The Failure of Imperial College Lockdown Modeling Is Far Worse than We Knew

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

***

A fascinating exchange played out in the UK’s House of Lords on June 2, 2020. Neil Ferguson, the physicist at Imperial College London who created the main epidemiology model behind the lockdowns, faced his first serious questioning about the predictive performance of his work.

Ferguson predicted catastrophic death tolls back on March 16, 2020 unless governments around the world adopted his preferred suite of nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to ward off the pandemic. Most countries followed his advice, particularly after the United Kingdom and United States governments explicitly invoked his report as a justification for lockdowns.

Ferguson’s team at Imperial would soon claim credit for saving millions of lives through these policies – a figure they arrived at through a ludicrously unscientific exercise where they purported to validate their model by using its own hypothetical projections as a counterfactual of what would happen without lockdowns. But the June hearing in Parliament drew attention to another real-world test of the Imperial team’s modeling, this one based on actual evidence.

As Europe descended into the first round of its now year-long experiment with shelter-in-place restrictions, Sweden famously shirked the strategy recommended by Ferguson. In doing so, they also created the conditions of a natural experiment to see how their coronavirus numbers performed against the epidemiology models. Although Ferguson originally limited his scope to the US and UK, a team of researchers at Uppsala University in Sweden borrowed his model and adapted it to their country with similarly catastrophic projections. If Sweden did not lock down by mid-April, the Uppsala team projected, the country would soon experience 96,000 coronavirus deaths.

I was one of the first people to call attention to the Uppsala adaptation of Ferguson’s model back on April 30, 2020. Even at that early date, the model showed clear signs of faltering. Although Sweden was hit hard by the virus, its death toll stood at only a few thousand at a point where the adaptation from Ferguson’s model already expected tens of thousands. At the one year mark, Sweden had a little over 13,000 fatalities from Covid-19 – a serious toll, but smaller on a per-capita basis than many European lockdown states and a far cry from the 96,000 deaths projected by the Uppsala adaptation.

The implication for Ferguson’s work remains clear: the primary model used to justify lockdowns failed its first real-world test.

In the House of Lords hearing from last year, Conservative member Viscount Ridley grilled Ferguson over the Swedish adaptation of his model: “Uppsala University took the Imperial College model – or one of them – and adapted it to Sweden and forecasted deaths in Sweden of over 90,000 by the end of May if there was no lockdown and 40,000 if a full lockdown was inforced.” With such extreme disparities between the projections and reality, how could the Imperial team continue to guide policy through their modeling?

Ferguson snapped back, disavowing any connection to the Swedish results: “First of all, they did not use our model. They developed a model of their own. We had no role in parameterising it. Generally, the key aspect of modelling is how well you parameterise it against the available data. But to be absolutely clear they did not use our model, they didn’t adapt our model.”

The Imperial College modeler offered no evidence that the Uppsala team had erred in their application of his approach. The since-published version from the Uppsala team makes it absolutely clear that they constructed the Swedish adaptation directly from Imperial’s UK model. “We used an individual agent-based model based on the framework published by Ferguson and coworkers that we have reimplemented” for Sweden, the authors explain. They also acknowledged that their modeled projections far exceeded observed outcomes, although they attribute the differences somewhat questionably to voluntary behavioral changes rather than a fault in the model design.

Ferguson’s team has nonetheless aggressively attempted to dissociate itself from the Uppsala adaptation of their work. After the UK Spectator called attention to the Swedish results last spring, Imperial College tweeted out that “Professor Ferguson and the Imperial COVID-19 response team never estimated 40,000 or 100,000 Swedish deaths. Imperial’s work is being conflated with that of an entirely separate group of researchers.” It’s a deflection that Ferguson and his defenders have repeated many times since.

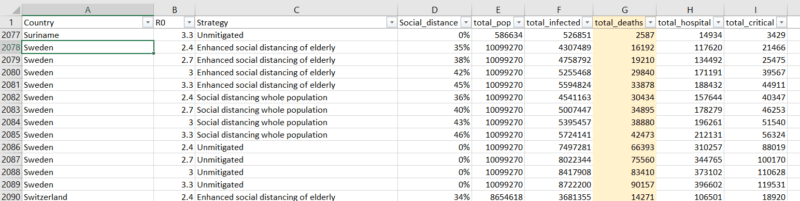

As it turns out though, Ferguson and the Imperial College team were being less than truthful in their attempts to dissociate themselves from Sweden’s observed outcomes. In the weeks following the release of their well-known US and UK projections, Ferguson and his team did in fact produce a trimmed-down version of their own modeling exercise for the rest of the world, including Sweden. They did not widely publicize the country-level projections, but the full list may be found buried in a Microsoft Excel appendix file to Imperial College’s Report #12, released on March 26, 2020.

Imperial’s own projected results for Sweden are nearly identical to the Uppsala adaptation of their UK model. Ferguson’s team forecast up to 90,157 deaths under “unmitigated” spread (compared to Uppsala’s 96,000). Under the “population-level social distancing” scenario meant to approximate NPI mitigation measures such as lockdowns, the Imperial modelers predicted Sweden would incur up to 42,473 deaths (compared to 40,000 from the Uppsala adaptation).

The Imperial team did not specify the exact timing of when they expected Sweden to reach the peak of its outbreak. We may reasonably infer it though from their earlier US and UK model, which anticipated the “peak in mortality (daily deaths) to occur after approximately 3 months” following the initial outbreak. That would place Sweden’s peak daily death toll around mid-June, or almost the exact same time period as the Uppsala team’s adaptation.

Figure I: Imperial College Model for Sweden, March 26, 2020

Imperial College’s multi-country model used its earlier and more famous projections for the US and UK to claim validity for its more expansive set of international extrapolations. As Ferguson’s team wrote on March 26, 2020: “Our estimated impact of an unmitigated scenario in the UK and the USA for a reproduction number, R0 , of 2.4 (490,000 deaths and 2,180,000 deaths respectively) closely matches the equivalent scenarios using more sophisticated microsimulations (510,000 and 2,200,000 deaths respectively)” that they released a few weeks prior. If Imperial’s US and UK projections matched, a similar validity could be inferred for the other countries they modeled in the multi-country report.

The Imperial College team fully intended for its multi-country model to guide policy. They called on other countries to adopt lockdowns and related NPIs to reduce the projected death toll from the “unmitigated” scenario to “social distancing.” As Ferguson and his colleagues wrote at the time, “[t]o help inform country strategies in the coming weeks, we provide here summary statistics of the potential impact of mitigation and suppression strategies in all countries across the world. These illustrate the need to act early, and the impact that failure to do so is likely to have on local health systems.”

Failure to act, they continued, would lead to near-certain catastrophe. As Ferguson and his team wrote, “[t]he only approaches that can avert health system failure in the coming months are likely to be the intensive social distancing measures currently being implemented in many of the most affected countries, preferably combined with high levels of testing.” In short, the world needed to go into immediate lockdown in order to avert the catastrophes predicted by their multi-country model.

(Note: Imperial College also included a third possible mitigation scenario for stricter measures on top of general population NPIs, aimed at further isolating elderly and vulnerable people, projecting it could reduce Sweden’s numbers to between 16,192 and 33,878. They further modeled a fourth possible “suppression” scenario consisting of a severe lockdown that would reduce human contacts by 75% for the duration of the pandemic and maintain them for a year or more until population-wide vaccination was achieved. It predicted 14,518 deaths. Sweden clearly did not adopt either of these approaches).

One year later we may now look back to see how Imperial College’s international projections performed, paying closer attention to the small number of countries that bucked his lockdown recommendations. The results are not pretty for Ferguson, and point to a clear pattern of modeling that systematically exaggerated the projected death tolls of Covid-19 in the absence of lockdowns and related NPIs.

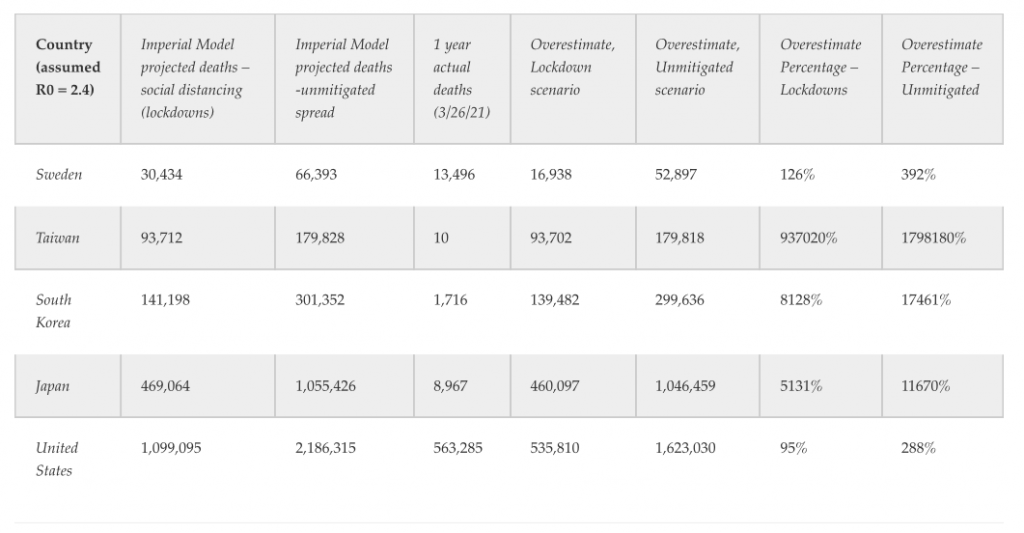

Figure II compares the Imperial College model’s projections for its “social distancing” scenario and “unmitigated” scenario against the actual outcomes at the one-year mark after its release. These projections reflect an assumed replication rate (R0) of 2.4 – the most conservative scenario they considered, meaning Imperial’s upper range of projections anticipated substantially higher death tolls. The countries examined here – Sweden, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea – are distinctive for either eschewing lockdowns and similar aggressive NPI restrictions entirely or for relying on them in a much more limited scope than Imperial College advised. The United States, where 43 of 50 states adopted lockdowns of some form, is also included for comparison.

Figure II: Performance of Imperial College Modeling in 4 Non-Lockdown Countries & the United States

As can be seen, Imperial College wildly overstated the projected deaths in each country under both its “unmitigated” scenario and its NPI-reliant “social distancing” scenario – including by orders of magnitude in several cases.

Similar exaggerations may be found in almost every other country where Imperial released projections, even as most of them opted to lock down. The Imperial team’s most conservative model predicted 332,000 deaths in France under lockdown-based “social distancing” and 621,000 with “unmitigated” spread. At the one year mark, France had incurred 94,000 deaths. Belgium was expected to incur a minimum of 46,000 fatalities under NPI mitigation, and 91,000 with uncontrolled spread. At the one year anniversary of the model, it reached 23,000 deaths – among the highest tolls in the world on a per capita basis and an example of extreme political mismanagement of the pandemic under heavy lockdown to be sure, but still only half of Imperial College’s most conservative projection for NPI mitigation.

Just over one year ago, the epidemiology modeling of Neil Ferguson and Imperial College played a preeminent role in shutting down most of the world. The exaggerated forecasts of this modeling team are now impossible to downplay or deny, and extend to almost every country on earth. Indeed, they may well constitute one of the greatest scientific failures in modern human history.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Phil Magness is a Senior Research Fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research. He is the author of numerous works on economic history, taxation, economic inequality, the history of slavery, and education policy in the United States.