“Fear Has Large Eyes”: The Sergei Skripal Affair

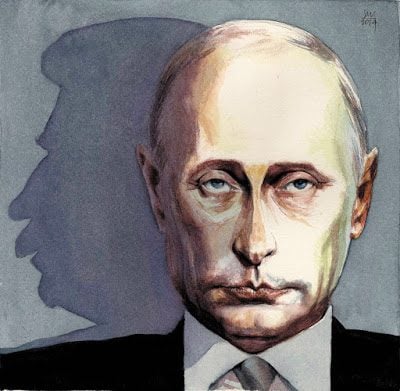

Featured image: Vladimir Putin Painting by Siegfried Woldhek (2014)

“We did not reject our past. We said honestly: ‘The history of the Lubyanka in the twentieth century is our history…’ – Nikolai Patrushev, director of the FSB, Excerpt from an interview in Komsomolskaia Pravda, December 20, 2000.

Historically, the secret services of Russia have garnered an enduring reputation for ruthlessness.

Whether dealing with internal opponents (Think: Ivan The Terrible’s Oprichnina, the Tsarist Okhrana, Felix Dzerzhinsky’s Cheka and the NKVD terror orchestrated by the likes of Genrikh Yagoda, Nikolai Yezhov and Lavrenti Beria) or the external apparatus (Think: Viktor Abakumov’s SMERSH, the role of the KGB in smashing anti-Soviet movements in Hungary and Czechoslovakia, as well as the exploits of the GRU, Soviet military intelligence), the apparatus’ of espionage and counter-espionage have set unenviable standards in uncompromising brutality.

The extraordinarily repressive capacities of the gulag system was of course immortalised by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago and the Lubyanka has become synonymous with Bolshevik terror replete with a signature style of execution every bit as emblematic as revolutionary France’s guillotine: a bullet to the back of the head.

Yezhov’s name provided the label for the most brutal part of Stalinist terror in the 1930s, the Yezhovshchina. That term was the invention of a scared, scarred and cowed populace. But the protagonists of terror have not shirked from either publicly extolling the merits of the wielding of terror or in revealing the ruthless objectives of particular institutions created to promote the security of the state.

Thus it was Dzerzhinsky who declared during the early Bolshevik era that “we stand for organised terror”. And it was Stalin who coined the phrase Smert Shpionam, “Death to Spies”, from which the name SMERSH, a conglomerate of counter-espionage organisations within the Red Army, was derived.

And death has often been the lot of Russian and Soviet traitors: Major Pyotr Popov in 1960, Colonel Oleg Penkovsky in 1963 and Major-General Dmitri Polyakov in 1988 were officers of the GRU who were executed as agents acting in the service of foreign powers.

In Penkhovsky’s case, the legend persists that he was bound to a stretcher and incinerated while alive in a crematorium as a warning to potential traitors. All the evidence points to him having been shot, but the tale of his presumed fate is indicative of the perception of many in the West of a Russian predisposition to cruelty and even barbarity in dispensing ‘justice’ to those perceived as enemies of the state.

“Fear has large eyes” warns an old Russian proverb, and to many in the West, this is as true today as it was in Joseph Stalin’s time. Apart from presiding over numerous purges and the entrenchment of a repressive, totalitarian order, Stalin, who was Georgian, is claimed to have been influenced by Caucasian notions of honour and vengeance in the pursuit of his former rival Leon Trotsky. Not only was Trotsky assassinated by an agent of the NKVD in 1940, his family was destroyed by assassinations and persecutions inflicted by the Soviet state.

Some now seek to paint contemporary Russia with a similar brush. Under Vladimir Putin, who is often posited as a practitioner of the Russian brand of oriental despotism, they point to the deaths of dissenting journalists, political opponents and dissident former members of Russia’s security services. A case was made against two former FSB officials, Andrei Lugovoi and Dmitry Kovtun for responsibility in the death of Alexander Litvinenko, a former colleague of the FSB who died from polonium poisoning in 2007.

Now, the same allegation is being made in regard to the suspected poisoning of Sergei Skripal, a former colonel in Russian military intelligence. Skirpal had been convicted of revealing the identities of Russia’s secret agents to MI6, Britain’s foreign intelligence service. In 2010, he was released into British hands as part of a ‘spy swap’ in Vienna.

At the time, Putin was quoted as declaring that

“traitors always end badly. Secret services live by their own laws and these laws are very well known to anyone who works for a secret service.”

But those who consider this a self-incriminating statement need to bear the following in mind. Skripal, who was officially pardoned by Russia’s then-President Dmitry Medvedev, did not suffer the fate of those who committed similar acts during the Soviet era. In fact, many would argue that he got off lightly with a thirteen-year sentence.

It begs the question: why would Russia attempt to kill Skripal at this time?

While many Western observers will pooh-pooh Andrei Lugovoi’s assertion that Skripal’s targeting is “another provocation by British intelligence agencies” aimed at demonising Russia, others will be more circumspect and reserve judgement because such a campaign of demonisation has been orchestrated in the West and promoted by the mainstream media for over a decade.

Further, the notion that Britain’s intelligence services cannot themselves be involved in the dark arts of murder and ‘black operations’ is simply not tenable. From the so-called ‘Lockhart Plot’ against Vladimir Lenin engineered by M1-1C the precursor to MI6 to complicity in the murder of Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba and a plan to assassinate Irish Taoiseach, Charles Haughey, Britain’s intelligence services have been involved in homicidal conspiracies. Yet, the official narrative continues to uphold the pretence of an almost benign intelligence apparatus averse to plots involving assassinations.

While the aforementioned remarks of Nikolai Patrushev have been taken as evidence by Western analysts that the Russian intelligence service continues to embrace a draconian ethos, it is also worth recalling his comments about British intelligence which he insisted in 2008 has since the times of Queen Elizabeth I, “operated on the principle that the end justifies the means.”

There may be more to this episode than meets the eye.

*

This article was originally published on Adeyinka Makinde’s blog.

Adeyinka Makinde is a writer based in London, England.