Getting It Right: Hugo Chávez and the “Arab Spring”

Some opening vignettes might set the right tone for properly appreciating the question of “who was right” about the so-called Arab Spring. (The notion of there having been an “Arab Spring,” a term first coined by U.S. neoconservatives such as Charles Krauthammer back in 2005, is one that has been subject to radically diverse interpretations, from marking in generic terms some sort of struggle for “freedom” and “democracy” [as if there is only one kind of democracy], to views of a covertly directed process of U.S. political intervention, and direct military intervention. Nonetheless, this article is aimed at those who, even now, are still enchanted with the positive aura of the Arab Spring idea.) As usual, my focus will be on Libya.

The Arab Spring: It’s a Good Thing

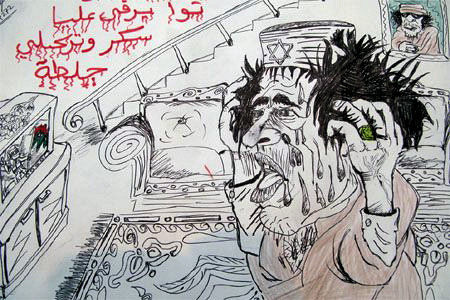

Rejected: Bernard-Henri Lévy. France’s Bernard-Henri Lévy, or BHL, who some claim is a “philosopher,” was one of the loudest and most active proponents of Western military intervention in Libya from the start, and served as a key adviser if not a personal motivator to then French President Nicolas Sarkozy. We “saved Benghazi,” he proclaimed. Guess who is now a persona non grata in the wonderfully new and free Libya that he proudly boasted of aiding in its liberation? Why it’s BHL. He is no longer welcome. Why? For being a Jew. BHL picked a side without even pausing to take note that his “freedom fighters” were painting Benghazi with graffiti depicting Gaddafi as being a Jew (at least in part over some rumour that his grandmother was Jewish), featuring him with the Star of David on his body. Among diplomats, international aid workers, journalists and business travelers, “save Benghazi” has now become “save yourself from Benghazi.” Who got the Arab Spring wrong?

Freedom, Democracy and Human Rights in the “New Libya.” How can we begin to describe Libya after it has been refreshed by the sweet breezes of the Arab Spring, after being liberated by a movement (or whatever) that no decent and right-minded person should ever dare to criticize?

Perhaps we can refer to Libya’s religious freedom, with Egyptian Copts being detained and tortured. This followed gunmen attacking an Egyptian Coptic church in Benghazi. Or we could add some balance here, and talk about the continual attacks against Libya’s Sufi Muslims. There is even more good news, as Libyan women in schools face threats and beatings. It’s not just Libyan women who have won new respect, it is also these female British aid workers who were abducted and raped.

Then there is press freedom, such a central goal for anyone claiming to seek civil liberties and freedom from dictatorship: “a large group of unidentified men stormed the headquarters of Al-Assema TV, a private news channel in Tripoli, and abducted four men, including the owner of the station Jumaa Al-Usta, the former Executive Director Nabil Al-Shibani and journalists Mohammad Al-Houni and Mahmoud Al-Sharkassi.”

In the new Libya, persons displaced by war are fully respected as in the case of “serious and ongoing human rights violations against inhabitants of the town of Tawergha, who are widely viewed as having supported Muammar Gaddafi. The forced displacement of roughly 40,000 people, arbitrary detentions, torture, and killings are widespread, systematic, and sufficiently organized to be crimes against humanity and should be condemned by the United Nations Security Council.” The new Libya has apparently placed racist atrocity in the pantheon of “human rights.” All those who wash their mouths with terms like “genocide prevention” have apparently left the room. With a new Libya come new spelling conventions: the correct way to spell “oppression” is now liberation. What part of this Arab Spring do you support?

“No shame and no gratitude in lawless Libya.” The commentary in the Sunday Mail (2012/3/5) is especially caustic, in ways that were previously reserved for speaking about Gaddafi, but now with some remorse: “The cemetery had remained inviolate through all the long years of enmity between Britain and the Gaddafi regime. But things are different in the new Libya.” Then the paper’s editors proceeded to draw several “uncomfortable conclusions”—again, too late—such as: “Libya after the fall of Gaddafi is a lawless and ungovernable place where horrible actions can be done with impunity by those who have enough guns. The second is that there is no gratitude among many of those we have helped. The third is that those who warned that we did not know–or care enough–who we were aiding have now been vindicated in the most spectacular and gruesome way… our leaders, and our media, should cease to be so simple-mindedly enthusiastic about endorsing every revolutionary movement that appears in the Arab world. Tyrants are bad, but their opponents are not necessarily any better.” Again, who was wrong about the Arab Spring?

Selfless givers of freedom. The people on the “right side of history” (a Eurocentric trope that refuses to go away wherever ignorance is near) have been found to have engaged in humanitarian exploitation, or perhaps if you prefer commercial humanism. It turns out that the Canadian government of Stephen Harper “launched an all-out commercial offensive a full month before the 2011 war in Libya had ended to ensure ‘a return on our engagement and investment,’ newly released documents show.” You may still be undecided about who got the Arab Spring right, but there is no doubt who eyed the Arab “cha-ching!“

With just these few glimpses, one has to ask: how could it possibly be a source of anything other than proud vindication to have been on the “wrong side” of the Arab Spring? But there is a second assertion: that Hugo Chávez was not just on the wrong side of the Arab Spring, but that he also lost support and credibility because of it, and that he is resented for the positions he took.

Chávez “Lost Support” Over the Arab Spring? Arguments Against Evidence

In reply to the last issue, a wide range of news media rushed to take the opportunity of the death of Hugo Chávez to carelessly assert (or insert) that despite any (or many) of his achievements, he will always be remembered as having been wrong about the Arab Spring, thus leaving a bitter taste in the mouths of “many people” in the Middle East. Chávez’s Middle East reputation has thus been irreparably tarnished, resulting in a loss of supporters. Let’s glance at some examples:

Owen Jones, writing in Britain’s The Independent what is otherwise a strong overview of Chávez’s many achievements, adds this criticism:

“And then there is the matter of some of Chavez’s unpleasant foreign associations. Although his closest allies were his fellow democratically elected left-of-centre governments in Latin America – nearly all of whom passionately defended Chavez from foreign criticism – he also supported brutal dictators in Iran, Libya and Syria. It has certainly sullied his reputation.”

Leaving aside the simplistic resort to calling people “brutal dictators,” in the style of George W. Bush and his successor, producing the kind of meaningless pop-polisci marking the flat world depicted by the mainstream media, Jones should have answered a simple question. Chávez sullied his reputation among which crowd? Jones may speak for you, but he does not speak for me, nor does he speak for many others I know. Stating a subjective interpretation of some, as if it were a universal and objective fact, is just sloppy reasoning.

Meanwhile, France24 was completely convinced beyond any doubt that Chávez “ended up tarnishing his reputation in the region when the Arab Spring erupted in 2011,” for supporting Gaddafi and Assad. After all, they have the word of one single source, a political scientist in Paris. Journalism and evidence have apparently been through an extremely ugly divorce–they refuse to just talk to each other in public even as a mere formality.

Danny Postel, Associate Director of the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Denver’s Josef Korbel School of International Studies, complains in Salon that there is not enough honesty in leftist appraisals of Chávez’s record about the way that he coddled “tyrants.” Once more, he takes his own interpretation as the sole one based in objective fact, and indeed, as synonymous with fact. With reference to Libya, try to find where we see proof that Chávez was wrong in backing Gaddafi:

he spoke out emphatically in support of Muammar Qaddafi and Bashar Assad. Chávez had been chummy with the Libyan leader before the 2011 uprising against him: in 2009 he regaled Qaddafi with a replica of Simón Bolívar’s sword and awarded him the same ‘Order of the Liberator’ medal he’d bestowed on Ahmadinejad. “What Símon Bolívar is to the Venezuelan people,” Chávez declared, “Qaddafi is to the Libyan people.” As the Libyan revolt grew and Qaddafi went on a rampage of slaughter, Chávez was one of a handful of world leaders who stood by him: “[W]e do support the government of Libya.”

All we read is that “Gaddafi went on a rampage of slaughter”– as if he was fighting harmless children with their paper airplanes. Once again, absolute silence on the issue of how those fought by Gaddafi were in many cases violent Islamic reactionaries that had many times before engaged in violence against his government, and that in even more cases the anti-Gaddafi opposition targeted and murdered scores of innocent black Libyans and African migrant workers during its so-called democratic uprising.

This supposedly “critical” and “nuanced” left really needs to begin addressing its own racist blind spots, if these writers from Europe and North America expect to ever again be taken seriously in Latin America. Worse yet is when Postel advances as evidence this example of absurd hyperbole, that completely destroys any credibility he might have had–it was meant to be evidence for the thesis that Chávez’s position has been politically costly and embarrassing for his leftwing allies in governments across Latin America…and note that here too not a grain of evidence is presented to support the claim. The reason is simple: the claim is false.

However, it is not just European and North American writers who write similar accusations of Chávez. They might have been easier to ignore had they not been joined by a thin elite of Middle Eastern writers who have added a patina of “Arab legitimacy” to such denunciations.

Thus writing for Al-Monitor, Ali Hashem states at the end of his article:

“Prior to the Arab Spring, it was the pro-West liberalists who did not care for him. After the uprising, however, many of those who had chanted Chavez’s name changed their minds. His support for Gadhafi and Assad after they turned their weaponry on their people divided public opinion about him. Chavez viewed the uprisings as part of an imperialist plan to overthrow anti-American leaders in the region. Arab revolutionists accused him of ignoring the pain of those who had once admired him and invoked his name. To them, he became yet another arrogant leader who chose his interests and the tyrants’ over the people’s.”

“Many.” “Them.” “Divided public opinion.” Until the end of this paragraph, Hashem is simply casting random insinuations without indicating which people, where, and how many (and how he learns of this), really nothing about those who viewed Chávez in these now disapproving terms. Even at the end, all we have is a vague reference to “Arab revolutionists.” Given what these Arab revolutionists have wrought in Libya – which is a very far cry from any socialist, democratic, and independent republic, one has to ask: why should Chávez have even cared about their opinion? Did he ever curry favour with Washington-supported reactionaries and racists who overthrew one of the Arab World’s few secular and socialist governments? One could imagine taking seriously that Chávez offended likeminded supporters–but these were never among them to begin with.

Unsurprisingly, an article by Eman el-Shenawi in the newspaper of the Saudi monarchy, Al Arabiya, wrote with considerable yet unintended irony about Chávez’s support for Gaddafi (reducing analysis to named personalities and not issues). The same author should try writing some critical statements about how his Saudi employers are viewed in Bahrain, where the Saudis and other Gulf states actively and directly participated in the suppression of popular protests…part of an “Arab Spring” the Saudi-funded media pretend had never occurred.

Also unsurprising is that another paper published by a despotic Gulf State, GulfNews and its writer Layelle Saad, can assert that, “Many Arabs lost respect for the Venezuelan leader after he backed despots during Arab uprisings.” Saad, unlike even a pretend journalist, then concludes: “Many Arabs have grown to detest the leader who began to see his double-standards on issues of humanitarian concern. It is doubtful his death will be mourned in the Arab world today.” His double-standards…unlike those of the Gulf Cooperation Council on Bahrain. The “revolution” in Libya was an investment for the Gulf States–Chávez represented a threat to their interests in acquiring control over Libya, and they resent Chávez for that. I doubt their opinions would either surprise or concern Chávez, they were never his friends or allies.

Marking a transition toward more positive appraisals of Chávez in Middle Eastern reporting, Albawaba in “Middle East pines for ‘Arab’ hero Chavez,” drops in a line asserting: “his backing of dictatorial leaders from Muammar Qaddafi of Libya, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and Iran’s regime of Ayatollah saw his popularity dwindling during the Arab Spring.” Yet again, no evidence, no opinion polls or other surveys, nothing except that you take this paper at its word. How does this writer know that Chávez’s popularity was dwindling? It’s a quantitative statement–so quantify it.

In the United Arab Emirates’ The National, Abdelhafid Ezzouitni compiled a digest of opinions in the newspapers of the region. Assuming that it is in any way a representative sample, the repudiation of Chávez’s support for Gaddafi and Assad and any suggestion that he lost the support of public opinion in the Middle East, is actually in the minority. Only one example offers a negative view of Chávez’s support for Gaddafi.

As for losing support among allies, Global Post instead notes that Chávez continued to receive the strong support from those whose support he cultivated, such as the government of Syria. The Daily Star of Lebanon again refers us to those in the region who actually supported Chávez to begin with–which is the logical starting point for any argument that Chávez had lost support among friends:

Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank were united in grief on Thursday over the death of Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez, whose untiring support for their cause saw him make blistering attacks on Israel. The 58-year-old Venezuelan president, who died on Tuesday after a nearly two-year struggle with cancer, was hugely popular with the Palestinians for his outspoken support for their plight. “This is a great loss for us,” president Mahmud Abbas said during a condolence call to the Venezuelan representative’s office in Ramallah.

NBC News reported that in Iran support for Chávez also continued past his death, and past the “Arab Spring.”

When it comes to searching for any actual evidence on which opinions are ideally based, one finds little or nothing to support the claim that Chávez “lost support” in the Middle East for his refusal to jump on the humanitarian interventionist bandwagon, spearheaded by NATO and the U.S. State Department. After all, he cannot have lost any support that he did not have to begin with.

Chávez’s Anti-Imperialist Knowledge

In anthropology, when students are trained in fieldwork methods, and what we read about doing ethnographic field research, special emphasis is placed on key informants: those with advanced and accumulated knowledge of their own culture and who can thus serve as valuable guides for outsiders seeking a deeper understanding of their culture. Typically such key informants would be elders, chiefs, shamans, and so forth.

In the Latin American context, some leaders have acquired advanced and accumulated knowledge of U.S. imperialism, both through time spent in (in)direct confrontation with it, and through personal experience. This is the case of Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua, who in the 1980s led the Sandinista government as it fought off CIA-funded counterrevolutionaries and had to deal with various CIA and other U.S. plots, such as the mining of Nicaragua’s harbors and backing local media and opposition groups. Daniel Ortega leads Nicaragua once again, and stood firmly in support of the government of Muammar Gaddafi. Ortega knows something about how U.S. imperialism works.

Cuba’s Fidel Castro is a survivor, on many levels. Fidel survived over 600 foreign assassination attempts, including some outlandish CIA plots that had they not been confirmed would have made anyone referring to them seem like a mad conspiracy theorist. Cuba was invaded by forces backed by the U.S. under John F. Kennedy, and has endured decades of destabilization attempts. If Fidel is an expert on anything, and he is an expert on a great deal, it is U.S. imperialism and how it works. Both Ortega and Castro denounced intervention in Libya, showed no foolish enchantment with Gaddafi’s opposition, and indicated their support for the government of Libya.

Thus we come to Hugo Chávez too, long demonized by Washington, surviving a coup that was backed by the U.S., and presiding over a Venezuela that saw the U.S. Embassy actively involved in political intervention. As just one example among many, one U.S. Embassy cable detailed its plans (and actual steps taken) in U.S. covert intervention in Venezuela, including these aims: “1) Strengthening Democratic Institutions, 2) Penetrating Chavez’ Political Base, 3) Dividing Chavismo, 4) Protecting Vital US business, and 5) Isolating Chavez internationally.” Some of the key U.S. agencies pursuing these aims were USAID’s Office of Transition Initiatives, and so-called NGOs such as Development Alternatives International (DAI), Freedom House, and CIVICUS. After witnessing what was done in Venezuela, it was only reasonable–and proven to be quite justified–for Chávez to be more than skeptical of “spontaneous” street protests that received the immediate support of Western powers who themselves threaten almost instant military intervention.

Like many other conscious Latin Americans, students of Latin America’s history since independence from Spain, Hugo Chávez was well acquainted with the nearly 200 years of U.S. intervention in the affairs of Latin American states, and is much better positioned to speak on these issues with considerably more expertise than many of his Middle Eastern counterparts, or some North American or European commentators whose main claim to fame is that they have a blog. Unfortunately, when it comes to U.S. imperialism, a great many critical Latin Americans know exactly what they are talking about, as much as Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya may wish to pretend otherwise.

The point is that individuals such as Chávez were well “trained” to recognize patterns, to piece together different bits of information, to critically scrutinize events on the ground in the context of past actions and proclamations, and to place seemingly random events into a coherent picture. In the case of Libya, Chávez was correct that the U.S. sought the first opportunity to intervene militarily, and he rightly opposed that, and was consistent about it from the start. Chavez was correct even when those who ought to have known better asserted that the U.S. was not going to intervene in Libya. Chávez made his principles and objectives very clear from the start and throughout his tours of North Africa and the Middle East: that Venezuela would not stand for the continued intervention of U.S. imperialism, that it would instead stand by those targeted by it, and that it would do what it could to support the Palestinian cause, and that it would seek to build an alternative alliance of nations that stood for long-valued principles of self-determination, non-intervention in state’s internal affairs, and the quest for social and economic justice.

SLOUCHING TOWARDS SIRTE: NATO’S WAR ON LIBYA AND AFRICA

Slouching Towards Sirte:

NATO’s War on Libya and Africa

by Maximilian Forte

- ISBN: 978-1-926824-52-9

- Year: 2012

- Pages: 352 with 27 BW photos, 3 maps

- Publisher: Baraka Books

Price: $24.95

CLICK TO ORDER FROM GLOBAL RESEARCH