Great Powers and Global Politics

Terminology

A meaning of the term Great Power(s) (GP) in global politics from the beginning of the 16th century onward refers to the most power and therefore top influential states within the system of the international relations (IR). In other words, the GP are those and only those states who are modelling global politics like Portugal, Spain, Sweden, France, the United Kingdom, united Germany, the USA, the USSR, Russia or China. During the time of the Cold War (1949−1989) there were superpowers[1] as the American and the Soviet administrations referred to their own countries and even a hyperpower state – the USA, after the Cold War as it is called in the academic literature.[2] A focal characteristic of any GP is to promulgate its own national (state’s) interest within a global (up to the 20th century European) scope by applying a „forward“ policy.

A term global politics (or world politics) is related to the IR which are of the worldwide nature or to the politics of one or more actors who are having global impact, influence and importance. Therefore, global politics can be understood as political relations between all kinds of actors in the politics, either non-state actors or sovereign states, that are of global interest. In the broadest sense, global politics is a synonym for global political system that is “global universe of actors such as nation-states, international organizations, and transnational corporations and the sum of their relationships and interactions“.[3]

Characteristics

Originally, in the 18th century, the term GP was related to any European state that was, in essence, a sovereign or independent. In practice, it meant, only those states that were able to independently defend themselves from the aggression launched by another state or group of states. Nevertheless, after the WWII, the term GP is applied to the countries that are regarded to be of the most powerful position within the global system of IR. Those countries are only countries whose foreign policy is “forward“ policy and therefore the states like Brasil, Germany or Japan, who have significant economic might, are not considered today to be the members of the GP bloc for the only reason as they lack both political will and the military potential for the GP status.[4]

One of the fundamental characteristics and historical features of any member state of the GP club was, is and will be to behave on the international arena according to its own adopted geopolitical concept(s) and aim(s). In other words, the leading modern and postmodern nation-states are “geopolitically“ acting in the global politics that makes a crucial difference between them and all other states. According to the realist viewpoint, global or world politics is nothing else than a struggle for power and supremacy between the states on different levels as the regional, continental, intercontinental or global (universal). Therefore, the governments of the states are forced to remain informed upon the efforts and politics of other states, or eventually other political actors, for the sake, if necessary, to acquire extra power (weapons, etc.) which are supposed to protect their own national security (Iran) or even survival on the political map of the world (North Korea) by potential aggressor (the USA).

Competing for supremacy and protecting the national security, the national states will usually opt for the policy of balancing one another’s power by different means like creating or joining military-political blocs or increasing their own military capacity. Subsequently, global politics is nothing else but just eternal struggle for power and supremacy in order to protect self-proclaimed national interest and security of the major states or the GP.[5] As the major states regard the issue of power distribution to be fundamental in international relations and as they act in accordance to the relative power that they have, the factors of internal influence to states, like type of political government or economic order, have no strong impact on foreign policy and international relations. In other words, it is of „genetic nature“ of the GP to struggle for supremacy and hegemony regardless on their inner construction and features. It is the same „natural law“ either for democracies or totalitarian types of government or liberal (free-market) and command (centralized) economies.

Categorization

Power differs very much from one state to another likewise of the same state from historic perspective. Generally, the most powerful states enjoy and the most influential impact on international affairs either regional or global and control the majority of the power resources in the world. In practice, only several states have any real influence on global IR while the other states can have an influence just beyond their immediate locality. These two categories of states are named as the GP and the Middle Powers (MP) in the international system of intra-state relations.[6] A status of the GP can be formally given and to some supranational structures like in the 19th century to the Concert of Europe or in the 20th century to the UNO, the NATO or the Warsaw Pact.

Nevertheless, the fundametal division of the world states according to their impact on global affairs is just into two basic categories:

- The category of the GP (several top-powerful states).

- The category of non-GP (MP and low- or non-influential states).

A GP state is such state that is considered to be a member of the most powerful and influential group of states in a hierarchical order of the world state-system. Today, this term is related to the state that is regarded to be among the most powerful states in the global political system.[7]

The most problematic issue in categorization of the states within the world state-system is applied criteria. Nevertheless, the criteria which define one state to be or not to be a great power is usually, at least from the academic point of view, of the following basic ten-point conditions:

- A GP state is such state that is on the top-rank level of military power, having the real capacity to protect and maintain its own security and to influence the politics of other states or other actors in international relations.

- A GP state is a state that can be defeated militarily only by another member of GP club or by alliance of some of the states coming from this club.

- A GP state is from the economic perspective a powerful state. This condition is a necessary but, however, in some cases (like today Japan or the USA at the time of its isolationist period of foreign policy) is not and sufficient condition for the GP status. This is a quantitative condition for the status of a GP. The other quantitative conditions are certain level of GDP, GNP or GNI[8] or the size of its armed forces. The economic conditions can be and of qualitative nature like a high level of industrialization or the capability to make and to use nuclear weapons.

- A GP state has rather global, but not merely regional or continental, spheres of influence and interest. It means that a GP is such state that possesses, exercises as well as defends its own whatever interest throughout the globe.

- A GP state has to be at the front rank in regard to its military power and therefore it has to enjoy both certain privileges and duties dealing with global peace and international security.

- What is probably the most important, a GP state adopt and apply a “forward“ foreign policy having rather actual but not only potential impact on international affairs and other states or group of them. It practically means that a GP state can not adopt a foreign policy of isolationism.[9]

- The members of the GP club tend to share a global outlook that is founded on their own national interests far from their homes.

- The GP have strongest military forces and strongest economies to support their GP status.[10]

- The GP cannot easily lost its status in IR even after heavy military defeat due to its size, manpower and long-term economic potentials.

- The GP form alliances with smaller and weaker client (quisling) states.[11]

A GP status to some state can be and formally recognized by the international community as it was the case by the League of Nations in the interwar time or by the United Nations Organization (UNO) after the WWII up today (five veto-rights permanent member states of the Security Council – China, Russia, France, the USA and the United Kingdom). A GP status of these five “extraordinary“ members of the UNSC is guaranteed by their practice of unanimity. In other words, a concept of the GP unanimity holds that on all resolutions and/or proposals before the UNSC, a veto by any one of these five (privileged) states can be used that practically means that one GP state can block further work of the UNSC on certain issue.[12] Undoubtedly, one of the critical features of any GP state is its power projection that is a considerable influence, by force or not, beyond state’s borders, i.e. abroad, that less powerful countries could not match (for instance, the NATO military aggression against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1999 conducted in fact by the USA).

The GP states are inter-connected within a Great-Power System that is the set of special relationships between and among this privileged club of the post powerful global actors in IR. Those special relations are conducted by their own rules and patterns of interaction as the GP have very extraordinary way of behaving and treating each other. This special way is, however, not applied to other states or other actors in global politics and system of IR.

History

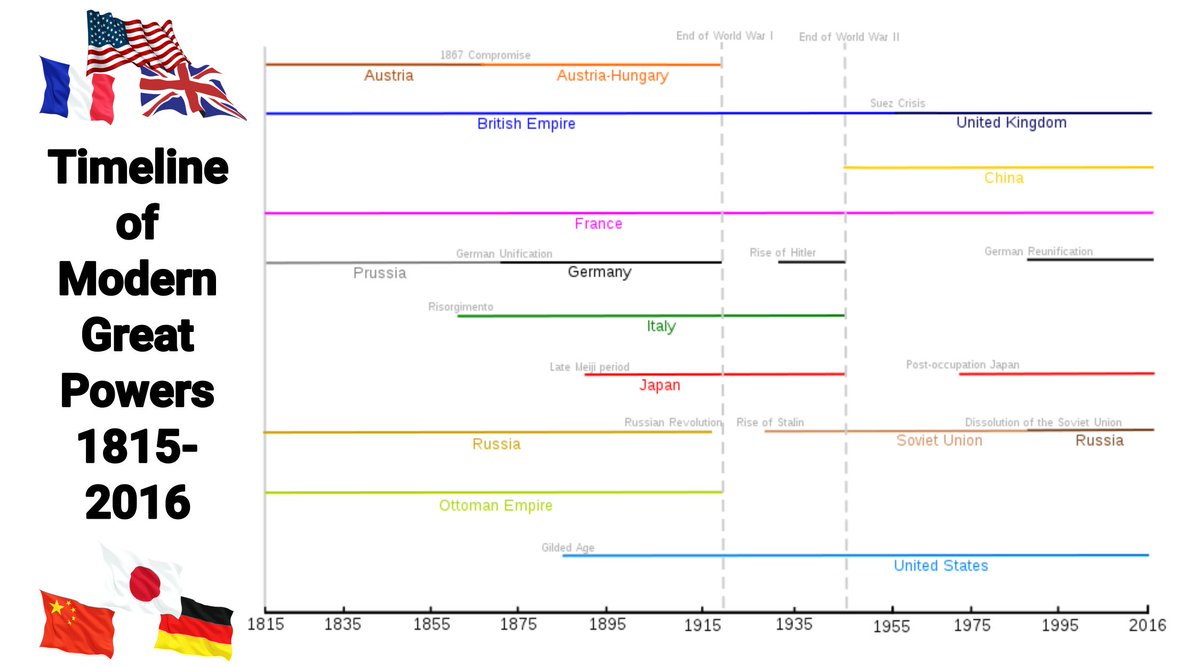

Historically, a time of the GP started in the 18th century when five European strongest states (the United Kingdom, France, Prussia, the Habsburg Monarchy and Russia) were competing against one another. Until the WWI the GP club was exclusively reserved for the European states[13] while after 1918 two non-European states joined this club – the USA and Japan. China became after the Cold War strongly incorporated into the concert of global GP. The existence of a GP system requires that the international system of foreign affairs has to be of a multipolar nature that actually means to be composed at least by three major actors in international politics. A GP state can not be dependent on other state for security issue and it has to be militarily and economically stronger than other countries who are not members of a GP system of states. In fact, a security issue of those other states depends on one or more GP states.

In addition, those other states are also usually depended politically, financially and economically on one or more GP states. The security calculations of a GP state can be threatened only by other GP member state(s) who can challenge it politically and/or militarily. It is generally understood that to play a role of a GP, one state needs a large territory and population followed by well organized army and military system that is not possible without a strong, functional and above all a successful economy.

A historical experience shows clearly that to possess only one out of all necessary GP attributes means that the state cannot maintain its influence on the international arena for some very longer period of time. That is now exactly, for instance, the case of decreasing international influence and domestic power by the USA. Sweden lost its status of a major European power in the 18th century mainly due to its small number of population or Holland in the 17th century primarily due to its smaller territory in comparison to neighboring France followed by English supremacy in oversea trade. Contrary, a state which is possessing all of the necessary factors of GP is in a real position to successfully exercise its own political and other influences on the others for a longer period of time. The process of passing from regional isolation to the status of European GP can be well seen on the example of the Russian Empire in the 18th century. The country was at the beginning of the century isolated and underdeveloped but due to a general progress during the whole century Russia was finally in 1792 by the Jassi Peace Treaty with the Ottoman Sultanate and in 1795 by the Third division of Poland-Lithuania recognized by the other European GP as a member of their club. As a consequence, Russia was in the following period from 1798 to 1815 directly involved in the games of European GP regarding the confrontation of the French Revolution and revolutionary armies of Napoléon Bonaparte.[14]

Nevertheless, as the 18th century was progressing, Russia was becoming gradually more stronger and influential in the international relations due to three crucial factors: a size of the land, its huge population and reach natural resources. All of these factors directly participated to the process of creation of the mighty Russian military land-force which became in 1815 strongest in continental Europe. In this year the Russian army entered Paris by crossing the whole Europe and winning battles from Leipzig (1813) to Waterloo (1815).

Contrary to the Russian case, the United Kingdom at the end of the same century became a global GP mainly due to its powerful navy[15] that was backed by its strong economy which was very much founded on direct exploitation of the British oversea colonies. In the next century, the Brits succeeded to establish an extensive oversea empire and to became a major player in the world politics at the time of Queen Victoria[16] but very much due to their geopolitical position as an „island nation“ whose security and colonial expansion was well protected by a powerful Royal Navy that was practically playing the role of protection wall around the United Kingdom.

Several theories of the Cold War argue, like the so-called “Freezer Theory“ for instance, that during that historical period of time both domestic and international conflicts were the products of the superpower competition in global politics. However, when the competition ended in 1989, the local and/or regional histories absorbed these conflicts where they became left transforming themselves into the territorial disputes, conflicts and open wars between the regional powers for the sake to settle historical accounts. Probably the best examples are the conflict over Nagorno Karabakh, destruction of ex-Yugoslavia, the conflicts over South Ossethia and Abkhazia or the Ukrainian crisis. All of those conflicts from the Adriatic to the Caucasus have been at the same time both the destabilizing factors of and challenge for the European integration and continental security.[17] For the realists, post-Cold War conflicts in a new power context is simply returning back of the international relations to the normal geopolitical reality of global politics as inescapable power policy. International system once again after the Cold War became the GP state system based on the “Westphalian Order“ as the states of the GP bloc are still the key factors and actors in both their own domestic areas and international politics as it was the case from 1648 to 1945.

Zero-Sum Game

The primary organizing principle of IR and global politics once again became after 1989 the “sacrosanct“ principle of a state sovereignty[18] that is only valid for the GP but not for the ordinary states (“small fishes“) like for Serbia in 1999 or Libya in 2011. State-centric model of the international politics that is currently on global politics’ agenda is known in theory as “Billiard Ball Model“ which suggests that states, at least those having a rank of the GP, are as billiard (snooker) balls impermeable and self-contained actors. The model tells that the GP influence each other through external pressure either by diplomacy or direct military action. The survival is the prime concern of any state but struggling for power on global scene is the concern of only those states which are considered to be the GP. The “Billiard Ball Model“ of global politics has two fundamental implications:

- Clear difference between domestic and international politics.

- Conflict and cooperation in global politics is primarily determine by the distribution of economic, political and military power among states.[19]

The crucial characteristics of contemporary GP state are:

- To maintain order and carrying out regulations within its own borders only by itself without interference from outside (ex. Russia and the Chechen rebels in the 1990s) that is a focal feature of a real sovereignty status.[20]

- To promulgate its own policy of interest in international relations by all „allowed“ means that is proving a real GP status in IR.

Therefore, it is in essence unavoidable that the state-system of international policy and relations is operating in a context of anarchy what means that external politics operates as an international “state of nature“.

A basic principle of any GP state is the principle of self-help that means as possible as a reliance on inner resources which are understood as the crucial reason that state prioritize survival and security from the outside world.

Therefore, the establishment and exploitation of all kinds of colonies or/and territorial expansion of the motherland in order to obtain natural resources, labor force, market or better security conditions are seen as quite necessary imperialistic practice. If the GP state is unable to establish its own global, continental or regional hegemony, it seeks to activate a concept of balance of power that is a condition in which no one state has a predominance over others at the same time tending to create general equilibrium and prevent the hegemonic ambitions of other states.

Nevertheless, in the case that IR of the GP work on the background of a self-help principle, the power-seeking inclination of one state is a result of competing tendencies in other state(s). That is exactly how we can explain the reason of the policy of Russia’s economic, military and political inclination on the global level during the presidency of Vladimir Putin as an atavistic reaction to the US unscrupulous and Russophobic policy of a global hyper-hegemony in the 1990s after the dissolution of the USSR and disappearance of the Cold War’s bipolar world.[21] Unfortunately, most often, in such cases of the IR system, conflicts and even direct wars are inevitable between the GP as the examples of both world wars are clearly manifesting.

One of the fundamental rules of the realistic view of global politics and foreign affairs is that any gain, especially territorial, by one state or side is equivalent to the loss by another competition state or enemy bloc. This is the so-called “Zero-Sum Game“ as it is added the winner’s gains and the loser’s losses the total equals zero. That was the case, for instance, with Kosovo independence in 2008 (the US victory and Russia’s loss) related to Crimean reintegration into Russia in 2014 (Russian gain and the US/NATO/EU defeat).

Nevertheless, in a global struggle for power, Realpolitik [22] is an unavoidable instrument for realisation of national goals what means that the use of power, even in the most brutal way, is quite necessary and understandable as it is an optimal mean to accomplish foreign policy’s aims. That was, for instance, clearly expressed in 1999 during the NATO aggression on Serbia and Montenegro (from 24th of March to 10th of June).

Future

All the post-Cold War American imperialistic wars of aggression had the same formal ideological justification which was composed by mixture of elements drawn from the Cold War time (“Communist violations of human rights“) and after that. The cliché was and still is that the US as a leader of a “liberal democratic world“ is fighting against “new Hitlers“ and all other “dictators“ and “butchers“ (from S. Hussein to V. Putin) for the sake to “liberate“ the rest of the world that cannot progress under such monstrous rulers.[23] A regional variations of the US imperialism policy explanations after 1945 are visible as, for instance, in the case of the Latin America (“Wars against Drugs“) or in the case of the Middle East and Arab/Muslim world in general (“War on Terror“).

Such US foreign policy, however, created many ambivalent attitudes towards the American empire by many states, movements, parties or individuals around the world including and existing feelings of embarrassment that other GP have to be essentially dependent on the USA. For instance, many Europeans are convinced that the US cannot any more act in global policy like it was at the time of the Cold War as it has to closely operate with the others. Today, it seems to be unlikely that the US will be able to keep its post-Cold War status of a hyperpower and global policeman. Surely, other GP will became more stronger and influential in IR and global politics primarily China and Russia. It only remains to be seen whether they will co-operate or not in ways that promote or undermine world order.

This article was originally published by The Global Politics where all images were sourced.

Feature image: Source: One World of Nations

Sources

Alan Isaacs et al (eds.), Oxford Dictionary of World History, Oxford−New York: 2001.

Andrew Heywood, Global Politics, London−New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Bear F. Braumoeller, The Great Powers and the International System: Systemic Theory in Empirical Perspective, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Georges Castellan, History of the Balkans From Mohammed the Conqueror to Stalin, New York: Columbia University Press, 1992.

Jeffrey Haynes, Peter Hough, Shahin Malik, Lloyd Pettiford, World Politics, New York: Routledge, 2013.

Joshua S. Goldstein, International Relations, Fifth edition, New York: Longman, 2003.

Martin Griffiths, Terry O’Callaghan, Steven C. Roach, International Relations: The Key Concepts, Second edition, London−New York, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2008.

Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery, Second edition, New York: Humanity Books, 1983.

Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books, 1987.

Richard W. Mansbach, Kirsten L. Taylor, Introduction to Global Politics, Second edition, London−New York: Routledge, 2012.

Stefano Bianchini (ed.), From the Adriatic to the Caucasus. The Dynamics of (De)Stabilization, Ravenna: Longo Editore, 2001.

Steven L. Spiegel et al, World Politics in a New Era, Third edition, Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning, 2004.

Tim Dunne, Milja Kurki, Steve Smith (eds.), International Relations Theories. Discipline and Diversity, Third edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Vladan Dinić, Tito (ni)je TITO: Konačna istina, Beograd: Novmark, 2013.

Zbignew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives, New York: Basic Books, 1997.

Иванка Ћуковић Ковачевић, Историја Енглеске. Кратак преглед, Београд: Научна књига, 1991.

Перо Симић, Звонимир Деспот (уредници), Тито: Строго поверљиво. Архивски документи, Службени гласник: Београд, 2010.

Перо Симић, Тито: Феномен 20. века, Треће допуњено издање, Службени гласник: Београд, 2011.

Славољуб Шушић, Пробни камен за Европу. Војно-политички коментари, Београд: Војна књига, 1999.

Notes

[1] The term superpower was originally coined by William Fox in 1944 for whom such state has to possess great power followed by great mobility of power. At that time, he argued that there were only three superpower states in the world: the USA, the USSR and the UK (the “Big Three”). As such, they fixed the conditions of Nazi Germany’s surrender, took the focal role in the establishing of the UNO and were mostly responsible for the international security immediately after the WWII (Martin Griffiths, Terry O’Callaghan, Steven C. Roach, International Relations: The Key Concepts, Second edition, London−New York, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2008, 305).

[2] China, with its enormous economic and man-power potentials followed by its rising military capability, will soon emerge as the most influential GP in global politics overtaking a role of a sole hyperpower from the USA. The 21st century is already a century of China but not of the USA as it was the 20th century.

[3] Richard W. Mansbach, Kirsten L. Taylor, Introduction to Global Politics, Second edition, London−New York: Routledge, 2012, 577.

[4] Israel is the only exception from this definition as this state has as its “West Bank” the USA. In other words, when we speak about the USA in IR, we speak de facto about Israel and the Zionist loby in the USA.

[5] The European Union (the EU, est. 1992/1993) with its central motor, the French-German axis, became a new GP in global politics. Therefore, the USA is not anymore in a position to dictate and implement global policies like at the time of the Cold War. After the creation of the EU, the US administration seeks a multilateral action with the EU in several hot-spot areas of the conflics in Europe as ex-Yugoslavia or Ukraine.

[6] Today, a formal GP status have the USA, Russia, China, France and Britain and MP status arguably have Canada, Italy, Brasil, Japan, Germany, Argentina, Turkey, India and/or Iran. However, if we consider the USA as a West Bank of Israel then the later is the only hyperpower in the world.

[7] Richard W. Mansbach, Kirsten L. Taylor, Introduction to Global Politics, Second edition, London−New York: Routledge, 2012, 578.

[8] Gross domestic product (GDP) is the total sum of goods and services that is produced by one state in a given year but not including goods and services that are produced abroad by domestic individuals or companies. Gross national product (GNP) is a total value of all goods and services produced by a country in a year, whether within the state’s borders or abroad. Gross national income (GNI) is measuring the market value of goods and services which are produced during a certain time period (usually within one calender year) and provides an estimate of a state’s total agricultural, industrial and commercial output.

[9] Martin Griffiths, Terry O’Callaghan, Steven C. Roach, International Relations: The Key Concepts, Second edition, London−New York, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2008, 134−135; Andrew Heywood, Global Politics, London−New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, 7. On the GP, see more in (Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books, 1987). On the historical role of the GP in international relations, see in (Bear F. Braumoeller, The Great Powers and the International System: Systemic Theory in Empirical Perspective, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

[10] However, their strongest economic status is guaranted by combination of several inter-related factors: 1. Their large population, 2. Rich natural resources, 3. Most advanced technology, and 4. Highly educated labor force (Joshua S. Goldstein, International Relations, Fifth edition, New York: Longman, 2003, 95).

[11] In the Ancient World two the most prominent examples of client-system alliances have been Athens-led Arhe and Sparta-led Peloponnesian Alliance. These two political-military alliances fought the Peloponnesian War from 431 to 404 with the final victory of Sparta with crucial support by Persia (Alan Isaacs et al (eds.), Oxford Dictionary of World History, Oxford−New York: 2001, 486). In the contemporary history two the most prominent formal alliances to dominate the international security scene were the US-led NATO (est. 1949) and the USSR-led Warsaw Pact (est. 1955) during the Cold War. The NATO was a clear expression of the American post-WWII global imperialism when the US had “more than 300.000 troops in Europe, with advanced planes, tanks, and other equipment” (Joshua S. Goldstein, International Relations, Fifth edition, New York: Longman, 2003, 105). Its imperialistic role continued and after the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact in 1991 and the formal, but not essential, end of the Cold War.

[12] Steven L. Spiegel et al, World Politics in a New Era, Third edition, Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning, 2004, 696.

[13] Italy and Germany became the members of the GP system after their unifications in 1861, 1871 respectively.

[14] Georges Castellan, History of the Balkans From Mohammed the Conqueror to Stalin, New York: Columbia University Press, 1992, 213.

[15] On the British navy, see in (Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery, Second edition, New York: Humanity Books, 1983).

[16] Иванка Ћуковић Ковачевић, Историја Енглеске. Кратак преглед, Београд: Научна књига, 1991, 64; Alan Isaacs et al (eds.), Oxford Dictionary of World History, Oxford−New York: 2001, 646−647.

[17] On this issue, see more in (Славољуб Шушић, Пробни камен за Европу. Војно-политички коментари, Београд: Војна књига, 1999; Stefano Bianchini (ed.), From the Adriatic to the Caucasus. The Dynamics of (De)Stabilization, Ravenna: Longo Editore, 2001).

[18] A concept of sovereignty refers to a status of legal autonomy (independence) that is enjoyed by states what means in practice that the government has a sole authority within its borders and enjoys the rights of the membership of the international political community. Therefore, the terms sovereignty, autonomy and independence can be used as the synonyms.

[19] Andrew Heywood, Global Politics, London−New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, 6, 7f, 113, 215.

[20] The Chechen Wars in the 1990s were inspired by the Islamic religious nationalism and separatism by the Chechen extremists and have been the first serious post-Cold War test for Russia to prove or not her status of the GP in the new world order created and dictated by the US. Religius nationalism is a political doctrine in which religion and nationalism have synonymous relationship (Jeffrey Haynes, Peter Hough, Shahin Malik, Lloyd Pettiford, World Politics, New York: Routledge, 2013, 52).

[21] An ideological architect of the post-Cold War US hyper-dominance in global politics was an US extreme Russophobe Zbignew Brzezinski who is of the Jewish origin from Poland (Zbignew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives, New York: Basic Books, 1997). His doctrinal ideology of the US global hyper-dominance became the foundation of “Clinton Doctrine” that is the US foreign policy initiative under the Presidency of Bill Clinton (1993−2001), to promote democracy and human rights by using diplomatic means but in fact military aggressions, bombing (the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1999), “coloured revolutions” (Serbia in October 2000) and all other non-democratic means in order to accomplish the crucial Washington’s political goal – global dominance.

[22] This is a German term that became widespread from the time of the German Chancellor (PM) Otto von Bismarck. The term means in IR studies a cold calculation of state’s national interests regardless on the human or moral aspects of its realization. The term is usually understood as a core essence of Realism theories on global politics based on “ruthlessness” (Jeffrey Haynes, Peter Hough, Shahin Malik, Lloyd Pettiford, World Politics, New York: Routledge, 2013, 713). Realism is a political view which operates with power as the fundamental point of politics claiming, therefore, that the international politics is in essence power politics behind which is a principle of Realpolitik. The advocates of Realism argue that international politics is a struggle for power for the sake to deny other states the capacity to dominate. Subsequently, a balancing of power became a central concept in IR developed by the realists. If there is a single world hegemon, global politics is going to be just a struggle between the GP in seeking both political, military, economic, financial, etc. domination and preventing other states or actors from dominating (Tim Dunne, Milja Kurki, Steve Smith (eds.), International Relations Theories. Discipline and Diversity, Third edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, 59−93).

[23] Such cliché was used during the Cold War, for instance, against the Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser (President of Egypt in 1956−1970) but not against the Yugoslav real dictator and the “Butcher of the Serbs” of the Croat-Slovenian origin, Josip Broz Tito (dictator of Yugoslavia in 1945−1980). The reason for such US policy on J. B. Tito was that he became the US client politician, as many dictators all over the world, after 1948 and therefore was simply “intangible” in home affairs. On J. B. Tito biography, see in (Перо Симић, Звонимир Деспот (уредници), Тито: Строго поверљиво. Архивски документи, Службени гласник: Београд, 2010; Перо Симић, Тито:Феномен 20. века, Треће допуњено издање, Службени гласник: Београд, 2011; Vladan Dinić, Tito (ni)je TITO: Konačna istina, Beograd: Novmark, 2013).