Football, Refugee Rights and Hakeem al-Araibi

“Al-Araibi’s case has become a crucial test of world football’s commitment to human rights.” So observed the director of the Castan Centre for Human Rights at Monash University, Sarah Joseph, in a piece last month. “Is this commitment real, or is it a public relations statement tossed aside when the going gets tough?”

Joseph was inadvertently noting the institutional response to human rights: convenient garnish for the conscience show when needed; disposable and mere trifle in more expeditious, political circumstances. All states will, when the dictates of interest claim to apply, be brutally indifferent. For the Australian footballer (soccer player, for some), Hakeem al-Araibi has become a talismanic sword burnished against regimes. But he is also the untidy illustration of hypocrisy amongst governments the world over, a figure to be exploited for moral fanfare. In the Australian case, there is an unmistakable sense that his protection visa mattered less than his enthusiasm for sport.

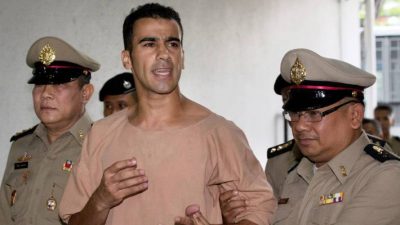

In 2012, al-Araibi was said to be one among several athletes nabbed by authorities in Bahrain in what were termed pro-democracy protests. Two years later, two things happened: the footballer made a dash for it, and received a conviction in absentia for vandalising a police station, notwithstanding that he was, at the time of the said incident, engaged in a televised football match. He subsequently found refuge in Australia in 2017 and began playing semi-professional football for the Melbourne-based Pascoe Vale Football Club.

In November 2018, al-Araibi ventured, with his wife, to honeymoon in Thailand. There, he faced the wonderful world of the Interpol Red Notice, one issued by Bahrain. Interpol has its own guidelines about how to “support member countries in preventing criminals from abusing refugee status while also providing adequate and effective safeguards to protect the rights of refugees” in accordance with the Refugee Convention.

On this occasion, it was clear that the balance had, oddly enough, gone Bahrain’s way: the Thai authorities would consider requesting the footballer. This, despite Interpol’s own injunction that red notices “and diffusions against refugees” would not be permitted where the status of a refugee or asylum seeker was confirmed; that the request was made “by the country where the individual fears prosecution” and that the granting of the refugee status was “not based on political grounds vis-à-vis the requesting country.”

The problem facing al-Araibi was that any return to Bahrain could well land him in more than a deal of strife. That regime has confirmed its credentials as a consistently brutal suppressor of dissidents actual and perceived. Al-Araibi pleaded via an interview with The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald at the Klong Klem Remand Prison in Bangkok:

“Please Australia, keep fighting for me. I pay taxes, I play football, I love Australia. Please don’t let them send me back to Bahrain.”

The Thai government was then reminded by a host of activists and, in a vein of rich hypocrisy, Australian officials, about the following words writ in in United Nations Refugee Convention of 1951:

“No State Party shall expel, return [refouler] or extradite a person to another State where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture.”

In Joseph’s words, if Thailand was to “refouler” al-Araibi, it would be returning him “to the state from which he fled persecution, a grave breach of human rights.” Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison is said to have intervened in a note to Thailand’s Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha claiming a personal interest in the matter and (hear the rustling of ballot papers being counted) the Australian people.

This move stands awkwardly with that of Australia’s own initiatives, through the Interpol National Central Bureau, in informing Thai counterparts that al-Araibi was the subject an Interpol Red Notice. The Department of Home Affairs proceeded to play a poker-faced Pontius Pilate: “any action taken in response to the Interpol Red Notice is a matter for the Thai authorities.” Suddenly, it became clear that certain “obligations” had to be observed (Canberra is more than happy to skirt over refugee matters when needed); besides, the system of an Interpol Red Notice “was not put in place by Australia”.

On Monday, the Thai attorney-general’s office made it clear that it would not pursue the extradition case against al-Araibi, making him free to return to Australia. Various Australian figures expressed unvarnished relief. Humanitarian clubs toasted the news. Much of the noise stirred up in the campaign for al-Araibi came from former Socceroo Craig Foster.

“Speaking to all the people involved, who have worked so hard over this time to try and save his life, it’s an incredible feeling.”

Foster was effusive, perhaps naively so, for “the wonderful people of Thailand for your support and to the Thai Govt for upholding international law.” The battle for the footballer had been “a fight for the soul of sport”. Australian commentators rallied around the bus of goodness, the self-congratulation easing through with saccharine flavours. “Australia is a better place because of you,” tweeted academic and veteran Aboriginal activist Marcia Langton. Australians could be proud about the decision of officials from another country, even if its own government has demonstrated a marked tendency to return individuals to areas of high risk and harm.

This discomforting fact in Australia’s response is made all the more unpalatable by the excitement occasioned by the involvement of that dag for all seasons, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison. It was Morrison who, with his then leader, Tony Abbott, facilitated the systematic removal of a number of Sinhalese and Tamil individuals to the Sri Lankan authorities in 2014 – at sea. There had been “enhanced” screening, a contradiction in terms. Adjusting from a ruinous, vengeful civil war, Sri Lanka was deemed a safe venue for return. The blood had dried; Australian memories, shortened.

Those who bothered to keep an eye on matters had to come to the conclusion that Australian officials were taking a leaf out of the book of police regimes in Latin America: people had, quite literally, been “disappeared”. (Morrison was the highest civilian functionary behind Operation Sovereign Borders, which quite literally militarised the campaign against asylum seekers and refugees arriving by naval vessels.) The response from the Prime Minister Abbott might well have been written by a Bahraini security wallah: “Sometimes in difficult circumstances difficult things happen.”

As the prize winning Iranian journalist Behrouz Boochani, still being detained by authorities sponsored by Australian tax payers, suggested, broader public opinion stirring the protection of human rights does count yet remains fickle, inconstant and somewhat arbitrary. Australians did raise their voices regarding al-Araibi’s plight, but were selective. “I wish public opinion would challenge the gov [sic] just as strongly on the human crisis in Manu and Nauru.” Perhaps becoming semi-professional footballers might help.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research and Asia-Pacific Research. Email: [email protected]