The Gulf Arab Dilemma: Countering Geostrategic Encirclement. Geographic Pivots of Global Trade

Despite reaping trillions in oil and gas revenue over the decades, Gulf Arabs nations have failed to construct infrastructural lifelines in any direction

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Donation Drive: Global Research Is Committed to the “Unspoken Truth”

***

The geographic pivots of global trade can be discerned just by looking at a map. Expansive landmasses, with their erratic terrains and often hostile populations, had traditionally acted as a barrier against long-distance trade and conquest. This deadlock was broken from the mid-1400s onwards when Portugal, under the helm of Prince Henry the Navigator, experienced a revolution in maritime technology and exploration. The maritime pathway was now open for the conquest of the New World and Asia.

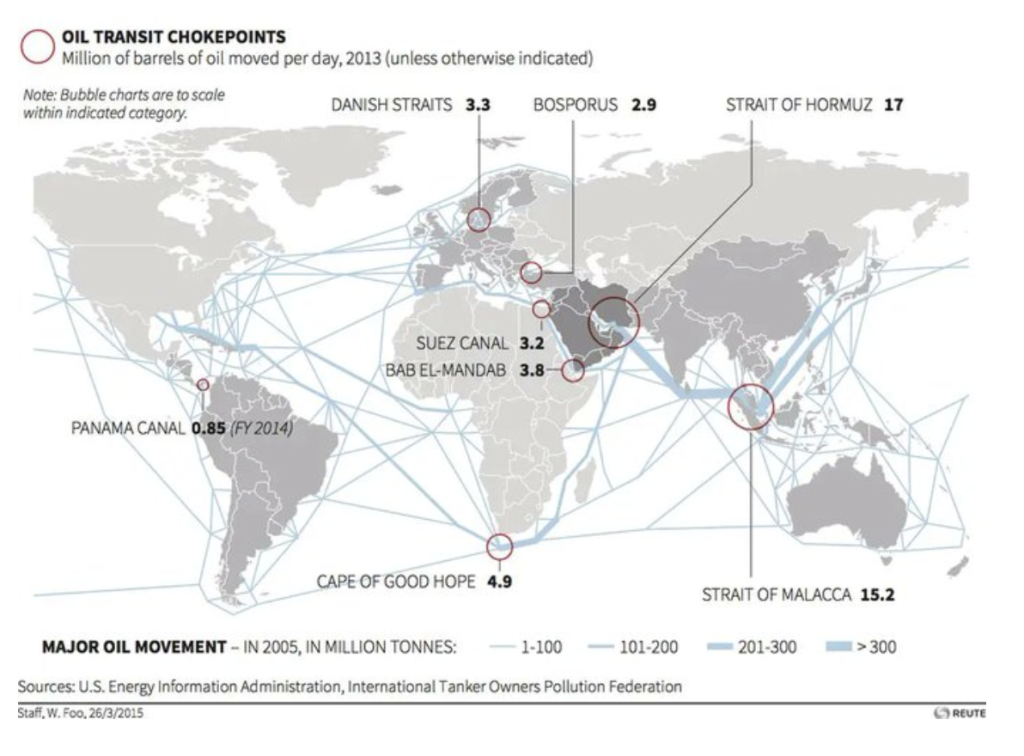

Six centuries later, despite advancements in various technologies, overland and air transport still cannot match the ease, capacity and cost-effectiveness of their maritime counterpart. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) constitutes the first overland challenge to this ancient transportational paradigm. But until the BRI meets its stated targets, over 80% of international trade will continue to be seaborne. Maritime chokepoints therefore act as the pivots of global trade.

As I had written recently, rising instability along the Red Sea, along with its twin chokepoints of the Suez Canal and Bab el Mandeb, will not upset global trade in the long run. The cardinality of a chokepoint hinges on the volume and type of trade as well as the availability of alternative routes. While the Red Sea can be bypassed indefinitely, the Straits of Hormuz remains an immovable fulcrum of global trade. Situated between Iran and the tip of Oman, it is only 33 km (21 miles) wide at its narrowest point, with shipping limited to just three kilometres. Prolonged maritime disruptions here will throw the global economy into dire straits.

While mainstream commentaries focus on the abundant flow of oil and gas out of this narrow lane, they often omit basic necessities that are shipped into Gulf Arab nations via the straits. If war breaks out between Iran and Israel, the straits would likely be closed to shipping. Oil prices will skyrocket overnight and this includes the cost of jet fuel. Airlifting basic necessities into the region would be a very expensive and dangerous proposition under this scenario. Tens of millions of migrant workers in these states, without access to state-subsidised food and water, would have to be evacuated, leaving sanitation and other essential services in a state of utter chaos.

Even the accidental sinking of a very large vessel in the Straits of Hormuz — the kind which renders the lane unpassable over a protracted period — will precipitate hyperinflationary trends worldwide.

Geographic Quagmire

For decades, Gulf Arab nations were cognizant of this existential entrapment but had failed to seek a permanent solution. Building long-term rapport, trust and infrastructure with their Arab brethren in Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq, would have given them a vital Mediterranean lifeline. Instead, under the direction of their Anglo-American overlords, Gulf Arab wealth was used to foster coups, economic subversion, an assortment of jihadi outfits, and the suppression of local autonomy in the region. Some of their actions have led to genocidal wars against the people of Syria and the Houthis in southern Yemen, to name just a few. While this internecine madness was going on, their “frenemy” Israel was gleefully annexing Palestinians lands.

It is quite telling that trillions of dollars in oil and gas revenue, stretching over decades, did not result in a single viable overland corridor from the Arabian Peninsula to the Mediterranean coastline. These corridors would have involved new roads, rails and oil and gas networks, with multiple redundancies built into the matrix. One may argue that these hypothetical networks would have been prone to periodic extortions from Levantine governments. While this argument has some merit, squabbles over transit fees are a norm just about everywhere. This is where diplomacy and compromise play a role.

If the northern Mediterranean lifeline was deemed too problematic, Gulf Arab nations could have built a southern infrastructural lifeline ending in Oman, alongside new deepwater ports. This would have permanently circumvented most risks associated with the Straits of Hormuz.

But what did they end up building instead?

Arabian Disneylands

When individuals and nations are trapped into a corner, mass irrationality is an outcome. Adolph Hitler was dreaming of a final victory even as the Red Army closed in on his bunker in April 1945.

With geopolitical tensions rising worldwide, an entrapped Gulf Arab region is similarly conjuring up its own escapist fantasies under a grand Vision 2030 plan. These entail the construction of monstrosities like The Line; a floating port city called the Oxago; a “desert sea ski resort” (yes, you read that right!) called Trojeno; and the spanking New Murabba enclave in Riyadh that will host the giant Mukaab (The Cube).

The Cube is so massive that it can reportedly house 20 Empire State buildings inside. All these will be built by 2030 at the cost of trillions of dollars. And they will be totally reliant on foreign consultants. From the perspectives of systems science, socioeconomic benefits, energy consumption and maintenance, among others, these Arabian Disneylands are disasters waiting to happen. The United Arab Emirates is set to join this construction frenzy with the Dubai Circle, a spacey floating structure that will ring the world’s tallest building, the Burj Khalifa.

The future however cannot be built without basic and secure foundations. When the Burj Khalifa was built, it had no outward sewerage system for the seven tons of human waste, and an additional eight tons of wastewater, that were disgorged each day. A daily convoy of poop trucks were used to ferry out the excreta, much of which were dumped in the desert. This earned the Burj Khalifa the moniker of “Temple of Poop”.

The situation is hardly better in Saudi Arabia. Nearly 40% of Saudi households, and 85% of Jeddah city in particular, are not connected to a centralised sewage system. Accumulated wastes in Jeddah are often dumped into the nearby Buraiman Lake (aka the Poop Lake). As a result, periodic freak flooding generously recycles these wastes across the city.

It is not an exaggeration to say that between its Third World infrastructure and lofty sci-fi dreams, Gulf Arab nations have a continental-sized, sewage-filled chasm to bridge.

Right across the Straits of Hormuz, survivalism has triumphed over escapism.

Iran has invested in sectors that are vital to its long-term survival.

These include the development of software, construction (particularly bunker) and asymmetric weapons technologies. Russia is reportedly a top customer for Iranian drones and ballistic missiles. Iranian cars are set to be exported to Russia and Belarus in the near-future.

With Indian assistance, Iran has also developed the oceanic port of Chabahar in the Gulf of Oman which not only sidesteps the Straits of Hormuz but acts as a “golden gate” to Central Asia as well. If Chabahar is destroyed in the event of a wider Middle Eastern war, and if the Straits of Hormuz is simultaneously rendered impassable, Israel’s friend India will reel from the consequences.

China, which built the nearby Pakistani port of Gwadar as an alternative to Chabahar, may not fare any better as fossil fuels will be in short supply. This is a cardinal reason why both India and China are defying international sanctions to buy up Russian oil and gas, thereby cementing their long-term designations as “friendly nations” to Moscow.

Belated Southern Corridor

A US-Israeli plan to relieve the Gulf Arab region of its geopolitical encirclement was floated by then US President Donald Trump in 2020. The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) was envisaged to link the Gulf Arab region to the wider world via an ambitious web of roads, railway lines and submarine cables as well as ports located in Oman and Israel. Officially, the IMEC was about countering China’s expanding Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) while simultaneously fostering rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Israel. The real purpose however was to neuter Iran’s stranglehold over the Straits of Hormuz.

The IMEC would have complemented the proposed Arab Mashreq International Road Network which connects Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, Kuwait, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, UAE, Oman and Yemen. However, apart from a sparse Wikipedia page, not much is known about the current status of this project. Thanks to Western and Gulf Arab meddling in recent years, parts of Syria and Iraq are off-limits to traffic.

Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza, which has resulted in more than 30,000 Palestinian deaths thus far, has just thrown a geopolitical spanner into the IMEC wet dream. The Arabian Disneyland extravaganzas however remain on track.

Ultimately, the Gulf Arab world is left with two choices in a world fraught with rapidly aggregating risks. They can either seek permanent rapprochement with Iran and thereby minimise risks in the Straits of Hormuz once and for all, or they can allow US and Israel to set them on a destructive collision course with their northern neighbour and the wider world. My bet is on the latter course of action. The Sunni Islamic world is led by dispensable pawns in the Western geopolitical chessboard.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Dr. Mathew Maavak, who researches systems science, global risks, geopolitics, strategic foresight, governance and Artificial Intelligence. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.