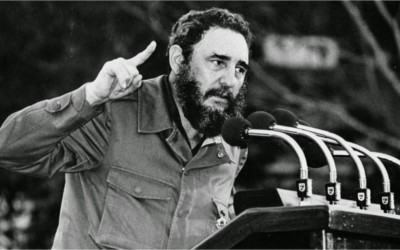

Fidel Castro, Two Years Later: “Morality and Science are not Separated”

Fidel Castro died two years ago this week-end. If US Liberals read Fidel Castro, they’d know Trump is uninteresting. They’d know “nicely sweetened but rotten” ideas cause great suffering in the US. It doesn’t take much to see in Fidel a distinct (in these times) vision: in fact, an ancient one.

But you have to think it’s worth looking for. And there’s the rub. You won’t think it’s worth looking for if you don’t think anything else is possible than what you’ve always expected, philosophically.

Philosophy is not a luxury. Your daily thinking depends upon it. Philosophical conceptions – what it means to be human, for instance – guide everyday choices. This is well-known in analytic philosophy of science. They might have learned it from Marx.

Even those who like Cuba don’t read Fidel. They take students and show them Cuba’s “culture”. But they ignore the ideas. There’s an irony: Accusing Cuba of dogmatism, academics disregard Cuba’s philosophical foundations. If they don’t ask, it’s because they don’t think there’s anything to know.

They assume there are no such foundations. They are “open” while declaring by behaviour that no dissent to their (liberal philosophical) worldview is possible. It is a damaging form of dogmatism, unacknowledged.

When I first went to Cuba, I saw, written on a wall, a statement attributed to Fidel: Al valor no le faltara la inteligencia, a la inteligencia no le faltara el valor. I realized then that this society, this Revolution, expressed a departure from philosophical liberalism: the ideology dominating the North, including Marxists, Aristotelians, anarchists, queer theorists and feminists.

Put simply, Fidel’s statement means you can’t be intelligent and bad, and if you manage to be good, that is, if you manage to actually act out of good will for others, and not just appear to do so, you must also be smart because you’ve properly understood causal interdependence.

Morality and science are not separated.

European philosophers separated the intellectual from the moral. They invented the “fact/value” distinction. They denied facts (or knowledge) about value. There is no truth in the field of value, just “myths and fictions”.

You can flourish intellectually living however you want. You can talk about global justice and ethics, living your passions. No one will note the contradiction.

How you live is one thing, how you think is another. This view dominates still. Cuban philosopher Ernesto Limia says the ineffectiveness of the international left is explained by it. He may be right.

Fidel’s view is more sensible and in fact more common, if one looks outside Europe and North America for ideas. It says that how you live and how you think are interconnected. If I want to flourish intellectually, I should serve others. I should increase my felt awareness of causal interdependence.

It’s radical but only due to damage done by European liberalism.

Knowing reality (science), we know how to live well as human beings (morality): When we know science, we know about cause and effect. We know causal interdependence: laws of nature. If I know the laws of nature, I know my self-interest requires the well-being of others. It’s simple: When I act out of good will for others, I benefit. When I do harm, I am the first to suffer. Cause and effect. Science.

It’s an ancient view. Cuba has demonstrated its commitment. If its history of internationalism (well-documented) were known. Bolsonaro’s current lies about Cuban doctors would have no effect. [i] But there, again, is the rub. We don’t believe what we don’t expect. Cuba’s internationalism is known. But it is not believed because it is not consistent with the liberal worldview that denies its justification.

Cuba’s internationalism is long-standing, and its explanation is clear: Cause and effect, interdependence, laws of nature. Fidel expresses it in almost everything he said and wrote.

Cuba’s role in Angola is an example. UK historian Richard Gott describes the costly mission as “entirely without selfish motivation”. Cuba sent 300,000 volunteers, more than 2,000 of whom died, to defeat apartheid South Africa. In Pretoria, a “wall of names” commemorates those who died in the struggle against apartheid. Many Cuban names are inscribed there. No other foreign country is represented.[ii]

The US claimed Cuba was acting as a Soviet proxy but according to US intelligence, Castro had “no intention of subordinating himself to Soviet discipline and direction.” Former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger wrote in his memoire 25 years later that Castro was “probably the most genuinely revolutionary leader then in power”.

He was revolutionary in his thinking, which continues to influence. Bolsonaro says Cuba’s remarkable doctor program is a way for Cuba to enrich itself. It is not surprising that he says it. It is surprising some believe it.

But it is not any more surprising than those who look South for everything except ideas. Fidel Castro said in 1999, in Caracus, after the election of Hugo Chávez:

“They discovered smart bombs but we discovered something more powerful: the idea that people think and feel”.

It shouldn’t be a radical view, and it is not in many traditions, going back millennia. But to see how that is so, there needs to be at least a little bit of doubt about liberal dogmatism. It would be a step forward just to admit that it exists, and that it’s been effectively challenged. Fidel Castro is one place to start.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Notes

[i] http://www.cubadebate.cu/especiales/2018/11/20/perdon-a-mis-ninos-por-no-haberles-dicho-adios/#.W_at4uhKiM8; http://www.cubadebate.cu/especiales/2018/11/20/minsap-cuba-no-hace-politica-con-la-salud-de-ningun-pueblo-video/#.W_auH-hKiM8

[ii] References are here: https://www.counterpunch.org/2015/07/27/thawing-relations-cubas-deeper-more-challenging-significance/