Growing Your Own Food: Permaculture, Integrative Organic Farming and Gardening

Review of Meat: A Benign Extravagance by Simon Fairlee (2010, 322 pp.); and Sepp Holzer’s Permaculture: A Practical Guide to Small-Scale Integrative Farming and Gardening by Sepp Holzer (English version 2011, 232 pp.)

While the Bush reign may be described as a war on privacy, Obama’s is clearly a war on food freedom.* As his Monsanto administration arrests organic farmers and distributors, seizing and destroying healthy foods privately contracted and sustainably grown, this tyranny is not unique to the United States. All over the world, organic, sustainable farmers are under attack by large agribiz actors who, through government and trade agreements, are regulating them out of business and destroying the environment in the process.

Two farmers arguing against ecocidal hyper-regulation and “conventional” and “orthodox organic” farming are Simon Fairlee of England and Sepp Holzer of Austria. Both have written seminal books that should grace the bookshelves of everyone who gardens, farms or cares about the impact of agriculture on the biosphere.

In Meat: A Benign Extravagance, Simon Fairlee successfully proves that animal husbandry must be part of any sustainable farm, but used under a permaculture system (that which mimics nature) – beyond organic. “Permaculture” is short for “permanent agriculture” – agricultural ecosystems that are designed to be self-sustaining. It practices natural anarchy.

Ohio farmer Gene Logsdon, who authored Holy Shit and The Contrary Farmer, wrote the forward to Benign Extravagance. In it, he agrees that food security “is being undermined by well-intentioned people of all persuasions who are demanding rules and regulations in food matters without enough knowledge.”

The use of animals for sustainable farming has long been supported in the alternative ag field. What’s new is Fairlee’s stunning conclusion that animals protect against greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs), turning expert conclusions on their head.

He doesn’t reach this conclusion easily, and he agrees that fewer food animals are needed, but his research exposes the gross exaggerations made by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), oft-repeated in the vegan world. Instead, he finds that animals are being scapegoated by fossil-fuel users. To reduce GHGs, he charges logically, reduce fossil fuel use.

Though it focuses on the environmental ethics of raising animals, Benign Extravagance also chronicles the historical move away from a pastoral society to urbanized stockyards and monocultured farms that spread for miles. Today’s industrialized ag system has separated animals from vegetables, with a result of too much animal waste concentrated in one place, and not enough fertilizer in the other. This bifurcation creates toxic ponds at one end and the need for oil-based synthetic fertilizer and pesticides, as well as fossil-fuel using machinery, at the other.

An interesting tidbit reveals that Wall Street got its name because, at the time, imported pigs roamed free on Manhattan island, requiring a stockade to keep them off the farms. If only it were just as easy to keep the piggish banksters out of food speculation. Other tidbits include how the tsetse fly and the Bubonic Plague guided which animals and crops were raised where.

Fairlee postulates that the interests of agribiz and vegans will converge over lab-cultured meat and spends a little time bewailing transhumanism – a genetically and technically altered human.

Much of the vegan debate for no animals centers on the inefficiency of land use in growing food to feed the stock animals. The oft-quoted and, he shows, erroneous figure is 10:1 – the amount of nutrients in animal meat compared to vegetables.

But when adding in food miles, the need for synthetic fertilizer, pesticides, and fossil-fuel machinery on farms that don’t use animals, and when subtracting the opportunity cost for secondary use of cattle in the trade of hides, value-added dairy products, plus the hard-to-calculate value of warmth and companionship provided by farm animals, the real efficiency figure is 1.2:1, he calculates.

“Food miles may not be over-extravagant in their energy use [accounting for about 10-15% of GHGs], but they are thickly implicated in a centralized distribution system.” It is in a decentralized system that food security is increased and GHGs are reduced.

His calculations and arguments span several chapters. Two refute the absurd and deceptive FAO claim that cow farts account for 18% of GHGs. Fairlee holds his own on this argument, but probably would have appreciated having Olivier De Schutter’s report, Agroecology and the Right to Food, which was published later. De Schutter is the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food who rejects industrialized farming, instead showing how small, mixed farms provide more food and improve the land.

Among numerous sources, Fairlee also availed himself of information at EatWild.com, a site for “rational grazers,” as well as Joel Salatin’s theories and Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma.

Part of his equation acknowledges that the world’s subsistence farmers – who are primarily women – all use animals to boost farm productivity (via manure), as draft animals instead of tractors, and to enhance their family’s food security by providing secondary products like eggs and milk, along with other value-added products. And, he points out, herding also saves the world’s landless nomads from starvation.

“While meat is a luxury of the rich, it is a necessity of the poor,” he writes. “Sixty percent of all rural households in poor countries keep livestock.”

Those who want to skip the statistical arguments and exposure of deceptions used to promote industrial farming should not miss Chapter 15: The Great Divide. It is here that an overview of the meat vs. vegan debate is laid out and cemented in common sense. Whether they are aware of it or not, vegans promote factory farms by opposing livestock.

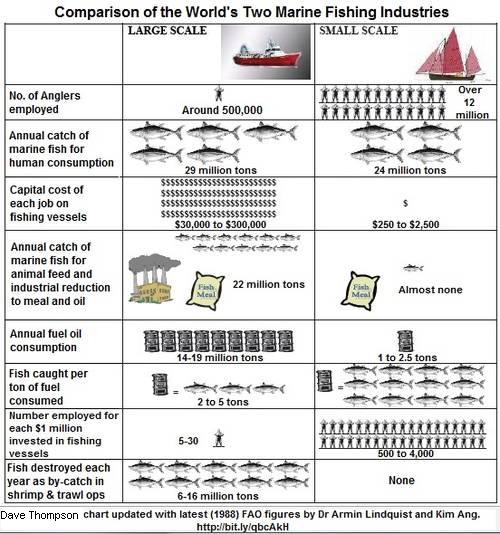

Another paradigm shift he urges involves the concept of the “Tragedy of the Commons” that he refutes with the “Tragedy of Technology,” which is solely to blame for depleted ocean stocks. One fascinating chart reproduced in the book was originally prepared by David Thompson of the FAO, who exposed the gross inefficiency of industrial fishing compared to small fisheries. Below is a slightly updated version:

His final chapter details his vision of a permaculture economy where he sees more trees, fewer animals and a re-ruralized society. While much of his book is written with humor, and readers shouldn’t miss his continual references to GOOFs – global opponents of organic farming – it is this last chapter that reveals Fairlee’s genius.

He convincingly argues that famine is not caused by “inefficient animal husbandry displacing efficient” farms. “The conflict” he says, “arises when symbiotic land use is usurped for monoculture designed for export.”

Sepp Holzer couldn’t agree more. He has been described as the “European counterpart” to Australia’s Bill Mollison and Japan’s Masanobu Fukuoka – “as all three independently discovered ways of working with nature that save money and labour and that don’t degrade the environment, but actually improve it.”

In Sepp Holzer’s Permaculture: A Practical Guide to Small-Scale Integrative Farming and Gardening, he provides practical hands-on instruction with a caveat: Each permaculture system is unique. The gardener or farmer must understand all the factors that go into completing a self-sustaining ecosystem, including water, wind, sun, soil, wildlife and terrain, as well as climate and nearby pollution sources that impact all of this.

His 110-acre alpine farm in Austria sits between 3,300 and 4,900 feet in altitude (1,000-1,500 meters). It supports 10,000 fruit and nut trees, 30 different types of potatoes, a variety of grains, mushrooms, vegetables, herbs and wildflowers, as well as domestic and wild cattle, pigs, chickens, introduced snakes and even alpine crocodiles at one time.

“Once planted, I do absolutely nothing,” Holzer told Reuters. “It really is just nature working for itself – no weeding, no pruning, no watering, no fertiliser, no pesticides.”

Having practiced his own brand of permaculture for 50 years, he knows of what he speaks.

Instead, he modified the landscape with terraces, giant stone slabs, and over 70 ponds to direct wind, water, solar energy, and the terrain to permanently support the system.

Not one square meter of Holzer’s ground hosts only one type of plant. Starting from the age of five, he learned that as plant variety increases, parasites are reduced and the ecosystem becomes stable.

As an adult, he realized that most of what he learned in agriculture college and books was destroying the farm he inherited from his parents. He rebelled.

His autobiography, The Rebel Farmer, chronicles his battles against ignorant regulators whose rules were destroying his farm. He has fought regulatory agencies for decades, being mired in litigation and fined several times, and threatened with imprisonment. One example that cost him in fines involved his refusal to prune his trees as regulated.

He noticed that the only apricot tree faring well during the winter, where temperatures can drop to -29 °F (-34 °C), was the one he had not pruned. The length of the uncut branches allowed them to droop enough to touch the ground, providing support while the snow slid off. The branches of the pruned trees broke under the weight of the snow, killing the trees.

Sepp Holzer’s Permaculture is filled with photos, diagrams and detailed instructions on every aspect of his mixed-farm system that increased his wealth and the quality of his land. It exemplifies “beyond organic” by mimicking nature in every aspect from natural roads and buildings to natural pesticides (like his homemade bone salve used to protect his trees) to companion plants to vermiculture, and much more.

Instructions aren’t limited to large farms, either. He describes and diagrams balcony gardens and small town gardens that can feed families or whole neighborhoods. And, of course, his theories apply to both farms and gardens.

Nearly everything he does is different from what most of us learn – even how to plant trees. Most of us buy a small tree with a root ball covered in burlap, but his are square with companion plants at the base of the tree. Among several free videos of or about Holzer’s techniques, this one is probably best.

One thing is clear from his book; Holzer would never farm without animals, as they are a part of the play of nature.

“Livestock play a large role in a permaculture system; they do not just provide high-quality produce, they are also industrious and pleasant workers…. The animals actually work for me by loosening the soil and tilling my terraces.” And, they bring the added fertilizer in the form of manure.

Like Joel Salatin on his Polyface Farm, Holzer rationally grazes his animals on various paddocks to ensure no one spot is over- or under-grazed. He also grows poisonous plants because he’s observed that animals suffering from diarrhea will deliberately eat them. He no longer has to worm his animals.

“The fact that it is actually necessary to become a ‘rebel’ to run a farm in harmony with nature is very sad!”

Many would agree. The joy comes in practicing a holistic approach when growing your own food, he says, giving you independence and healthy foods from an environment that is enriched rather than depleted. It is this very anarchy that will save the environment and feed the world.

Rady Ananda specializes in Natural Resources and administers the sites Food Freedom and COTO Report.

* Here’s a small sampling of articles revealing hyper-regulation:

Georgia cops bust 10-year-old’s lemonade stand

Michigan woman fined for growing veggies on her front lawn

Georgia farmer fined $5K for growing too many veggies

Kentucky Food Club defies illegal Cease and Desist Order from Health Dept

Elderly Man Evicted from His Indiana Land for Living off the Grid

UK family living off the grid evicted from their own land

Australia proposes ban on 1000s of plants including national flower

Urban garden that grosses $2,500 must buy permit for ‘several thousand dollars’