Global Economic Volatility. Towards a New Financial Crisis. Socio-Political Reactions

Read the first part of this series here.

The elements of a new international financial crisis are in place. Although we do not know when it will break out, it is unavoidable, and its impact on world economy will be as significant as the 1880s-90s, 1930s-40s and more recent 2008-09 meltdowns. Worse, far fewer of the global capacities of the latter period – rapid lowering of interest rates, printing of money to buy up state debt (‘Quantitative Easing’), and sufficient fiscal space for bailouts – are available to global crisis managers. And most troubling, many more of the proto-fascistic political characteristics reminiscent of the 1930s are looming, especially in the new contextualisations of the Global South.

The contributing economic factors include:

- sharply increased private debts of corporations;

- speculative bubbles in financial asset prices: stock markets, debt security prices, and in some countries, the real estate sector (at the end of December 2018, a major stock market crash almost broke out in the United States and the contagion effect was immediate, an additional signal that a major crash will have as great a global impact as did 2008-09’s);

- the major banks remain extremely fragile, with share values falling in the United States and Europe since the second half of 2018;

- the US real estate market has become fragile again, overall global prices up by 50% since 2012, with lev- els in excess of those reached just before the crisis that began in 2005-2006;

- Quantitative Easing policies in Europe and their return in the US (as the Federal Reserveeases interest rates in mid-2019 under pressure from President Donald Trump, running for re-election) represent further factors that have the effect of pushing ‘risk on’ funding into South African securities, but at the expense of further rapid outflows when ‘risk off’ sentiments dominate.

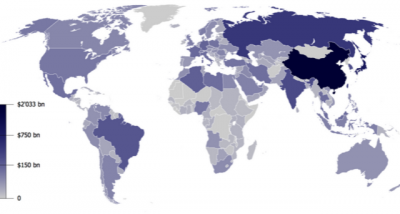

Total Debt (Corporate, Household, Government) in the World Economy, 2012-19

-

Source: Institute of International Finance 2019

Economic growth in the most industrialized “old” countries remains weak. Especially in Europe after low growth in 2017, the year 2018 ended with stagnation and in the case of Germany, a fall in industrial production in the 4th quarter. German authorities lowered their growth forecasts for 2019 to 1% (while in 2016-2017 the annual growth rate exceeded 2%). In the euro zone, growth in the third quarter of 2018 was only 0.2%, the lowest in 4 years. In Japan, growth over the year through period April 2018 – March 2019 was around 0.9%, also down on 2017. The US economy is also in a slowdown phase; the IMF forecasts growth of 2.5% in 2019 compared to 2.9% in 2018. In other words, the North continues to suffer sustained stagnation.

Moreover, Chinese growth is still slowing, as discussed below, as are the economies of the other BRICS, except for India, which is growing at just over 7% annually. Russia is experiencing very weak growth, of the order of 1.2% in 2018 and a forecast of 1.3% for 2019. South Africa was in recession in the first half of 2018, and again in 2019 was likely to fall into a technical recession thanks to -3.2% GDP growth rate in the first quarter. Brazil, which experienced a severe recession in 2015-2016, has regained some growth, but it is very low, at just over 1% in 2018, and out of desperation, the Bolsonaro government authorised a large interest rate cut in mid-2019.

Other so-called emerging countries are also suffering profound economic crises, especially Turkey, Argentina and Venezuela. The symptoms include devaluation of the currency, great difficulties in repaying public and private external debt, and rising joblessness; these are also the kinds of conditions that generate political instability, which all three countries have suffered in different ways in recent years.

To complete the set of gloomy indicators, we will consider the African continent in more detail below, where South Africa’s comparative advantage rests in exporting automobiles, construction and mining services, banking, cellular phones and other consumer goods through Johannesburg-based retail networks (in one case, Massmart, controlled from the US via Walmart). As discussed later, economic conditions are even worse for imports and FDI profit repatriation in Africa than in the rest of the world, as a result of structural exploitation, over-reliance on primary export orientation, and a new debt crisis.

The above remarks relate to the geographical categories within the world community of nations. When we expand our perspective to look at marginalised and oppressed peoples, along the lines of class and other categories, the picture appears even gloomier as a result of neo-fascistic tendencies in many parts of the world. All over the world, economic austerity and political offensives against workers, marginalised and oppressed peoples continue and worsen.

Women are the hardest hit, together with people of colour, indigenous peoples, migrants and young workers. In many instances, women will suffer multiple oppresions if these categorisations are inclusive (for example, young migrant women workers). In the case of all the above groups the offensive is partly a result of the position of these groups in the labour market, for example in historically worse paid jobs. In the case of women and also disabled workers, the impact of the offensive against public services also has a disproportionate impact. Women, who even in times of boom continued to have the major responsibility for caring for children, sick people and elderly people, are adversely affected by cuts in those services, resulting in them often being forced into even more marginal employment or out of the labour market all together. Disabled people who relied on the availability of certain services to work or live independently are similarly impacted.

This offensive operates on different levels:

- repressive policies, including the tightening of immigration rules, attacks on abortion and contraception services, the abuse of indigenous lands for the extraction of extreme fossil fuel or biofuels against the wishes of those communities, etc;

- the emboldening of the extreme right through hate offensives against those groups, including murders in indigenous communities in Brazil by ranchers, official Islamaphobia and anti-semitism, growth of ‘militant’ mobilisations against abortion clinics, increasing violent attacks against LGB and particularly trans people, and mass shootings;

- diminishing support for the most marginalised sections of working people, in part by an aggrieved working class failing to provide solidarity when feminism, anti-racism, LGBTIQ liberation, immigrant rights are labeled as merely ‘identity’ politics, especially when this entails blaming the loss of jobs and services on migrants, women.

Apart from a very minority category of workers whose wages are very high – which makes them prone to allying with big business – almost all categories of waged workers are targeted by economic austerity. These include sectors that had historically succeeded in winning important rights, whether in the industrial sector, in public services, in the financial sector (banking, insurance) and in the commercial sector. Examples include:

- the new precariousness of working conditions and contracts;

- the facilitation of dismissals in part through technological change;

- stagnation or a fall in the purchasing power of wage-workers and popular sectors in general;

- increased retirement ages, with stagnation or fall in pensions;

- decreased access to and quality of public services;

- the reduction in the number of employees protected by collective agreements;

- attacks on the rights of union members and the rights to organise and strike;

- increased indebtedness of working class households all over the world (through consumer loans, mortgage debts, student debts, tax debts, microcredit for survival – and women represent more than 80% of the 120 million people who use such high-priced services worldwide – and rising peasant debts not only in countries like India where the phenomenon has taken on dramatic proportions but also in northern countries.

Source: Branko Milanovic

- precarious work, especially the increase in part-time work by women in services (cleaning, catering, personal care);

- destruction of public services such as public transport, childcare and healthcare, resulting in an increased unpaid workload for mothers; women’s pensions are structurally very low because of the years not worked (because of the need for care for small children at home);

- discriminatory measures in the unemployment system include less income for “non-head of households,” who are mostly women;

- sexual harassment of women in many sectors and in precarious employment (male power in hiring women, which were unveiled in #MeToo);

- decline in access to abortion and contraception rights, in the United States at both local (city) and state levels; closure of family planning centres; non-reimbursement for contraception, lack of sexual education in schools; rise of anti-abortion religious groups in both the US and Latin America with the extreme example of Brazil (Poland and Ireland represent contrary forces given victories in reproductive rights mobilisations);

- the rise of fundamentalism in India, Bangladesh, with more frequent public punishment of “adulterous” women or young women with non-approved sexual contact; but also revolt of young women against the extremely harsh family regime, e. g. Saudi Arabia;

- calls for women to have more children in Turkey, Hungary, Poland, for nationalist reasons;

- the Russian Federation’s Duma, under pressure from the authorities and the Orthodox Church, decriminalized domestic violence in 2017;

- countries where 40% of serious crimes, primarily against women but also against children, occur in the family environment;

- growth of the sex industry worldwide includes sale of women in Libya, slavery of immigrant women, growing pornography in prostitution, amongst other aspects;

- ongoing inequality of women farmers even in small family farms, as Via Campesina regularly reports;

- violence against women, including femicide, domestic violence, harassment of women on the streets;

- in Italy, under pressure from lobbies of very virulent separated fathers, portrayed as as “masculinists”, fundamentalist components of the Catholic Church and a government formed by a coalition between an extreme right-wing party and the Five Stars movement, a project was launched to reform family law to make divorce much more difficult; and

- in Argentina, in August 2018, parliament rejected the bill that legalized abortion.

All of these social processes combine home-based patriarchal power and a wider attack on the rights of women and the LGBTIQ movement by an authoritarian state. Globally, authoritarian forms of government are being strengthened without, so far, taking the form of military dictatorships. In spite of winning electoral contests, the new rightwing leaders are curtailing fundamental democratic freedoms. The means of the repressive forces have greatly increased, which allows for an increased intrusion into the lives of individuals and organisations. The use of preventive arrests is spreading, even in the “old” bourgeois democracies. Legislative and judicial powers are being reduced in many places to the benefit of executive power.

There is, of course, political resistance to all these trends. The various forms of attacks on workers’ rights, women’s rights, the rights of migrants, and on all categories of the oppressed and oppressed fortunately provoke many struggles all over the world. Feminist mobilisations are the most encouraging, but there are many others. Labour struggles are less important than before in a number of countries, but they are progressing in others such as China and Bangladesh. The new forms of organisation or mobilisation that partly respond to the loss of political weight of the organized workers movement are developing and making it possible to build new blocks of the working classes: there are similarities between the mobilisations of the Argentine piqueteros (2001-2003) and those of the Yellow Vests in France (2018-2019), as well as the 2011 movements of the ‘Arab Spring’ and the Occupiers, or the mobilisations in Greece (2011-15), Turkey (2013), Mexico against the increase in gasoline prices (2017), and those of Nicaragua (2018), Haiti (2018-2019), the Moroccan Rif (2018), Puerto Rico (2019), Hong Kong (2019) and many other places, including 18 African countries, as we see below. There are also regular mobilisations among school children in parts of the world; we are witnessing increasing mobilisation on the issue of climate, the environment and common goods.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on CADTM.

Eric Toussaint is a historian and political scientist who completed his Ph.D. at the universities of Paris VIII and Liège, is the spokesperson of the CADTM International, and sits on the Scientific Council of ATTAC France.

Patrick Bond is professor of political economy at the Wits University School of Governance in Johannesburg and co-editor of BRICS: An anti-capitalist critique (published by Haymarket, Pluto, Jacana and Aakar).

Source

Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Policy Paper #1/2 on South Africa’s Special Economic Zones in Global Context September 2019 By Eric Toussaint, Ishmael Lesufi, Lisa Thompson and Patrick Bond

Featured image is from Wikimedia Commons