Going to Hell and Back: Fighting Our Worst Nightmare

Review of the film Bullets of Justice (2019)

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @crg_globalresearch.

***

Bullets of Justice is a gritty 2019 film made by Valeri Milev and Timur Turisbekov, which takes place in the United States during the Third World War.

Bullets of Justice is a gritty 2019 film made by Valeri Milev and Timur Turisbekov, which takes place in the United States during the Third World War. The whole premise of the film is based on the symbolic reversal of our treatment of animals as food products, and shown in all its horror. Muzzles fatten up humans in cages, kill them upside down in factories and throw corpses on to conveyor belts. Their meat is even tinned and sold (“Human Meat, Always Fresh, Steak from a well fed male”). The idea that humans are somehow ‘special’ and superior to animals is ‘debunked’. In an early scene the Grave-digger unearths a human skull and says to his kids: “See, they don’t go nowhere. They just turn into dirty old bones. God is a human mistake. We die ‘cos of some shit and we die full of shit.”

There is an apocalyptic feeling to the film as humans are dying out and some strange human oddities form a resistance to the Muzzles (a woman with a prominent moustache, a fighter who can stop bullets with his chest, and a female leader who talks as if using a home-made speech synthesizer). However, we get the feeling that their resistance is pointless and the Muzzles are the strongest of the two opposing sets of monstrosities.

The portrayal of human monsters is not new in culture as the depictions of the Golem, Frankenstein’s monster and Zombies makes apparent: representations of humans that cannot really live or reproduce, the symbols of anti-nature. Our anxieties about our position in the natural order of things and our treatment of animals have always been reflected in our beliefs and depictions of ourselves as a higher order and created by an omnipotent being.

However, our relations with animals has always been fraught, as Yuval Noah Harari writes:

“About 15,000 years ago, humans colonised America, wiping out in the process about 75% of its large mammals. Numerous other species disappeared from Africa, from Eurasia and from the myriad islands around their coasts. The archaeological record of country after country tells the same sad story. The tragedy opens with a scene showing a rich and varied population of large animals, without any trace of Homo sapiens. In scene two, humans appear, evidenced by a fossilised bone, a spear point, or perhaps a campfire. Scene three quickly follows, in which men and women occupy centre-stage and most large animals, along with many smaller ones, have gone. Altogether, sapiens drove to extinction about 50% of all the large terrestrial mammals of the planet before they planted the first wheat field, shaped the first metal tool, wrote the first text or struck the first coin.”

The Golden Age

These realities contrast wildly with our mythical story-telling of a Golden Age when humans lived in “primordial peace, harmony, stability, and prosperity. During this age, peace and harmony prevailed in that people did not have to work to feed themselves, for the earth provided food in abundance.” And as Richard Heinberg has stated: Dicaearchus of the late fourth century BCE noted “of these primeval men […] that they took the life of no animal”.[1]

Roman Orpheus mosaic, a very common subject.

He wears a Phrygian cap and is surrounded by the animals charmed by his lyre-playing.

“Not so th’ Golden Age, who fed on fruit,

Nor durst with bloody meals their mouths pollute.

Then birds in airy space might safely move,

And tim’rous hares on heaths securely rove:

Nor needed fish the guileful hooks to fear,

For all was peaceful; and that peace sincere.

Whoever was the wretch, (and curs’d be he

That envy’d first our food’s simplicity!)

Th’ essay of bloody feasts on brutes began,

And after forg’d the sword to murder man.”

As Christianity took hold and changed the reverence for nature to the reverence for a monotheistic god, nature itself became demonised as the heavenly was substituted for the earthly. It is interesting to note the similarities between the Devil (“a pair of horns, four claws and a tail”) and the animal-like god of nature, Pan, “the god of the wild, shepherds and flocks, and connected to fertility and the season of spring. Pan’s goatish image recalls conventional faun-like depictions of Satan.”

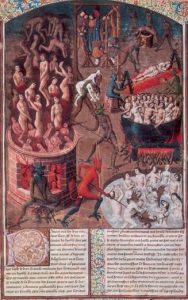

Hell

It seems that deep in our psychology, the more we brutalise animals the more we fear that one day the animals will rise up and brutalise us. However, in some sense it is already happening. As Mike Anderson writes, they do get their revenge but in a slower, but just as deadly, way:

In his article ‘Industrial farming is one of the worst crimes in history’, Yuval Noah Harari wrote:

“The fate of industrially farmed animals is one of the most pressing ethical questions of our time. Tens of billions of sentient beings, each with complex sensations and emotions, live and die on a production line. Animals are the main victims of history, and the treatment of domesticated animals in industrial farms is perhaps the worst crime in history. The march of human progress is strewn with dead animals.”

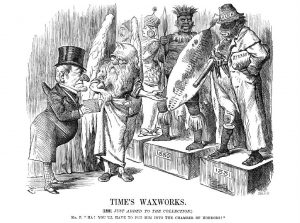

Our attitude towards animals, our bloodthirstiness, has unfortunately carried over into our historical and current treatment of our fellow human beings in the form of colonialism and neo-colonialism. Joseph Conrad expressed it succinctly in his novel Heart of Darkness (1899) where Mr Kurtz (making a report for the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs) reveals his true colonial mentality when he writes ‘Exterminate all the brutes’. The colonial mindset that sees ethnic groups as not much better than animals (brutes) is predicated on the idea that the coloniser is somehow ‘superior’ and ‘civilised’ despite the fact that nowadays and ecology-wise, it is realised that these ‘primitive’ groups generally live in tune with nature rather than destroying it, as the ‘civilised’ West does. Sven Oskar Lindqvist (1932 – 2019) a Swedish author of mostly non-fiction, took Mr Kurtz’s exclamation as the title of his book on the history of colonialism and genocide, Exterminate All the Brutes (1992). The title was subsequently used again for a harrowing four part documentary series (2021) directed and narrated by Raoul Peck who worked with Lindqvist.

“In more recent times, it is fears around what is seen as the neo-Malthusian pathology of deep ecology that prompts a reticence around stressing the animal nature of humans. In this reading of ecology, treating humans as one species among others leads inevitably to the conclusion that the only way to deal with human overpopulation is through the mass elimination of humans. As they would not enjoy higher ontological status than other species, such genocidal practices could be justified by the overall flourishing of species on the planet.”[2]

Once again, our fears of our brutal selves lead us to try and characterise ourselves as more important than ‘mere’ animals in a self-defeating vicious cycle. Which brings us back to the point that Pythagoras made (‘as long as men massacre animals, they will kill each other’). In other words, as long as we treat animals like ‘animals’ (brutes) we will treat each other like ‘animals’ too.

*

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed country by country here.

He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization.