Failed Imagination: The Problem with Stories From Cuba

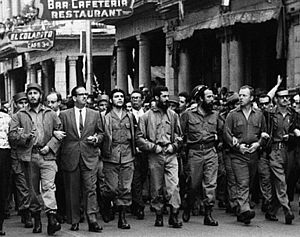

Featured image: This photo was taken on March 5, 1960, in Havana, Cuba, at a memorial service march for victims of the La Coubre explosion. On the far left of the photo is Fidel Castro, while in the center is Che Guevara, on the right: William Alexander Morgan and Eloy Gutiérrez Menoyo. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Recent accounts of Cuba are what ethicists call “bottom-up”. They draw upon what people say – in the streets, in resorts, in taxis. Such accounts claim to be objective because they start from the lives and stories of people, as described and told by them.

The claim to objectivity is naïve. The stories we hear and how we hear them depend upon values and expectations. Some values and expectations have more influence than others. The playing field for stories is not equal.

Recently, I read yet another account by a North American intellectual who traveled to Cuba for the first time. She spoke to Cubans and reported what they said: They want better cars, more freedom to choose. They’d like elections like those in the U.S. She drew conclusions, some of them insightful.

The problem is not that the views she reported are uninteresting or unworthy of respect. They are not. Rather, the problem is a complete lack of awareness of the stories that are not heard by her, because they can’t be, because they are unexpected, and because they are hard.

Cuban writer, Miguel Barnet, introducing The Biography of a Runaway Slave, writes that Estevan Montejo, whose story about escaping slavery is told in the first person, did not write an autobiography.[i] As a story about a human being, it depends on others. It is not, and can’t be, an individual story.

Montejo’s story could not be heard as the story it is, about a person, without the decades-long armed struggle that transformed racist expectations in the region.[ii] Independistas, resisting the dehumanizing ideology of imperialism, made it possible for Montejo’s story to be about someone like ourselves.

In Cuba in the 1990s, I encountered the work of award-winning Cuban writer, Marilyn Bobes.[iii] It helped me see the challenge of understanding Cuba. It was hard to understand Cuba, standing alone as it did, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, mocked by the international press, its demise expected within months.

Bobes’ “Alguien tiene que llorar” is a story about stories told by close friends of Maritza, who defied sexist, homophobic expectations in a patriarchal culture. Maritza, before she committed suicide, was an independent lesbian architect who thought love is an invention to placate the losers (women).

Maritza rejected a larger story according to which women must auction themselves off to men, concern themselves with appearances, and without children can never realize themselves. Maritza didn’t live according to that story. She rejected it, implicitly and explicitly, with her life and way of being.

Yet only one friend, Cary, understands that rejection. The others explain Maritza’s death in terms of that very same story: Maritza couldn’t realize herself because she didn’t have children and a man. The friends never knew Maritza but they don’t know that. They each explain why she died, except Cary.

Cary is closest to Maritza not because she understood more about Maritza but rather because she knew there was more to understand. And Cary knew that understanding Maritza was hard. Although Cary did not fully understand Maritza, she understood that she did not understand her.

So it is with Cuba. There’s a story about freedom and greed that Cuba has rejected for centuries. It has several names. One is liberalism. Early nineteenth century priests, wanting independence, understood how liberalism served imperialism. José Martí pursued the argument. Cuba’s struggle for independence, and the Cuban Revolution, have defied the now globalized story of philosophical liberalism.

And yet, like Maritza’s friends, who were friends, many explain Cuba in terms of the very story Cuba has defied, and replaced. They take for granted their own understanding of democracy and freedom, without argument, as if there can be no argument against such a view, and apply it in their conclusions about what’s happening in Cuba. They do it with good intentions, out of ignorance.

They miss out. Of course, it is hard to try to understand. It can be confusing, as it was for Cary. Cary accompanied Maritza to lonely stretches of beach that Maritza liked to frequent on cold, grey days. She tried to follow Maritza’s reasoning. Maritza herself has been in love, she admits to Cary, but by that point in the conversation, Cary is no longer sure what they are talking about.

Fidel Castro talked about two struggles: One is a political, social struggle for justice in Cuba, and the other is for the story to be told about that struggle. A Canadian writer told me she found that statement depressing. She is probably another intellectual taking stories at face value.

Castro’s statement describes reality: Some ideas need to be struggled for, even to be considered, like Montejo’s story as a story about a person.

In a square near the University of Havana is a large replica of Don Quixote. Some on the left say Cuba should now give up chasing windmills. Cubans should not bear the “burden” of keeping impossible dreams alive. They don’t know that “burden” is age-old.

Don Quixote’s strange mixture of “madness and intelligence” delighted some and infuriated others. Those collecting stories, unwilling to engage, or even recognize, the story that biases them, see only the “madness” part of the mixture. They don’t venture further.

If doing so is chasing windmills, it might be worthwhile. Sometimes we must believe first before we can discover. It is the way knowledge works, driven by interest, by imagination. Cary followed Maritza, and discovered that another vision was possible, even if (so far) unrealized. In the end it’s better than telling and collecting stories without admitting the story those stories unwittingly impose.

We know its disastrous results. It might be time to consider windmills.

Susan Babbitt is author of Humanism and Embodiment (Bloomsbury 2014).

Notes

[i] Barnet, Miguel, The biography of a runaway slave (Curbstone Press, 1994).

[ii] E.g. Ferrer, Ada, Insurgent Cuba: Race, nation and revolution, 1868– 1898 (University of North Carolina Press, 1999)

[iii] Bobes, Marilyn, Alguien Tiene Que Llorar (7– 24) (Havana, Cuba: Casa de las Americas, 1995). Rpt. inCubana: Contemporary fiction by Cuban women (Beacon Press).