Every St. Patrick’s Day, Everywhere, All at Once: A Disaster for Ireland

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (desktop version)

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

March 17 is traditionally St Patrick’s Day, a day when ‘Irishness’ is celebrated all over the world. This date is traditionally held to be the date of the death of St Patrick (c. 385 – c. 461), the patron saint of Ireland. It is marked by parades through the main cities and towns of Ireland, and in recent years it has become popular as a festival around the world with famous buildings being lit up green and major rivers being dyed green.

However, in recent decades the symbolism of St Patrick’s Day has changed dramatically and promotes negative stereotypes (e.g. leprechauns) of the Irish people to a world audience. This is not good for Ireland or the Irish people.

It must also be noted that St Patrick is seen as the patron saint of Ireland because he defeated pagan ideology in favour of Christianity. However, pagan ideology had a strong connection with nature and the cycles of nature that resulted in seasonal festivals such as Beltaine (1 May), Lughnasadh (1 August), Samhain (1 November) and Imbolc (1 February).

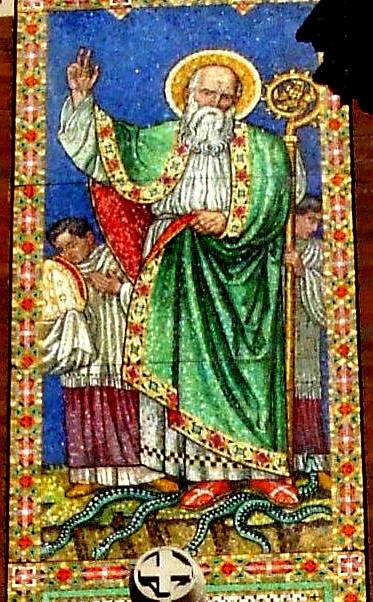

St Patrick

Not a lot is known about Saint Patrick except he is believed to have been a Romano-British Christian missionary who was kidnapped by Irish raiders and brought to Ireland as a slave. After six years as a shepherd he went home and became a priest. He then returned to Ireland to convert the pagan Irish to Christianity. He is famously believed to have driven the snakes out of Ireland despite the fact there is no record that Ireland ever had snakes.

It is more likely that the snakes refer to the pagans themselves:

“Scholars suggest the tale is allegorical. Serpents are symbols of evil in the Judeo-Christian tradition—the Bible, for example, portrays a snake as the hissing agent of Adam and Eve’s fall from grace. The animals were also linked to heathen practices—so St. Patrick’s dramatic act of snake eradication can be seen as a metaphor for his Christianizing influence.”

It is believed that he died on 17 March and was buried at Downpatrick. It is also believed that the date is suspiciously close to Ostara, a pagan holiday:

“It wasn’t arbitrary that the day honoring Saint Patrick was placed on the 17th of March. The festival was designed to coincide, and, it was hoped, to replace the Pagan holiday known as Ostara; the second spring festival which occurs each year, which celebrates the rebirth of nature, the balance of the universe when the day and night are equal in length, and which takes place at the Spring Equinox (March 22nd this year). In other words, Saint Patrick’s Day is yet another Christian replacement for a much older, ancient Pagan holiday; although generally speaking Ostara was most prominently replaced by the Christian celebration of Easter (the eggs and the bunny come from Ostara traditions, and the name “Easter” comes from the Pagan goddess Eostre).”

St Patrick’s Day Parade

As a child I remember being brought to the parade and seeing a very dignified parade of marching pipe bands and symbols of the Irish state and nation such as the Irish army. By the 1980s it had been reduced to low levels of commercialisation (such as multiple floats advertising a major security firm). Later, the influence of Macnas took over and a kind of Celtic primitivism became very influential.

St Patrick’s Day, Downpatrick, March 2011 (Licensed under Wikimedia Commons)

The commercialism of the St Patrick’s Day Parade also resulted in Irish people dressing up as red-bearded and green-hatted leprechauns:

“Films, television cartoons and advertising have popularised a specific image of leprechauns which bears little resemblance to anything found in the cycles of Irish folklore. It has been argued that the popularised image of a leprechaun is little more than a series of stereotypes based on derogatory 19th-century caricatures.”

Along with this negative stereotype came a change in terminology as St Patrick’s day became known as Paddy’s Day, a derogatory term for Irish people (Paddy). The festival has become an excuse for all-day drinking and riotous behaviour, feeding into the negative stereotypes of ‘drunken paddys’.

St. Patrick Parade, Fifth Ave., New York 1909 (Licensed under the Public Domain)

In a way the St Patrick’s Day parade of recent years does symbolise the Ireland of today just as the content of past parades represented the prevalent ideologies of their day too. The colorful, brash, internationalism of the parade now is similar to other major festivals around the world (such as Brazilian Carnival) and, similarly, has more of a feeling of public catharsis than a celebration of national identity.

The kind of drinking and self-mocking celebrated now on St Patrick’s Day has more in common with the work of the Roman satirical poet, Juvenal (c. 100 CE), who wrote that “the People have abdicated our duties [and] now restrains itself and anxiously hopes for just two things: bread and circuses.” Public palliatives for societal woes only temporarily cover up the real problems facing Irish people today as the housing, energy and financial crises deepen.

Spring is a time of rebirth and renewal. This is what is really needed now, the rebirth of the politics of social justice, and the renewal of our deep connection with nature and life – a movement away from the theology of death.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed country by country here. Caoimhghin has just published his new book – Against Romanticism: From Enlightenment to Enfrightenment and the Culture of Slavery, which looks at philosophy, politics and the history of 10 different art forms arguing that Romanticism is dominating modern culture to the detriment of Enlightenment ideals. It is available on Amazon (amazon.co.uk) and the info page is here.

He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

Featured image: Patrick banishing the snakes (Licensed under CC BY 2.5)