Fukushima: A Journey through an Ongoing Disaster

The Making of “A Body in Fukushima”

“A Body in Fukushima” is an ongoing project that consists of still photographs shot by William Johnston of Eiko Otake performing in the area surrounding the Fukushima Daiichi Reactor and of video interpretations of those still photographs made by Eiko.

Representative images and videos are embedded in the text below.

—

|

A Body in Fukushima Winter 2014, excerpt. Full video here. |

One day in November of 2013 I answered the phone to hear the voice of Eiko Otake saying excitedly, “Bill! What do you think of going to Fukushima to shoot photos of me performing in the stations along the Jōban Line?” For several years Eiko, better known as half of the performance duo Eiko and Koma, and I had collaborated in the classroom and by then knew each other well. We had co‑taught two different courses, Japan and the Atomic Bomb and Mountaintop Removal Coal Mining in which we integrated movement exercises with historical and environmental studies. We both have long-standing interests in those and related topics, and had spoken at length about the triple disaster of 3.11 in Japan. Soon after the earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011, we had talked about our concern for the people of Tōhoku and exchanged feelings of dread at the unfolding nuclear disaster in Fukushima. And I knew that she had visited Fukushima with a friend only five months after 3.11. But this new proposal took me by surprise.

Earlier that year Harry Philbrick, the Director of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, had invited Eiko and Koma to perform in that city’s renowned 30th Street Station. Koma was suffering from an ankle injury however, so Eiko decided to create a solo work, the first of her career.

The grandeur of the Philadelphia Station led Eiko to think afresh about the deserted train stations she had seen along the Jōban Line near Fukushima.

She remembered thinking at the time how some of those stations would never be used again in the foreseeable future. Not long before, they had been busy with schoolchildren, commuters, shoppers, tourists, and travelers. As she watched the businessmen and women in suits and travelers with their suitcases waiting for trains in the halls of the 30th Street Station she thought, “what if I dig a hole into this marble floor as if digging a well for water and that hole goes and reaches to Fukushima: then it is like a hole that is the passage to another world in Alice’s Wonderland.” By dancing in the stations of Fukushima before performing in Philadelphia it seemed possible, as she put it, “to make that distance between two places malleable.” As Eiko later recalled, “I thought about taking some photos of the stations in Fukushima and of dancing in both Fukushima and Philadelphia. In that way, my body would carry a piece of Fukushima for the people in Philadelphia.” The journey had started in what Eiko conceived as a series called “A Body in Stations.”

|

|

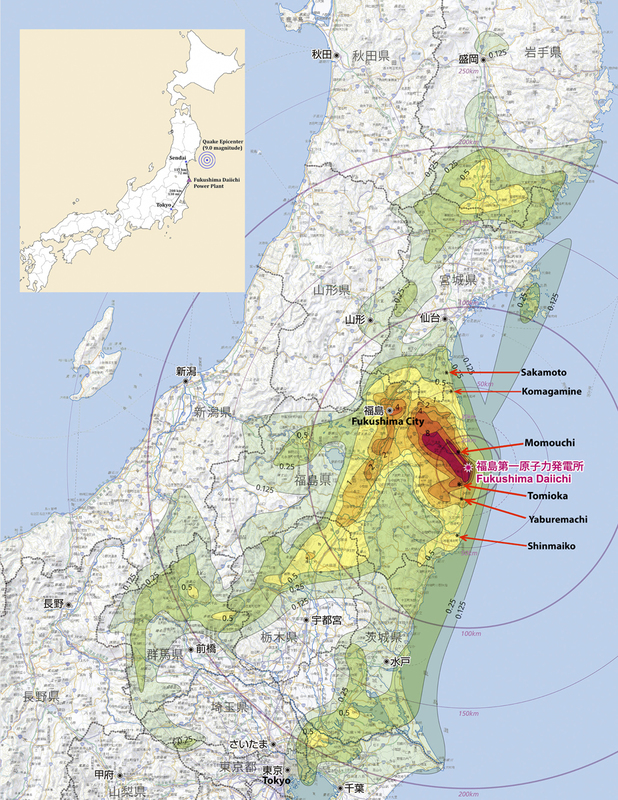

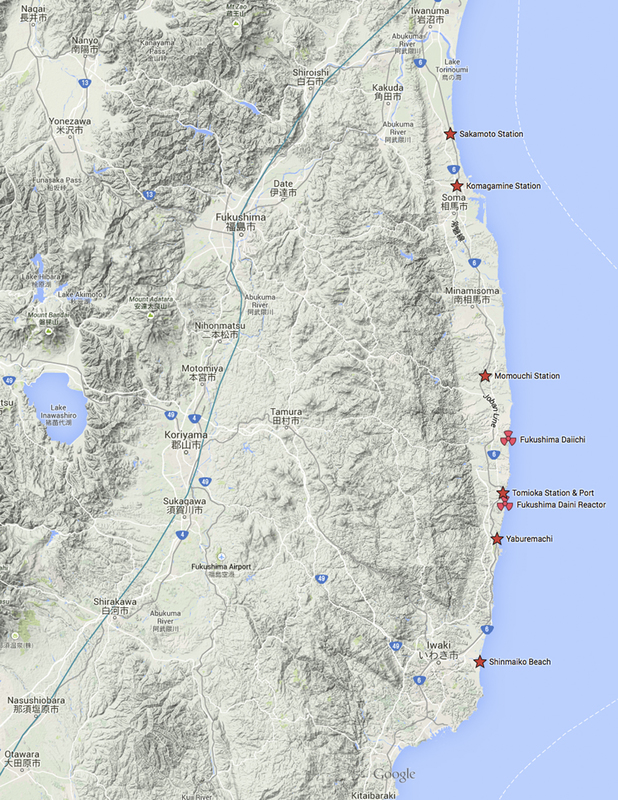

We met in Tokyo on January 14, 2014, and took the train from Ueno to Iwaki, in Fukushima. There, we rented a car and drove first to Hirono, at that time the furthest north one could travel on the Jōban Line, and from there started to explore the stations that had been closed as a result of the 3.11 disasters.

It was late in the afternoon but we decided to explore Kido Station, the first where Eiko was contemplating performing. The station was boarded up, the streets eerily deserted. No damage from the earthquake was immediately visible and the tsunami had not reached that far inland. A cat scampered across in front of a house; a police car drove by us but the officers said nothing. Personal mail, books, and manga fell out of a broken garbage bag on the sidewalk. Kido was close to J-Village, which had been the training ground for Japanese soccer players in 2002 when Japan had co-sponsored the World Cup, and soccer motifs decorated the streetlamps of the deserted streets. In front of the station stood a dosimeter reminding us of the invisible disaster that had spread across Kido and many other towns to the north and west.

|

|

|

|

The next morning we drove around the area closer to the coast east of Kido station. Huge black vinyl bags lined the road on both sides in places, and on the fields further away they were stacked two or three high and sometimes more. We later learned that they were one-ton bags filled with radioactive soil and debris. A half devastated house stood close to the road and I parked the car in its driveway. We got out and walked around the neighborhood. Houses that had been damaged by the earthquake and tsunami stood untouched for nearly three years because of the invisible blanket of radioactive dust that covered them. One house, modest in size, had its front sliding glass doors smashed apart by the tsunami so that the entire front of the house was open to the elements, which was true for almost all of the houses in this neighborhood. From stairwell to the second floor a computerized voice announced the time. I wondered whether batteries could last that long. The only other sounds were of the wind blowing the faded curtains. A stuffed toy duck, now nothing but a bit of radioactive debris, lay on shards of broken glass.

|

Another house had roof damage from the earthquake but suffered little damage from the tsunami. White tarpaulins had been weighted down with sandbags to keep the roof from leaking until it could be repaired.

|

We walked back to the car and explored the house next to the driveway in which we had parked. It was large and built traditionally, with huge, naturally formed beams holding up an intact roof that stood above an interior that looked as though a miniature tornado had swept through it. Household belongings were strewn in complete disarray. Dolls and other objects still sat upon the shelves in front of an upright piano that lay on its back, pinned down by a fallen pillar. In what must have been the living room, two chairs had been placed so that one could sit there and look out at what once must have been a lovely garden. The owners must have returned and sat down for a time; I could only imagine the range of emotions they might have felt.

|

|

The neighboring house across the street had been nearly as large and elegant. Its front also had been hit by the tsunami. A corner pillar was washed away leaving the roof intact, cantilevered by its large beams. A photo lay among the rubble, its glass shattered. But it was possible to make out the image: an aerial view of the neighborhood in better times, perhaps in the 1970s or 1980s, showing a large number of houses clustered together. After returning, I discovered that it had been called Yaburemachi (破町), quite literally “torn town,” perhaps the legacy of tsunamis past.

|

We looked at each other and we both knew that I needed to make some images of Eiko performing there. A broken house was outside the original idea of “A Body in Stations” but the place somehow demanded our attention. It became a turning point for the entire project. While we kept the Jōban Line stations as definite destinations we also watched for other locations that called for attention. There were many. We spent the rest of that day, January 15, 2014, traveling from Kido to Tatsuta and further north to Tomioka. We ended the day with a look at Yonomori Station. Everyplace else we visited allowed short-term visitors, but Yonomori was just across the line of permitted entry. We thought that it was for a good reason and kept our stay short.

|

|

|

|

|

The following day we drove far inland and around the entire zone of radioactivity so that we could visit stations north of the Fukushima Daiichi meltdown site. In the afternoon, we reached Momouchi, the station just north of Namie, which was inside the evacuation zone, or as it is euphemistically called in Japanese, the “zone of difficult return” (帰還困難区域).. It had been only slightly damaged by the earthquake but was well away from the tsunami. By then we had established a rhythm to our work. I suggested places where she might perform. Eiko would reflect on it or suggest another, and after some consideration choose her costumes. When we exhausted the possibilities for one site or when we ourselves got exhausted, we moved to the next. The afternoon light of the short winter days was fading before we finished.

|

|

Our last day was January 17, which was clear and cold. Our first destination was the station at Shinchi. We followed the road to its location on the GPS. I thought there must be a problem with the GPS system, since there was nothing at that site that resembled a station. But it was indeed the right place. Shinchi station had been devastated by the tsunami and since it was well outside the zone affected by radiation it had been completely dismantled. Had it been inside the evacuation zone it would have been left standing, as was Tomioka station. From there we went to the next station to the north, which was Sakamoto. It also had been damaged beyond repair and dismantled, leaving the asphalt covered concrete platform standing above the surrounding fields. In front of the platform a small memorial marked the spot where the station’s front entrance had been. Despite the chilly wind, Eiko performed for an extended period there.

|

|

Our last station was Komagamine, It was still cold if not so windy and Eiko performed for the camera until it was nearly dark.

|

|

As we drove between locations we often were silent. I was deeply moved by the knowledge that many of the people who had lived in the deserted houses and traveled through the now empty railway stations might never return. Even now, four years later, many of those evacuated are living in “temporary” shelters. Some have given up completely on the possibility of return and moved to other parts of the country. Former residents could visit their houses for only a few hours at a time, but because of the radioactivity could not reclaim even undamaged belongings. Outside the evacuation zone much of Tōhoku is on its way to rebuilding. But the nuclear meltdown was a manmade disaster and one that the proponents of nuclear energy promised could never happen. After the fact it was, they claimed, literally beyond conception (sōteigai); a better translation might be that it exceeded their assumptions. But that claim rang hollow. It seemed safe to say that the engineers and corporate executives who designed and ran the nuclear reactors had willfully decided to assume that this kind of disaster was impossible. To plan for it would have dug deeply into corporate profits. Government regulators, by approving the plans for the reactor’s design, accepted that assumption.

In this respect the Fukushima meltdown reflected a larger trend. Where anger and ignorance, expressed through aggressiveness and arrogance, had dominated the first half of the twentieth century, greed and ignorance had come to dominate the second half of the century and continues today. The First and Second World Wars were stirred, in no small part, by real and imagined injustices. Nearly entire populations committed themselves to war efforts, accepting as somehow inevitable the consequences of death and destruction for their own nations but particularly for their victims. Since 1945, while myriad and brutal Asian wars continued, in the wake of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nuclear war has been averted over seven decades. At the same time people came to ignore the insanity of unlimited economic growth and ever-greater wealth. Nuclear energy seems to promise as much electrical power as any economy might need. Its proponents swore to its safety and continue to do so today, despite the many accidents, large and small, that have occurred in nuclear power generation facilities worldwide. Japan’s first major accident occurred in 1978 when Fukushima Daiichi’s No. 3 Reactor was allowed to run out of control for over seven hours. It was successfully brought back under control but the accident was kept secret until 2007. There are many today who support nuclear plants saying that it can cut carbon emissions. Perhaps that is true but nuclear power will never be one-hundred-percent safe especially in a country with frequent earthquakes. Explosions and accidents can produce environmental and human disasters as well illustrated by Fukushima. And there is no avoiding the fact that ignorance of nuclear danger has been cultivated by those who want that danger hidden—recall the cute figure of Plutonium Boy that was created in the 1990s to put the Japanese people at ease with nuclear power.

|

We left Fukushima on January 18, and from there we went directly to visit Hayashi Kyoko, the writer and survivor of the Nagasaki atomic bombing. Eiko and I both were nervous about how she would see the images we had created. Upon seeing a selection of ten images, Ms. Hayashi said, “Because you are in these pictures, I look at each scene much longer. I see more detail. I see each photograph wondering why Eiko is here, how she decided to be here, how she placed herself here.“

When Harry Philbrick saw the images he immediately wanted to exhibit them at PAFA. Eiko showed them to other curators, and soon we had three exhibitions planned for the fall of 2014 and winter of 2015, at the Galleries of Contemporary Art in Colorado Springs and at Wesleyan University.

Not long after Eiko had returned to the United States while I stayed in Japan to research my next project, she contacted me asking if I would like to return to Fukushima in the summer. Despite the scheduling difficulties I knew it was something we had to do.

We returned to many of the same locations we visited in January over the course of five days in late July. Some things had changed but it was all too clear that parts of Fukushima were fated to become nuclear wastelands for the foreseeable future. We worked all day and then assessed the day’s images in the evening. Where we shot fewer than 2,000 images in the winter we shot over twice that number in the summer.

–

|

A Body in Fukushima Summer 2014, excerpt. Full video here. |

In pursuing this project it has been my desire to bring attention to the suffering that nuclear power had imposed on the people of Fukushima in particular, but beyond Fukushima, too. Through witnessing itself we can reflect on and help bring about change to what is being witnessed. For me, Eiko’s performances make visible the anguish of the people and other living beings who have suffered from the Fukushima Daiichi meltdowns and allow us to bear witness with a kind of intimacy that otherwise remains on the margins. Many have forgotten, or want to forget the fact that the disaster is ongoing and will be for a long time to come. Corporate interests and their governmental supporters are invested in making us forget at a time when the Abe administration is committing to putting Japan’s nuclear plants back online. Which makes this a continuing journey. I hope that Eiko and I will be able to go and bear witness again to the true price of nuclear energy.

William Johnston is Professor of History, East Asian Studies, and Science in Society at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut but for the 2015-16 is Edwin O. Reischauer Visiting Professor of Japanese Studies at Harvard. His books include Geisha, Harlot, Strangler, Star: A Woman, Sex, and Morality in Modern Japan. New York, Columbia University Press, 2005 and The Modern Epidemic: A History of Tuberculosis in Japan. Cambridge, Council on East Asian Studies Publications, Harvard University, 1995. He is also the author of “Hōken ryōmin kara rettō no hitobito e: Amino Yoshihiko no rekishi jujutsu no tabiji” (From Feudal Fishing Villagers to an Archipelago’s Peoples: The Historiographical Journey of Amino Yoshihiko), Gendai shisō(revue de la pensé d’aujourd’hui), vol. 41, no. 19, 2014, pp. 232-249.

He is working on a book about the history of cholera in nineteenth-century Japan. His photographic work has been exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia, the Galleries of Contemporary Art at Colorado State University, Colorado Springs, and at Wesleyan University, and has appeared in numerous publications including The New York Times.

Born and raised in Japan, and based in New York since 1976, Eiko Otake is a movement-based multidisciplinary performing artist. For over forty years, she has worked as Eiko & Koma performing worldwide. For the 50 plus works they have co-created, both Eiko and Koma handcrafted sets, costumes, sound, and media. Eiko is currently presenting a solo project, A Body in Places, which opened with A Body in a Station, a twelve hour performance at Philadelphia’s Amtrak station in October 2014. Photo exhibition A Body in Fukushima, a collaboration with photographer William Johnston, tours with the project. A recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, the Samuel H. Scripps American Dance Festival Award, the Dance Magazine Award, and an inaugural USA Fellowship and the Duke Performing Artist Award, Eiko regularly teaches at Wesleyan University and Colorado College.

Recommended citation: William Johnston with Eiko Otake, “The Making of ‘A Body in Fukushima’: A Journey through an Ongoing Disaster,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 9, No. 4, March 9, 2015.