George H. Walker Bush: Cold War Ends and New World Orders

The death of certain political figures, notably those of a vast imperium, is bound to provoke less criticism or critical insight than soul searching pursuits. With the US in the mauling clutches of Donald J. Trump, the nightmare that was supposedly never to happen, nostalgia prevails in establishment circles. What ever happened to traditional duplicity and dynasty politicians, with their sanctimonious call upon the good Sky God benefactor and the messianic mission? The US Republic, even as it was being emptied of its worth during their tenure, could at least be assured of predictable corruption. Decay, yes, but on their controlled terms.

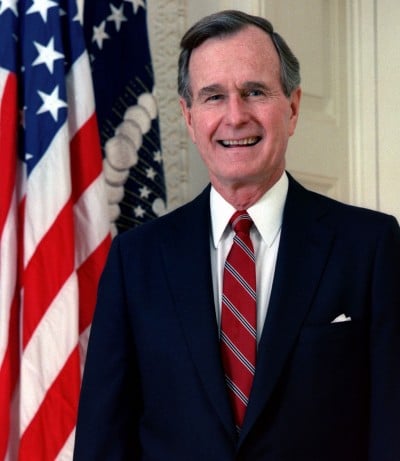

The death of the forty-first president, George H.W. Bush was a fine reminder of that point, a man of standing and missions who could be said, by Time, to be a creature of Aristotle’s “practical wisdom”. A “natural born leader” was he, one “comfortable with dissenting views” and skillful in his employ of “strong advisers”.

The New York Times, with ceremonial hat tilting, saw Bush as “part of a new generation of Republicans” and was “often referred to as the most successful one-term president”. The recipe for this success, according to such commentary, seems to have been written in foreign rather than domestic fields. He is seen as a masterful juggler, “handling” the collapse of the Soviet Union and ensuring “the liberation of Eastern Europe”. As the Cold War curtain was drawn, Bush, reprising his role as a Second World War naval aviator, remained calm.

Bush’s passing is a reminder about a particular moment of history. The Soviet Union packed up in disarray, its own imperium unfolding as based closed and forces left. This left the way, dangerously, for an uncontained hegemon. The United States became Prometheus unbound, even if its power was initially advertised under the broader umbrella of a “New World Order”.

Bush gave an inkling of what this order would look like in his address to a joint session of Congress on September 11, 1990. “The crisis in the Persian Gulf, as grave as it is, also offers a rare opportunity to move toward a historic period of cooperation.”

Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, having invaded Kuwait in August 1990 after reading mixed signals from Washington, had presented an alibi and pretext for principled aggression, done so, artificially, under the blanket of international norms. Bush made the spurious claim that the Iraqi invasion had been prompted “without provocation or warning,” ignoring the July assurance given to Saddam by US ambassador to Iraq, April Glaspie, that Washington had “no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait.” He saw, in Baghdad’s efforts, a stretched historical analogy. “As was the case in the 1930’s, we see in Saddam Hussein an aggressive dictator threatening his neighbours.”

Crucial to this was a condescending hand to the Soviet Union: that it be welcomed “back into the world order”. (Had it been absent for the duration?) Such language was couched in the confidence of an imperial leadership convinced that the barbarians had been subjugated and would, if not exactly lend their support, avoid any effort to sabotage Project USA.

These shaky norms were defended by a coalition, assembled in January 1991, disproportionate in its scope involving two dozen countries, but it lent itself to the dangerous illusion that the US should, and could, become a post-Cold War policeman equipped with discriminatory wisdom and fine acumen. New World Orders, when invoked, tend to be preludes to further conflict. President Woodrow Wilson, vainly obsessed with the League of Nations, did much to aspire to a moral structure that had, within its own foundation, ruination and despoliation. As Europe recoiled in 1919 from self-inflicted slaughter, a second world war was in gestation.

In that very suggestion that a country might be central to remaking a global system came the defective nature of US foreign policy and its messianic, delivering strain: an empire seen in the context of duty and shouldering a heavy burden to make a world safe for something or rather. (Democracy less than money and hustling.) Expelling Saddam from Kuwait was a false advertisement for future collective security, a concept that had been doomed in the aftermath of the First World War.

The 1991 mission also came with an unhealthy sense that the Vietnam syndrome had been purged, rendering US military interventions somehow free of original sin. Morally inspired giants could intervene in foreign conflicts at will without lasting and dangerous consequence. Father Bush thereby begot the failings of Bush Junior in a Middle East repeat in 2003 that continues to shake the region in paroxysms of sectarian rage.

No figure can be considered in splendid isolation. Bush was Ronald Reagan’s vice-president for eight years, much of it featuring a president prone to astrological advice (quite literally) and amnesiac episodes. He also took a leaf out of the latter’s book of deception over the arms-for-hostages deal, professing ignorance about it in 1987. It is one of the few points that his biographer, Jon Meacham, finds fault with him over. Then came the supply side economics that remains a perennial disease of US economics: you coddle and favour the wealthy through sugary tax cuts, increase public debt and slash public funding.

If the beasts of relativity were to be consulted, Bush Sr could be seen as better in value than certain US presidents, but only marginally. He, after all, presided over the motor of hubris that did lead the US into a lengthy sunset even as it hectored the rest of the world. In evaluating his own son’s exploits, he was guarded and concerned about the turn of power after September 11, 2001. He was particularly concerned of the neoconservative hardliners. “I don’t like what he did,” reflected Bush on former Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld, “and think it hurt the president, having his iron-ass view of everything”. In the annals of empire, the two Bushes, separated by a Clinton, remain more consistent than the hair splitters would wish.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research and Asia-Pacific Research. Email: [email protected]