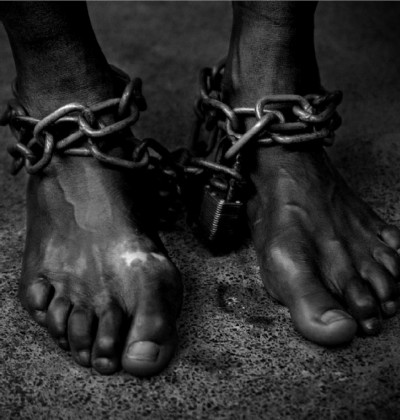

Food for Thought: How Corporations in Thailand Use Slavery to Bring You the Seafood in Your Fridge and on Your Tables

In a large, windowless hall smelling of antiseptic and the sea, hundreds of white-clad men and women in masks line rows of metal tables.

To the tune of Thai pop songs blasting in the background, they make deft work of trays of cooked skipjack tuna, stripping skin and bones in a matter of minutes.

The resulting hunks of brown flesh are stuffed into 6kg bags, ready to be shipped more than 6,000km away to Israel.

This is the factory of Thai Union Group, the world’s largest canned tuna producer, which of late has been acquiring so many big-name seafood firms that it became embroiled in an anti-trust probe in the United States.

Thai Union owns brands such as Chicken of the Sea, John West, King Oscar and Petit Navire. It also supplies processed seafood to other companies.

Its products can be found in major pet food brands as well as supermarket chains such as Sainsbury’s, Tesco, Woolworths and Safeway.

On Dec 4, it scrapped its plan to acquire US-based Bumble Bee Seafoods after the authorities there deemed the deal harmful to local competition.

With an eye on hitting its US$8 billion (S$11 billion) revenue target by 2020, it announced, just two weeks later, plans to buy a majority stake in Rugen Fisch, a leading German canned seafood firm.

With operations so big, the company has been the target of investigations over the use of coerced labour long alleged in the complex supply chains that make up Thailand’s seafood industry.

The kingdom is the world’s third largest exporter of seafood, selling about US$3.17 billion worth of fish products last year, according to statistics from the Thai Frozen Foods Association.

The trail of fish from sea to plate often involves low-wage boat hands from Cambodia and Myanmar and vulnerable migrant workers who process the seafood for suppliers of big exporters.

On Dec 10, just days before the release of an Associated Press report that exposed slave-like conditions on the premises of one of its suppliers of peeled shrimp, Thai Union announced that it would, from Jan 1, directly employ shrimp peelers so as to guarantee their welfare.

Nestle, one of its clients, admitted last month that seafood made with forced labour had found its way into its products.

In a recent interview with The Straits Times, Thai Union president and chief executive Thiraphong Chansiri said he welcomed the scrutiny. “Frankly, I don’t mind,” he said. “We accept the challenge. We accept that it’s our responsibility and we want to do the right thing.”

But he also said the firm became aware of the problem of coerced labour in seafood supply chains only recently.

“Frankly, before 2013, how could we know? First of all, we don’t buy much from the boats in Thailand.

“And then we buy fish delivered to the factory,” he said. “People talked about traceability not long ago.”

Just 4 per cent – or 14,000 tonnes – of the company’s seafood is sourced from Thailand.

But that may mean little in the face of growing calls for consumer boycotts of Thai seafood in Western countries.

The kingdom’s entire seafood export industry has been under threat since the EU issued a “yellow flag” in April for Thailand’s lax controls over illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing.

Since then, the military government has been scrambling to register fishing vessels, legislate the use of ecologically sensitive fishing equipment and weed out the use of forced labour on boats to avert the import ban should the EU follow up with a “red card”.

Thailand exported about US$700 million worth of seafood exports to the European Union last year.

“Certainly we are all concerned,” said Mr Thiraphong.

Technically, a ban would apply only to products sourced from Thailand, but “you don’t know” how each EU country might interpret the ruling, he said.

Thai Union has cut ties with some 2,000 boats over the past two years to ensure ethical labour practices.

Meanwhile, the Thai government last Monday refuted the AP report on rogue shrimp peeling sheds, arguing that it was unrepresentative of the entire industry.

“Don’t just base your judgment on one news article; that is not fair,” Vice-Admiral Chumpol Lumpiganon, a spokesman for the Command Centre for Combating Illegal Fishing, told The Straits Times.

“Anyone who finds a rogue factory can come to us and we will deal with it instantly.”

About 8,000 fishing vessels have lost their licences since the government began cleaning up the industry, leaving about 40,000 now subjected to tighter monitoring.

In a related move, new measures gazetted last month have put seafood factories that violate labour laws at risk of closure.

But migrant worker advocates fear that the application of the rules may remain lax in the domestic seafood market, where consumer pressure for traceable supply chains is not so strong.

“Conditions in the domestic seafood market are always worse than those for the export market,” said Mr Andy Hall, an international affairs adviser to Thailand’s Migrant Workers Rights Network.

Mr Thiraphong said Thai Union, as a market leader, has been “working closely with the Thai government” to support industry-wide reform.

Despite its global ambitions – and the flurry of recent reports about labour abuses in the Thai seafood industry – the company does not intend to loosen its association with its home country.

In September, the company, formerly known as Thai Union Frozen Products, chose to retain reference to the kingdom in a rebranding exercise. “We are very proud to be Thai,” said Mr Thiraphong.

“We chose the name with ‘Thai’ (in it) so that we can represent Thailand in the global landscape.”