“Haiti is Open for Business!”: Government Complicity in Wage Theft by Foreign Factories

PORT-AU-PRINCE – Haiti’s minimum wage will nudge up 12% on Jan. 1, from $4.65 to $5.23 (or 200 to 225 gourdes) per day. Calculated hourly, it will go from 58 to 65 cents, before taxes.

But the raise will not affect Haiti’s 30,000 assembly factory workers, who are supposed to already be receiving about seven dollars for an eight-hour day – about 87 cents per hour. Recent studies have found rampant wage theft at almost two dozen of the factories that stitch clothing for companies like Gap and Walmart.

The wage hike comes almost five years after the Haitian parliament asked for a 200-gourde minimum wage, then worth $4.96 a day, but failed to overcome Washington-backed industry opposition [see sidebar].

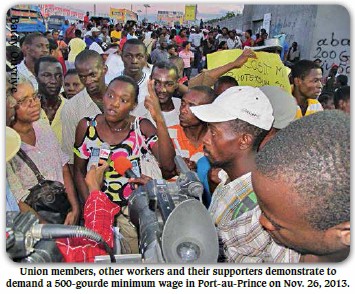

Agreed to on Nov. 29 by a government-convened Council on Salaries (CSS) – made up of labor, business and government representatives – the raise falls far short of the minimum wage of $11.63 (500 gourdes) that factory worker unions and others were demanding.

Last month, in the capital and in Haiti’s north, the Collective of Textile Factory Unions federation (KOSIT), which represents workers in three industrial parks, mobilized for the 500-gourde wage.

Picture right: Haïti Liberté

Picture right: Haïti Liberté

On Nov. 7, to chants of “500 gourdes! 500 gourdes!,” over 5,000 workers and supporters marched outside the gates of a free trade zone on the border of the Dominican Republic in Ouanaminthe. Hundreds of others marched on Nov. 26 in the capital.

The factory owners countered late last week with an open letter which pled to “keep Haiti competitive” with what they identified as their “big rivals” – Bangladesh, Cambodia, and Vietnam, countries all known for harsh conditions and abuse.

“We recognise that the clothing and assembly sectors are not ends in and of themselves, but they can be a very important stimulus and can serve as a motor to help Haiti open up and present itself as a country that is changing and modernizing,” said the 23 Haitian, Dominican, and South Korean factory owners and industrialists from the Association of Haitian Industries (ADIH).

Two days later, on Nov. 29, eight of the nine members of the CSS, including all three union representatives, approved the 225-gourde wage. (None of the union representatives were from KOSIT.)

Yannick Etienne of Batay Ouvriye (Workers Struggle), a labor group which supports KOSIT and other textile unions, said her organisation and the unions disagree with the 225-gourde salary.

“We think it is a shame that the CSS union representatives agreed to the miserable wage of 225 gourdes. At a meeting the night before, we requested that they refuse to sign any agreement that was less than 300 gourdes,” Etienne told IPS.

Rampant wage theft

Picture left: Haïti Liberté

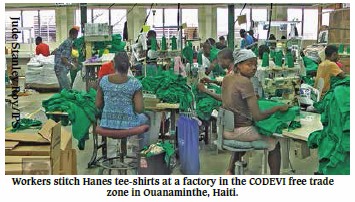

The country’s 30,000 workers – almost two-thirds of them women – in Haiti’s free trade zone assembly factories stitch together clothing for Gap, Gildan Activewear, Hanes, Kohl’s, Levi’s, Russell, Target, VF, and Walmart. Haitian law stipulates that “the price paid per production unit… must be set in a way that permits a worker to earn at least 300 gourdes for an eight-hour day.”

But recent studies by three different international groups, including the UN’s International Labour Organisation (ILO), have documented that the vast majority of workers receive the legal minimum only rarely: about 25% of the time, according to the ILO.

A 29-year-old mother who works at the Multiwear factory, which makes tee-shirts for Hanes, is one of those being gypped. (Like all workers interviewed for this story, she agreed to speak only on the condition of anonymity.)

“I support my four-year-old, and two sisters, and one brother,” she told IPS. “Sometimes I make the quota and get 300 gourdes, but just once in a while.”

In its October 2013 report, the ILO’s Better Work textile factory monitoring program found all 23 factories surveyed, including Multiwear, to be “non-compliant” with the law. To be “compliant,” Better Work said that “at least 90% of experienced workers” should be able to make 300 gourdes in an eight-hour day.

The mother is her family’s sole support. “I am the oldest,” she continued. “Right now, my husband is not working. We live in one room.”

She wants the minimum wage to be raised, but said “many people won’t even show up to a sit-in, because if the bosses think you support a wage hike, you’ll immediately be fired.”

Workers, KOSIT leaders, several reports and many economists agree that 225 gourdes, and even 300 gourdes, are not living wages.

A 2011 study by the U.S.-based AFL-CIO’s Solidarity Centre held that a factory worker living in the capital and supporting two children would need to earn about $29 per day (1,152 gourdes), six days a week, to support his or her family.

A 54-year-old worker from One World Apparel, owned by former presidential candidate Charles Henri Baker, also rarely earns 300 gourdes, she told IPS.

“When the boss started to hear talk about the minimum wage going up, he clamped down on us,” said the mother of three, who said she has worked at One World for eight years.

“You have to do 75 dozen pieces, but not every job is the same. Sometimes you can make the quota, but sometimes you can’t. No matter what the job is, the number is the same. Once in a while, if I work really hard, I can at least make 225 gourdes,” she added.

Both Gildan and Fruit of the Loom recently released statements promising to ensure their subcontractors respected the 300-gourde minimum.

“It is our view that the clear intent of Haiti’s minimum wage law is for production rates to be set in such a manner as to allow workers to earn at least 300 gourdes for eight hours of work in a day,” Fruit of the Loom said in a statement. “Based on our independent investigation, we concur with the WRC that the garment industry in Haiti generally falls short of that standard.”

In addition to denying most workers the 300-gourde minimum, bosses were regularly cheating laborers out of overtime and making them work essentially for free, according to a report from the Washington-based Workers Rights Consortium (WRC), issued Oct. 15, 2013.

In Stealing from the Poor, based on worker interviews and pay stubs from five factories (four in the capital and SAE-A at the Caracol Industrial Park), the WRC found repeated cases of employers paying workers the incorrect amount for overtime hours. (The ILO reported only 9% of factories cheating workers out of overtime.)

In the capital, WRC maintains that at the four factories surveyed – One World, Genesis, Premium and GMC – workers were “being cheated of an average of seven weeks’ pay per year.” Workers sometimes willingly work “off the clock” in order to make the quotas necessary to be paid 300 gourdes, the group reported.

Economist Camille Chalmers, director of the Haitian Platform Advocating an Alternative Development (PAPDA), is highly critical of the Haitian government for, among other things, not enforcing the 300-gourde minimum. He has called for a 560-gourde minimum wage.

“The government does not play the role of arbiter, as it should,” said the university professor while speaking at a Nov. 18 meeting on the wage issue. “Government authorities instead tend to listen to the embassies, to ADIH… Our government is really tied to the upper class, the oligarchy.”

The current government – whose slogan is “Haiti is Open for Business!” – has pushed Haiti’s low wages at numerous national and international conferences.

The mother of three agrees that the minimum wage needs to go up to at least 500 gourdes.

“If I hear there is going to be a demonstration, I’ll be there,” she told IPS. “I cannot make it with this pocket change. The bosses know that. They are just cruel.”

The recent ILO/Better Work report is the seventh Better Work report to document shortfalls and violations.

Additional reporting by Patrick St. Pré.