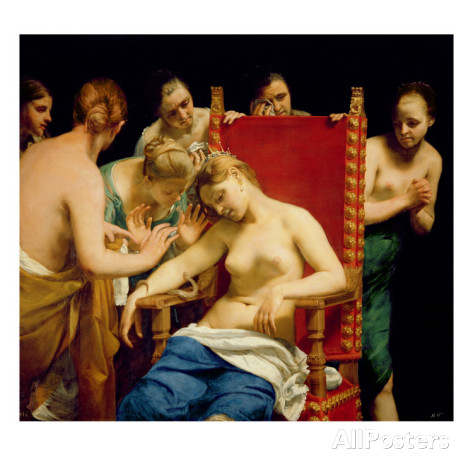

Guido Cagnacci’s “Death of Cleopatra” (c. 1645) in New York

Guido Cagnacci, whose contemporaries called “il genio bizzaro” (the bizarre genius), has by all accounts been slow in receiving the attention his work merits. Right now in New York City, three major works by the painter can been seen, just a short walk from each other.

In early 2016, The Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired Cagnacci’s The Death of Cleopatra (c.1645). While still a young man in Bologna, Guido began to paint half-length female figures, a form that would in time become a specialty of his; of these, the Met’s Cleopatra is among the finest. While the theme was a familiar one among Baroque painters, the frank sensuality and naturalism of Cagnacci’s depiction is something altogether new.

The queen’s head is tossed back, an attitude that Cagnacci would repeatedly employ. She pulls down her shirt to expose her left breast, while with her other hand she holds an asp being guided towards her heart. This picture, along with the other two later masterpieces currently on exhibition in New York City, are highly subversive works in terms of their unabashedly erotic energy, which continues to feel startlingly modern.

Born in Santarcangelo di Romagna in 1601, Guido Cagnacci studied his craft in Bologna – likely serving as apprentice to the elderly Ludovico Caracci – and made visits to Rome, where he would discover the work of Caravaggio, and adopt the practice of painting directly from live models. ‘Restless and unruly,’ Cagnacci is known to have traveled with his mistresses disguised as men so as to avoid public scrutiny – and they were likely to double as his models for such subjects as Cleopatra and Mary Magdalene.

Born in Santarcangelo di Romagna in 1601, Guido Cagnacci studied his craft in Bologna – likely serving as apprentice to the elderly Ludovico Caracci – and made visits to Rome, where he would discover the work of Caravaggio, and adopt the practice of painting directly from live models. ‘Restless and unruly,’ Cagnacci is known to have traveled with his mistresses disguised as men so as to avoid public scrutiny – and they were likely to double as his models for such subjects as Cleopatra and Mary Magdalene.

The Cleopatra Morente (Dying Cleopatra, c. 1660-63) currently on display at the Italian Cultural Institute is perhaps the greatest realization of a single figure in Cagnacci’s oeuvre. The picture dates to the painter’s final years in Vienna, during which he seems to have been at the height of his artistic faculties. Once again, the queen’s head is tilted back, but the effect is quite different. The Met’s Cleopatra could almost be a sacred painting of a saint or martyr, with her flushed eyes gazing heavenwards – indeed, there is a marked similarity in her features to Cagnacci’s own St. Anthony of Padua Preaching (c. 1641). Now, Cleopatra’s eyes are half closed and gazing under heavy, and reddened lids, outward, towards us, the viewer. If it were not for the half hidden asp, its barely visible tongue licking the air, she could be in an opium-induced state of ecstasy.

Nude from the waist up – having pulled down her white shirt to reveal a fleshly, buttery torso – this Cleopatra is utterly present in her physicality and at the same time she has absented herself, as if she knows something we do not. She is alive but beyond the living. This is a death which is anything but to be feared. “The Stroke of death is as a lover’s pinch, / which hurts, and is desired” (Shakespeare, Anthony and Cleopatra, V.ii.295-296). In her final moments, both in Shakespeare and in Cagnacci, Cleopatra erotically embraces death: invoking both the idea of the orgasm as dying, as well as the orgasmic effect of death itself (“Husband, I come!” V.ii.287).

When I went to visit her at the Italian Cultural Institute there was no one else present: she was alone in an empty room – as she is in the painting itself. Perhaps that is why it seemed to be entirely right: as if I had had just happened in upon her slumped in that large red leather chair, needing nothing and no one, utterly imperious in her solitude.

The Repentant Magdalene (c. 1660-63), on display at the Frick Collection, thanks to a loan by the Norton Simon Museum, is perhaps Cagnacci’s greatest masterpiece. It belongs to his Vienna years, and was commissioned by the Emperor Leopold I, who asked that Cagnacci “promise to make him a painting of the repentant Saint Mary Magdalene, with four full-length figures.”

The scene is set in an aristocratic residence where Mary, the wealthy courtesan, has just discarded her luxurious clothes and jewels; her hands are clasped together around a gold necklace that she grasps as if it were a rosary. Sitting before her on a red and gold damask cushion is her sister Martha gesturing towards the two allegorical figures on Mary’s left: a winged, androgynous angel (representing Virtue), clutches with both hands a long rod, ready to strike a horned demon (or Vice) as he hovers in mid-air, his lengthy, slender tail literally between his legs. The demon, angrily biting his finger, makes ready to flee, perhaps out of the window at the top left corner.

Cagnacci’s fiend might naturally be seen, given the context, as representative of the Vice of sexual promiscuity. Mary has removed her finery in a gesture that outwardly signifies the rejection of her sinful life as a courtesan. On the other hand, she is barely covered and her moist eyes and blushing face have an undeniably erotic inflection. As Xavier Salomon points out in his invaluable book, The Art of Guido Cagnacci: “regardless of how pious his paintings may be in subject, they have a highly voyeuristic impact.”

The Frick’s permanent collection includes one of Titian’s portraits of Pietro Aretino (1492-1556) the Italian poet, satirist and blackmailer – and author of L’umanita di Cristo (The Humanity of Christ, 1535), a retelling of the life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels. This book was a ‘bestseller’, especially popular in northern Italy, and the likely source for the scene depicted in Paolo Veronese’ The Conversion of Mary Magdalene (c. 1548), an event which is not described in the Bible. Martha, already a Christ follower, urged her sister Mary to go to the temple to hear Christ preach: her conversion is the result of the encounter with Jesus in the temple. Cagnacci’s Repentant Magdalene is the scene that presumably immediately follows the conversion: emotionally overwrought, Mary returned to her room, disrobed and threw her jewels and garments on the floor. The scene of Mary repenting is not described in the Bible – it too is derived, at least in part, from Aretino’s narrative.

Is it possible that Cagnacci had also come across Aretino’s, The School of Whoredom, perhaps during his eight-year sojourn in Venice, beginning in 1650? When we see Mary’s finery, and those exquisite turquoise sandals (that pinched her reddened toes), we know that this is a consummate professional. Might we not be reminded of Aretino’s satirical play, in which Nanna teaches Pippa, her daughter, that whoredom is an art as well as a craft? Its skills have to be mastered: the successful courtesan is also an actress. Attention is to be paid to language, clothes, appearances, as well as behavior, power games, social positioning, etc. “becoming a whore is no career for fools…”

Like Pippa, we could see Cagnacci’s Mary being taught and ultimately mastering the art of, “flattery and deceit.” In this light, Mary’s repentance is about not only the sinfulness of her lascivious past; but also the sinfulness of worldly ambition, of gathering treasures in this world, rather than storing up treasures in heaven.

“Those who love their life in this world will lose it, those who care nothing for their life in this world will keep it…” (John12:25). The pearls, the golden earrings and bracelets, the sumptuous blue fabric and sandals that lie strewn about on the floor (an unbelievably exquisite still-life) are the physical reminders of the life that Mary is abandoning. That we are witnessing a kind of death-in-life is evident from the servant girls as well, who seem to be aware that their mistress is, in a sense, no more: one of the girls, already crossing the threshold to the balustrade looks over her shoulder as if she is looking upon her mistress for the final time.

The three paintings by Cagnacci, which New York City has been lucky enough to host, share not only the artist’s tendency toward ‘sensuous realism’, but also his fascination with the intertwining of the earthly and the spiritual, his unique and sometimes disorienting confluence of religious and erotic longing. At the same time, Cagnacci is clearly interested in transformation, with the passage from one state of being into another – a movement that does not occur without a certain violence. Spiritual rebirth, in Magdalene, is presented not as something given, finished and done with – but as an event which is still unfolding and is anything but peaceful.

As viewers, we stand on the verge of the critical moment: the ultimate victory is foreseen but not foregone. We are on the threshold of new life – and as if to ensure we do not forget: on the ledge of the balustrade stands a terracotta pot with a carnation plant that is yet to bloom.

Dr. Sam Ben-Meir teaches philosophy at Eastern International College. His current research focuses on environmental and business ethics. [email protected]

Web: www.alonben-meir.com