covenant was affirmed: Pat Robertson’s ‘pact to the devil.’ Whatever.

When I think of Haiti, it’s not poverty that first comes to mind. It’s the magnificent art created by these resilient people. I know that out of the rubble of this earthquake, the Haitian people will rise yet again. And they don’t need the help of the devil.

Carolyn Cooper is professor of literary and cultural studies at the University of the West Indies, Mona. Send feedback to: [email protected] or [email protected].