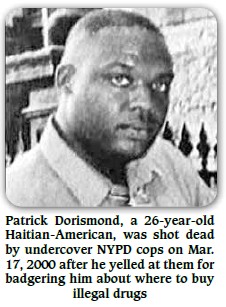

Fifteen Years Ago, the Killing and Funeral of Haitian-American Patrick Dorismond, Shot by Undercover NYPD Cops

The Day Flatbush Exploded

Mar. 16, 2000 was a day like any other for Patrick Dorismond. He worked his shift as a security guard at the 34th Street Partnership in Manhattan and went to have a beer with a coworker after work at the Wakamba Cocktail Lounge. He was in a good mood because the next day was payday.

As Patrick left the bar after midnight, some middle-aged men approached him trying to score some marijuana. Patrick politely told them he didn’t do drugs and asked them to keep it moving. They insisted that surely he knew where they could score. The situation escalated until Patrick’s voice rose, warning the troublemakers to get lost.

The men were undercover NYPD officers instructed to “bring in the dope-peddling good-for-nothings.” Patrick, a 26-year-old Haitian-American whose parents had immigrated to Brooklyn, fit the cops’ profile of a “good-for-nothing,” and they planned to fulfill their quota. Without identifying themselves, the cops attacked the security guard. When Patrick defended himself , two other back-up officers – called “ghosts” – intervened, shooting him in the chest, killing him instantly.

That night, Patrick did not go home to his fiancée Karen and their one-year-old daughter Destiny.

That night, Patrick did not go home to his fiancée Karen and their one-year-old daughter Destiny.

To the naïve, the shooting was a terrible isolated tragedy. But the Black community knew this was police “business as usual,” endured by Black people for decades.

Mayor Rudolph Giuliani attacked the victim, claiming Dorismond was at fault and “no altar boy,” never once expressing regret for the loss of an innocent life. Interestingly enough, Patrick had attended the same Brooklyn Catholic school – Immaculate Heart of Mary – as the mayor, an irony Giuliani chose to ignore.

As the funeral approached, tension was high between a community outraged by police abuse and a police department drunk with arrogance and racism.

Would We Patrol Your Funerals?

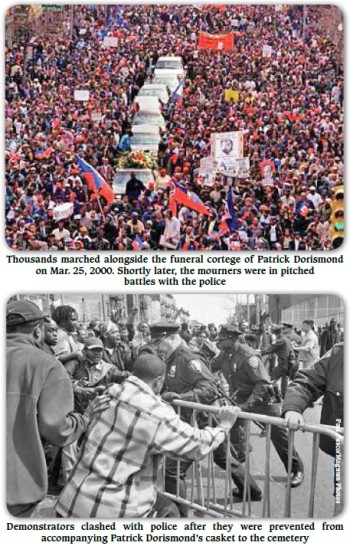

Thousands converged in Brooklyn two weekends after Patrick’s murder to stand with his family and express their repudiation of the latest police slaying. The somber funeral procession on Sat., Mar. 25, 2000 grew in size and anger as it slowly rolled up Flatbush Avenue, a central artery of the Haitian community. By the time the march reached Holy Cross Church where the funeral was held, an ocean of humanity filled Church Avenue. The police were clearly alarmed at the size of the crowd. The air was heavy with grief and anger. Young and old alike looked into the police officers’ faces as if to say: “Why are you even here? This is not your family’s affair. Go back to where you came from, and let us grieve. Would we patrol your funerals?”

It was clear that Flatbush was on the brink of combustion. The spark that ignited the crowd came in the form of yet another police miscalculation. Dorismond’s body was taken out of the church’s back door and loaded into a hearse, which started toward the cemetery for burial. The crowd of thousands wanted to quietly and respectfully follow the casket, but the police stopped them. A melee ensued as the furious crowd demanded to accompany Patrick to his final resting place. One, two, or three confrontations soon mushroomed into hundreds. Rocks and bottles flew. The police lost control of the situation, and found themselves surrounded by and drowning in a sea of fury. White-shirted police captains barked into their walkie talkies, chaos enveloping them.

The terrain had shifted under the feet of the invaders. The indigenous army grew emboldened. The ranks of the enraged swelled with fresh recruits, who streamed in from surrounding streets. Police reinforcements also arrived, chasing the mourners turned demonstrators, but they were in hostile territory. Every doorway was an entrance to a hallway that became an escape tunnel. When the cops tried to close in on prey, a door magically opened, snatching the children from their would-be wardens.

The terrain had shifted under the feet of the invaders. The indigenous army grew emboldened. The ranks of the enraged swelled with fresh recruits, who streamed in from surrounding streets. Police reinforcements also arrived, chasing the mourners turned demonstrators, but they were in hostile territory. Every doorway was an entrance to a hallway that became an escape tunnel. When the cops tried to close in on prey, a door magically opened, snatching the children from their would-be wardens.

Two armies engaged each other on a battlefield called Church Avenue. One was motivated to collect their paychecks and appease their superiors. The other sought to undo and transform years of humiliation into a united fightback. A 15-year-old boy – born in Port-au-Prince but reared in Brooklyn – would later claim that Haitians were born with rocks in their back pockets precisely for these moments of self-defense.

Next, the police cavalry was deployed. In unison, the multitude burst into a chant: “Get those animals off those horses!”

A young man-child ran straight at the approaching enemy lines, did an about face, dropped his drawers, and mooned the cops to the applause and cheers of the mighty crowd. The move struck a chord with the generation of youth warriors. As if rehearsed, the cadre of teenagers saluted their oncoming foes with this perfectly-timed gesture of contempt, signalling a fresh rain of glass, steel, and stone on the police. The horses were turned back. Some mounted cops fell, reduced to a state of atomized desperation.

This was the closest some would ever get to emancipation. Powerlessness dislodged power. Regardless of the aftermath, for that brief moment, oppressed people controlled the situation, their environment, their humanity. Every demonstrator’s smile posed the question: How does it feel, boys, to try to wade into the mighty current of the people’s wrath? Those accustomed to swaggering with full confidence now retreated in full sprints, thinking of their own families and loved ones. Were there human feelings beneath those uniforms and badges?

An NBC news crew wanted to be the first major television network to break the story. The camera crew piled out of the news truck intent upon recording the situation and interviewing the balaclava-clad rebels. They immediately came under fire from a group of young generals who bombarded the news truck with bottles and rocks. Sprinting in high-heals and Dockers, the once-confident news-crew raced back to their van and then sped off with shattered windows and windshield. The masses burst into laughter waving “Bon voyage,” as if to say surely you can misreport from a safe distance, up in your helicopters and your air-conditioned newsrooms. It is not safe for you down here in the street where history unfolds.

Time and again, youths threw bricks and bottles from alleys and rooftops. Time and again, phalanxes of police turned and ran. The underdog was winning.

How many years of accumulated rage detonated that day? The ancestors of the Haitians outside Holy Cross Church that day had risen up against slavery and colonialism and defeated Napoleon’s legions, the mightiest army in that time. Now their Haitian descendants, the daughters and sons of Dessalines, Capois La Mort, and Toussaint L’Ouverture, showed us how to stand up to those who think they are invincible. They showed all of Brooklyn and the oppressed around the world that we all have a Haiti within, searching for redemption.

Resistance to Injustice is Justified

The masses bid farewell to Patrick Dorismond with valiant resistance, assuring that he had not died in vain and promising Guilianni to rache manyòk li – uproot him from office. Dorismond’s murder – coming on the heals of the August 1997 torture of Abner Louima and the February 1999 murder of Amadou Diallo – and the police force’s heavy-hand at his funeral were two drops which made the cup of people’s anger overflow. The police had a taste of the fear of violence their victims live with day in and day out.

“Our best organizers in the South,” the reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. once said, “are the police themselves.” Giuliani’s NYPD proved this once again in March 2000.

Some might tell us not to glorify violent resistance and to limit ourselves to hand-wringing when faced with police abuse and aggression, so often lethal. But nothing has ever stopped oppressors in their tracks like organized self-defense, which is sometimes spontaneous. We should not rule out non-violence and civil disobedience. All are viable and valid tactics in the pursuit of freedom.

In the words of Guyanese freedom-fighter Walter Rodney: “the revolution will be as peaceful as possible and as violent as necessary.” Only the victimized and oppressed can determine which weapon is correct at each confrontation with their brutalizers. Those on the sidelines – comfortable with sermonizing – should stay right there as the people take center stage in standing up against injustice, just as they did 15 years ago.

Danny Shaw is an adjunct professor at CUNY’s John Jay College and a member of the Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL).