Goldman Sachs, Conflicts of Interest…: The Who, What and Why of the EU Commission’s Ad Hoc Ethical Committee

In a belated response to the mounting tide of critical public and political opinion, the Juncker Commission last week informed the European Ombudsman that it would refer Barroso’s appointment as chairman of Goldman Sachs to its Ad hoc Ethical Committee. But what is the Ad hoc Ethical Committee, who sits on it and what is it likely to say?

What is the Ad hoc Ethical Committee?

The Ad hoc Ethical Committee is an informal body of three appointed members who provide advice to the Commission, particularly on former commissioners’ revolving doors moves, but potentially on all matters relating to the Code of Conduct for Commissioners.

The committee’s remit is extremely limited. It can only advise, but not decide, on revolving door moves, via opinions submitted to the Commission. These opinions are not pro-actively published by the Commission but can be released through access to documents, as was done in this case. Ultimately, it is the commissioners themselves who, during college meetings, are to judge their ex-colleagues and determine whether or not their new roles are compatible with the Code of Conduct and the wider EU treaty.

The committee’s remit is extremely limited. It can only advise, but not decide, on revolving door moves, via opinions submitted to the Commission. These opinions are not pro-actively published by the Commission but can be released through access to documents, as was done in this case. Ultimately, it is the commissioners themselves who, during college meetings, are to judge their ex-colleagues and determine whether or not their new roles are compatible with the Code of Conduct and the wider EU treaty.

Aside from this, the committee is also limited in its activities as it cannot act proactively; it can only look at those matters referred to it by the Commission.

Who sits on the Ad hoc Ethical Committee?

As of July 2016, the members are Mr Christiaan Timmermans, Ms Dagmar Roth-Behrendt and Mr Heinz Zourek.

Of the three, Dagmar Roth-Behrendt is the most well-known. This German social democrat stood down as an MEP in 2014 after five terms in the EU legislature. During her time in office, she sat on the Legal Affairs committee and was rapporteur on, among other dossiers, the 2012 reform of the Staff Regulations (which contain the revolving door rules and other terms of employment for EU institution staff). She is now a special adviser to Commissioner Andriukaitis (Health & Food Safety), focussing on “assessing the situation of executive agencies of DG SANTE”. Roth-Behrendt’s husband is Horst Reichenbach, who has led several Commission departments before heading the Commission’s task force for Greece 2011-15. He is now a director of the European Bank for Reconstruction – and a special adviser to Commissioner Moscovici (Economic and Financial Affairs, Taxation and Customs). Unsurprisingly, Roth-Behrendt and Reichenbach recently made it ontoPolitico’s list of “Brussels’ most notable political power couples”.

Heinz Zourek is another established EU player. He was in the Commission, specifically as director-general at DG for Taxation and the Customs Union until December 2015, after first joining the Commission in 1995. He is also a special adviser on the financial transaction tax to Commissioner Moscovici, and was inadvertently caught up in a 2015 cash-for-access scandal when he refused to meet the influential British politician Jack Straw who sought to lobby EU officials on behalf of paying clients.

Christiaan Timmermans is a former judge at the Court of Justice (2000-2010) and was previously at the Commission’s legal service.

Since members of the Ad hoc Ethical Committee for commissioners’ ethics are appointed by commissioners themselves, the committee’s independence might be considered limited. But this concern is compounded by the fact that the Juncker Commission appointed Roth-Behrendt and Zourek, both of whom had already been appointed by commissioners as their special advisers. Surely such proximity puts them in an awkward and potentially conflicting situation?

Given the heavy criticism levelled at the Commission when it appointed Michel Petite as chairman of its ethics committee back in 2009, it is particularly surprising that the Juncker Commission chose to recruit for its Ad hoc Ethical Committee in a similarly questionable manner. In 2012, then Commission President Barroso decided to re-appoint Michel Petite as Ad hoc Ethical Committee chairman, despite questions of judgement raised about Petite’s own career choices. Petite had had a controversial spin through the revolving door, from heading up the Commission’s legal service, to moving to global law firm Clifford Chance in 2008. Petite lobbied the Commission on behalf of Clifford Chance’s clients, including ones from the tobacco industry. Following an NGO complaintcriticising the re-appointment of a lobbyist as chairman of the ethics committee, the European Ombudsman protested in writing to Barroso and recommended that Petite be replaced. Petite’s ‘resignation’ from the Ad hoc Ethical Committee was announced a few days later.

What is the Ad hoc Ethical Committee likely to say on the Barroso case?

As the committee in its current set-up only ‘took office’ in July 2016, there is no precedent we could use to assess the advice it will provide on revolving door moves. Barroso’s move to Goldman Sachs will be the first time the committee is tasked with assessing a revolving door move. Previous ethics committee have approved almost all new jobs proposed by ex-commissioners, but there have been some notable exceptions.

During the 18-month period between November 2014 and April 2016 which required new roles of Barrosso II commissioners to be authorised by the Juncker Commission, opinions given by the Ad hoc Ethical Committee in its previous constellation led two former commissioners to withdraw a total of three requests for the approval of such new jobs. While the Commission refused to provide any further information on the positions concerned in these withdrawals, former education commissioner Androulla Vassiliou confirmed to CEO that the committee’s opinion had signaled potential conflicts of interest connected to her two proposed roles. She therefore decided to reject the offers and did not proceed to seek Commission authorisation for the roles.

An earlier Ad hoc Ethical Committee also issued a negative opinion in the case of former internal market commissioner Charlie McCreevy who in 2010 and in the wake of the financial crash was keen to take a new role at the NBNK Investments bank. Significant controversy arose over this looming revolving door case, including critical media coverage and NGO complaints. After the Ad hoc Ethical Committee provided its negative opinion and the Commission subsequently threatened to reject the role, McCreevy ultimately withdrew his request for authorisation. Nevertheless, the Commission was happy to authorise McCreevy to take up another controversial role – with prominent European low-cost airline Ryanair.

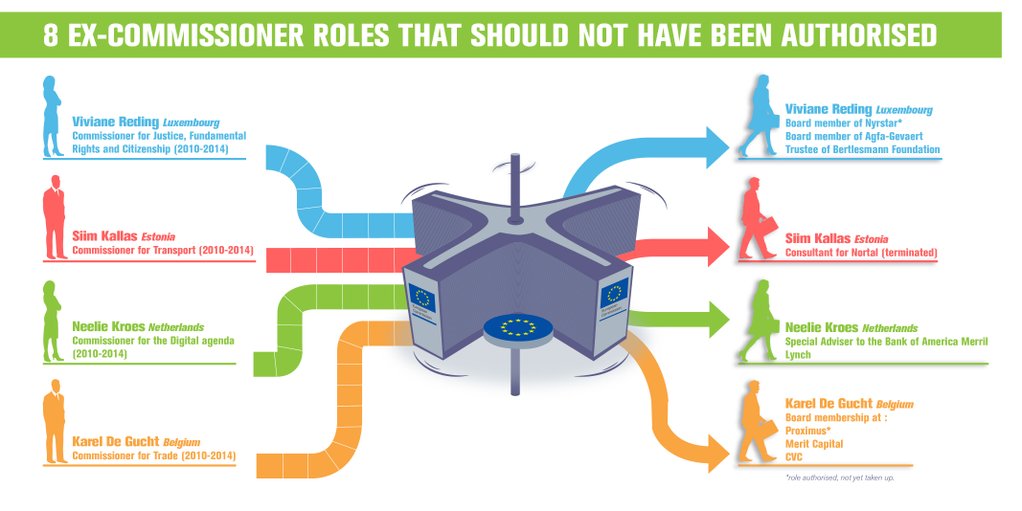

Notwithstanding these examples, CEO’s 2015 report points to several problematic new roles taken up by former commissioners about which both the Ad hoc Ethical Committee and the College of Commissioners failed to be as critical as we would have expected.

The need for professional, independent and truly transparent decision-making

It is clear that the whole decision-making process around departing commissioners’ revolving door moves must be reformed – a reform that must focus on creating a truly independent and transparent ethics committee. Members of the College, who will themselves one day be ex-commissioners, should not be involved in the appointment of committee members whatsoever, nor should they have any part in the decision-making on revolving doors cases.

Instead, we need professional, independent and truly transparent decision-making. As part of wider reform of the Code of Conduct for Commissioners, the Alliance for Lobbying Transparency and Ethics Regulation (ALTER-EU) has advised for the Ad hoc Ethical Committee in its current form to be replaced by a fully independent ethics committee of experts, who have no links to the EU institutions and are recruited from member states’ ethics and administration systems. This fully independent ethics committee should be responsible for the whole authorisation process, supported by a well-resourced secretariat with investigative powers.

The case of former industry commissioner Günter Verheugen drives home the dangers of leaving the College of Commissioners to authorise revolving door. When Verheugen left the Commission in 2010, he failed to inform the institution that he set up a consultancy firm, nor did he seek authorisation for it. Once he restrospectively did, the Ad hoc Ethical Committee did not approveVerheugen’s involvement with the consultancy. The Commission went on to authorise the role regardless, flat out ignoring the committee’s advice.

This illustrates why revolving doors decision-making on commissioners’ new roles should be taken entirely out of the hands of the College – and that will entail a serious revamp of the ethical committee.