For $10 Billion of “Promises” Haiti Surrenders its Sovereignty

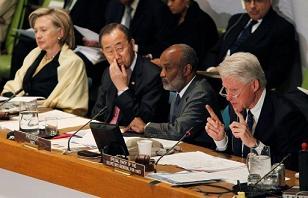

International Donors Conference at the UN

It was fitting that the Mar. 31 “International Donors Conference Towards a New Future for Haiti” was held in the Trusteeship Council at the United Nations headquarters in New York. At the event, Haitian President René Préval in effect turned over the keys to Haiti to a consortium of foreign banks and governments, which will decide how (to use the conference’s principal slogan) to “build back better” the country devastated by the Jan. 12 earthquake.

This “better” Haiti envisions some 25,000 farmers providing Coca-Cola with mangos for a new Odwalla brand drink, 100,000 workers assembling clothing and electronics for the U.S. market in sweatshops under HOPE II legislation, and thousands more finding jobs as guides, waiters, cleaners and drivers when Haiti becomes a new tourist destination.

“Haiti could be the first all-wireless nation in the Caribbean,” gushed UN Special Envoy to Haiti Bill Clinton, who along with US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, led the day-long meeting of over 150 nations and international institutions. Clinton got the idea for a “wireless nation,” not surprisingly, from Brad Horwitz, the CEO of Trilogy, the parent company of Voilà, Haiti’s second largest cell-phone network.

Although a U.S. businessman, Horwitz was, fittingly, one of the two representatives who spoke for Haiti’s private sector at the Donors Conference. “Urgent measures to rebuild Haiti are only sustainable if they become the foundation for an expanded and vibrant private sector,” Horwitz told the conference.”We need you to view the private sector as your partner.to understand how public funds can be leveraged by private dollars.”

“Of course, what’s good for business is good for the country,” quipped one journalist listening to the speech.

The other private sector spokesman was Reginald Boulos, the president of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Haiti (CHIC), who fiercely opposed last year’s union and student-led campaign to raise Haiti’s minimum wage to $5 a day, convincing Préval to keep it at $3 a day. He also was a key supporter of both the 1991 and 2004 coups d’état against former Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, now exiled in South Africa.

In counterpoint, the only voice Aristide’s popular base had at the conference was in the street outside the UN, where about 50 Haitians picketed from noon to 6 p.m. in Ralph Bunche park to call for an end to the UN and US military occupation of Haiti, now over six years old, and to protest the Haitian people’s exclusion from reconstruction deliberations. (New York’s December 12th Movement also had a picket at Dag Hammarskjold Plaza on 47th Street).

“No to neocolonialism,” read a sign held up by Jocelyn Gay, a member of the Committee to Support the Haitian People’s Struggle (KAKOLA), which organized the picket with the Lavalas Family’s New York Chapter and the International Support Haiti Network(ISHN). “No to Economic Exploitation Disguised as Reform. MINUSTAH [UN Mission to Stabilize Haiti], Out of Haiti! “

The exclusion of Haiti’s popular sector was masked by the inclusion of other “sectors” in the Donors Conference, although their presentations were purely for show, with no bearing on the plans which had already been drawn up. Joseph Baptiste, chairman and founder of the National Organization for the Advancement of Haitians (NOAH), and Marie Fleur, a Massachusetts state representative, spoke on behalf of the “Haitian Diaspora Forum.” Moise Charles Pierre, Chairman of the Haitian National Federation of Mayors and Montreal Mayor Gerald Tremblay spoke on behalf of the “Local Government Conference.” Non-governmental organizations had three spokespeople: Sam Worthington for the North American ones, Benedict Hermelin for the European ones, and Colette Lespinasse of GARR, for the Haitian ones. Even the “MINUSTAH Conference” had two speakers.

Michele Montas, the widow of slain radio journalist Jean Dominique and former spokeswoman for Ban Ki-Moon, spoke in English and French on behalf of the “Voices of the Voiceless Forum” which held focus group discussions with peasants, workers and small merchants in Haiti during March. “A clear majority of focus group participants,” she said, “from both rural and urban areas, strongly believe that there is a critical need to invest in people. Focus groups highlighted five key immediate priorities: housing, new earthquake resistant shelters for displaced people; education, in all of the school systems throughout the country; health, the building of primary healthcare facilities and hospitals; local public services, potable water, sanitation, electricity; communications infrastructure, primarily roads to allow food production to reach the cities… There seemed to be unanimity on the need to invest in human capital through education, including higher education.”

“Support for agricultural production,” Montas continued, “was stressed as a top priority… Agriculture, perhaps more than other sectors, is seen as essential to the country’s health, and the prevailing sentiment is that the peasantry has been neglected.”

Even Préval has recognized this neglect, but he got in trouble last month when he called on Washington to “stop sending food aid” because of its deleterious effects on the Haitian peasant economy (see Haïti Liberté, Vol. 3, No. 36, 3/24/2010). The U.S. responded that there was “severe corruption” in his government.

Préval fell back into line. His government prepared a Post-Disaster Needs Assessment report (PDNA), the conference’s reference document, with “members of the International Community.” Of the $12.2 billion total it requested for the next three years, only $41 million, or 0.3 percent, would be earmarked for “Agriculture and fishing.”

The centerpieces of the Clinton plan are assembly factories and tourism (see Haïti Liberté, Vol. 3, No. 36, 3/24/2010). But the former president still pays lip-service to agriculture.

In the hallway outside the Trusteeship Council, Haïti Liberté asked Bill Clinton what had led him last month before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to renounce his policies as US president of dumping cheap rice on Haiti.

“Oh, I just think that, you know, there’s a movement all around the world now,” Clinton responded. “I first saw Bob Zoellick, the head of the World Bank, say the same thing, where he said…, starting in 1981, the wealthy agricultural producing countries genuinely believed that they and the emerging agricultural powers in Brazil and Argentina… that they really believed for twenty years that if you moved agricultural production there and then facilitated its introduction into poorer places, you would free those places to get aid to skip agricultural development and go straight into an industrial era. And it’s failed everywhere it’s been tried. And you just can’t take the food chain out of production. And it also undermines a lot of the culture, the fabric of life, the sense of self-determination… And we made this devil’s bargain on rice. And it wasn’t the right thing to do. We should have continued to work to help them be self-sufficient in agriculture. And that’s a lot of what we’re doing now. We’re thinking about how can we get the coffee production up, how can we get … the mango production up, … the avocados, and lots of other things.”

In other words, the U.S. and other “agricultural powers” would provide Haiti food, “freeing up”Haitian farmers to go work in U.S.-owned sweatshops, thereby ushering in “an industrial era,” as if the cinder-block shells of assembly plants represent organic industrialization.

Now Clinton, sensitive to the demands of Montas’s “focus groups,” promotes agriculture, but as a way to integrate Haiti into the global capitalist economy. Many peasant and anti-neoliberal groups see agricultural self-sufficiency as a way to disconnect and insulate Haiti from predatory capitalist powers.

At a 5:30 p.m. closing press conference, Ban Ki-moon announced pledges of $5.3 billion in reconstruction aid for the next 18 months, exceeding the Haitian government’s request of $3.9 billion. The total pledges amount to $9.9 billion for the next 3 years “plus” – a significant detail given how notoriously neglected UN aid promises are. Bill Clinton announced that only 30% of his previous fund-raising pledge drive for Haiti had been honored.

Haitian Prime Minister Jean Max Bellerive and President Préval played only supporting roles at the Conference, requesting support at the start and thanking nations at the end.

The essence of this conference was summed up by Hillary Clinton. “The leaders of Haiti must take responsibility for their country’s reconstruction,” she said as Washington pledged $1.15 billion for Haiti’s long-term reconstruction. “And we in the global community must also do things differently. It will be tempting to fall back on old habits – to work around the government rather than to work with them as partners, or to fund a scattered array of well-meaning projects rather than making the deeper, long-term investments that Haiti needs now.”

So now, supposedly, NGOs will take a back seat to the Haitian government, but a Haitian government which is working with the NGOs and under the complete supervision of foreign “donors.” Under the Plan, the World Bank distributes the reconstruction funds to projects it deems worthy. An Interim Commission for the Reconstruction of Haiti, composed of 13 foreigners and 7 Haitians, approves the disbursements. Then another group of foreigners supervises the Haitian government’s implementation of the project.

The only direct support the Haitian government got at the Donors Conference was $350 million to pay state salaries, only 6.6% of the initial $5.3 billion pledged. This came after the International Monetary Fund warned that the budgetary support was necessary to keep the Haitian government from printing money, thereby risking inflation.

“We trust that the numerous promises heard will be converted into action, that Haiti’s independence and sovereignty will be respected and ennobled, that the government of President René Préval and Prime Minister Jean Max Bellerive will be facilitated to exercise all its faculties, and that it will be able to benefit, not the white and foreign companies, but the Haitian people, especially the poorest,” said Cuba’s Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez Parilla at the conference. “Generosity and political will is needed. Also needed is the unity of that country instead of its division into market shares and dubious charitable projects.”

Indeed, there are some interesting ideas in the Haitian government’s Action Plan, also presented at the conference. It calls for 400,000 people to be employed, half by the government and half by “international and national stakeholders,” to restore irrigation systems and farm tracks, to develop watersheds (reforestation, setting up pastureland, correcting ravines in peri-urban areas, fruit trees), to maintain roads, and to work on “minor community-based infrastructure (tracks, paths, footbridges, shops and community centers, small reservoirs and feed pipes, etc.) and urban infrastructure (roadway paving, squares, drainage network cleaning) … and do projects related to the cleaning and recycling of materials created by the collapse of buildings in the areas most affected by the earth-quake.”

All that sounds nice, but unfortunately, now the decision is up to the strategists at the World Bank.