Eurasia: The Strategic Triangle that Is Changing the World

While the world continues to decipher, or digest, the new Trump presidency, important changes are afoot within the grand strategic triangle that lies between Russia, Iran and China.

Away from the current chaos in the United States, major developments are progressing, with Iran, Russia and China coordinating on a series of significant moves crucial for the future of the Eurasian continent. With a population of more than five billion people, constituting about two-thirds of the Earth’s population, the future of humanity passes through this immense area. Signaling a major change from a unipolar world order based on Europe and the United States to a multipolar world steered by China, Russia and Iran, these Eurasian states are carving out a leading role in the development of the vast continent. As part of the challenges faced by these leading multipolar countries, the disruptive events originating in the post-WWII Euro-Atlantic world order will need to be tackled.

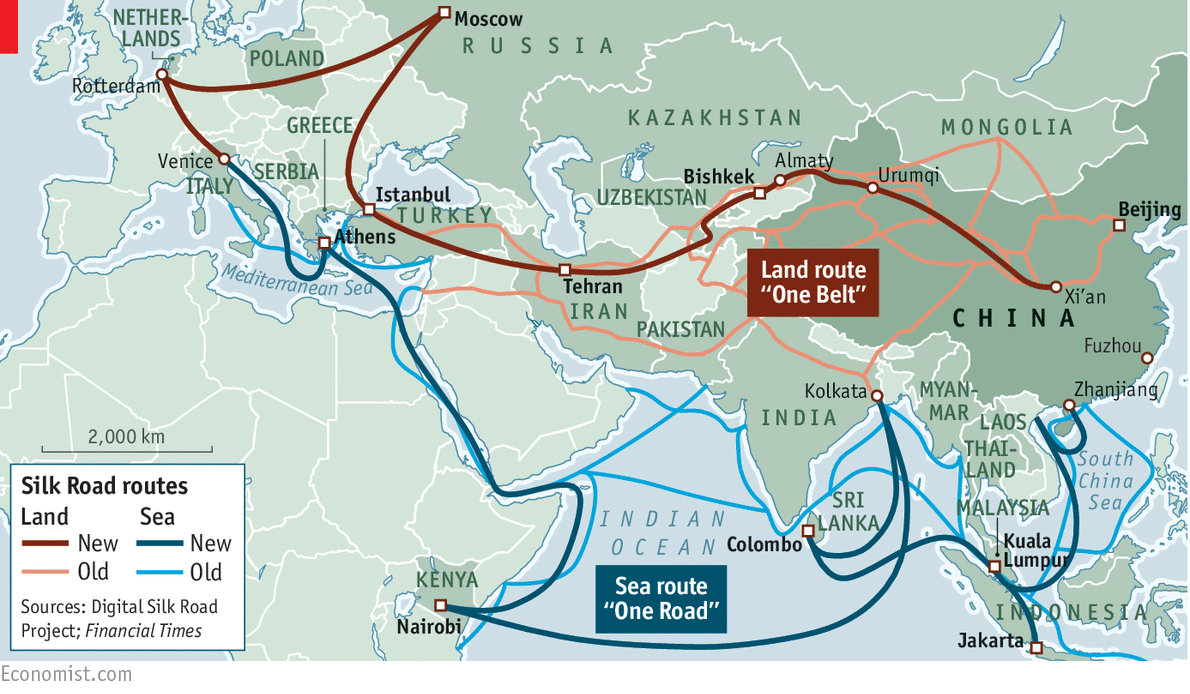

Looking at major projects within the Eurasian continent, one thing that stands out is the role of China, Russia and Iran in different areas under their influence. The One Belt, One Road project proposed by Beijing (investments of around one trillion dollars over the next ten years); the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) advanced by Moscow to integrate the former Soviet republics of Central Asia; and Iran’s role in Middle East aiming to bring stability and prosperity to the region – all are central to Eurasian development. Of course, being multipolar, all these projects fully converge, requiring concerted and joint development for the overall success of the Eurasian continent.

In this sense, the areas of greatest turmoil include areas that fall under the sphere of influence of these leading Eurasian states. The main concentrations of upheaval can be easily identified in the Middle East and North Africa, not to mention the area of the Persian Gulf, where Saudi Arabia’s criminal war against Yemen has now continued unabated for the past 24 months.

Islamic terrorism, a source for cooperation.

The common source of instability for the Eurasian continent stems from Islamic terrorism, deployed as an instrument of division and conflict. In this sense, the Saudi and Turkish role in nurturing and spreading Wahhabism as well as the Muslim Brotherhood means that they are directly opposed to the stability of the Chinese, Russian and Iranian sphere. With the full financial support of China, and military support of Russia, Tehran’s role in the region unsurprisingly becomes decisive. Iran is the country in which Sino-Russian influence is manifested at all levels in the region and beyond. The deterioration of the military situation in Syria has nevertheless obliged Moscow to intervene militarily in support of Syria, a key regional ally of Iran, but also provided a perfect way to counter Saudi-Turkish influence in the region. The growing Shia crescent linking Iran, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon is vital for retaining the influence of a multipolar world in the region. Washington has thus far been able to dictate matters through the actions of Saudi Arabia and Turkey, its regional cat’s paws, whose interests often align with that of Zionist elements, neoconservative and Wahhabi, that exist within the US deep state. Of course, Washington seeks to preserve the unipolar world order through its regional allies, aiming to remain the ultimate arbiter of Middle Eastern affairs, an area reverberating with instability from the Persian Gulf to North Africa.

It is no wonder, then, that Moscow has sought to establish a special relationship with the post-Morsi (Muslim Brotherhood) government in Egypt, which will curtail the Saudi-American influence on Cairo and North Africa, especially following the destruction of Gaddafi’s Libya. Al Sisi’s signals are encouraging, representing one of clearest examples of a multipolar world in the making. Egypt accepted Saudi funding during the time of highest tension between Doha and Riyadh, an obvious moment of weakness on the part of Cairo, especially after the coup that removed Morsi, who was supported by Qatar, Turkey and the United States. Yet in recent times, Egypt has been happy to cooperate with Moscow, especially in regard to arms. (The purchase of two Mistral ships from France assumes the further purchase of weaponry from Moscow; the same is the case with nuclear-energy development as an alternative to the massive importation of oil from Saudi Arabia, which was suspended by Riyadh following the commencement of dialogue between Cairo and Damascus). Egypt seeks a strategic positioning in the region that winks at the Russo-Sino-Iranian triangle (talks on Egypt joining the EAEU have been in the air for quite some time), although not completely ruling out the economic contribution of Saudi Arabia and the United States. On the contrary, the influence of Turkey and Iran is rejected and declared hostile, mainly because of the continuing relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood, a major concern in the Sinai.

Stability in the Middle East and North Africa relies on an expansion of Iran’s mediating role; important financial contributions from the People’s Republic of China (take a look at the situation in Libya and the reconstruction in Syria); and military cooperation with the Russian Federation. The importance of focusing on these areas of the globe can not be overstated, representing the first steps towards a more fundamental restructuring of the world order in different parts of the Eurasian landmass.

Caucasus, Central Asia and Afpak: Syria as a case study.

Often when looking at the danger posed by political Islam and Wahhabi extremism, three key areas of the Eurasian continent are usually under consideration: the former Soviet republics of Central Asia; the complicated border between Afghanistan and Pakistan; and the Caucasus area. In these areas, cooperation between China, Russia and Iran is once again playing a key role, seeing many attempts to mediate tensions and conflicts that would potentially be catastrophic for economic-development projects. The recent terrorist attacks in Pakistan in Lahore showed the true face of cooperation between Afghanistan and Pakistan, strongly encouraged by China and Russia. Shortly after a brief exchange of fire between the militaries of Afghanistan and Pakistan on their common border, an agreement was reached between Kabul and Islamabad to reduce tensions and advance the peace talks heavily sponsored by Moscow and Beijing. The need to halt the escalation of tensions between Pakistan and Afghanistan is one of the primary focuses of Russia and China in what is one of the most unstable regions of the world and what are transit lines for future projects led by the China-Iran-Russia alliance. The instability of this particular area depends largely on the role that India, Saudi Arabia, the US and Turkey intend to play to counterbalance the Eurasian trio. It is not at all coincidental that Moscow is trying in various ways to reach a complex understanding with each of these players. Saudi Arabia and Turkey are the center of control and administration for international terrorism, Riyadh and Ankara’s negative influence being felt from Syria and Libya through to Pakistan, Afghanistan and the Caucasus. The determining factor is not always the United States, though Washington naturally encourages all kinds of destructive efforts directed against the integration of the Eurasian continent.

Syria appears to be the first point of understanding reached on paper between Turkey and Russia, and could, if it obtains a positive outcome to the conflict, represent a foundation on which to build a strategic cooperation in areas like Afpak and Central Asia. In this sense, the energy-corridor incentives represented by pipelines, of which Russia is the main player, should not be underestimated, as in the case of the Turkish Stream. Also in the Caucasus, another area of extreme instability, the role played by Russia and Iran was decisive during the four days of war in Nagorno-Karabakh.

The energy factor is certainly a big incentive for Saudi Arabia, which has long observed energy diversification with interest by focusing on civilian nuclear power, something of which Russia is a world leader. Moscow plays its cards variously by providing military and economic cooperation to its closest partners (Iran, China, Syria, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan); strengthening bilateral alliances through the incentive of cooperation in weapons systems (India, Pakistan and Egypt); and energy cooperation with seemingly distant nations (UAE, Qatar, Saudi Arabia) in order to pry open a breach through which to gather broader geopolitical arrangements.

The overall strategy of the three leading Eurasian nations aims primarily to strengthen the national borders of the countries with the most turbulent regions. Putin’s recent trip to Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan aims to strengthen the soft underbelly of the Russian Federation, eliminating the threat and influence of radical Islamic terrorism in order to allow for the expansion of economic cooperation in the Eurasian Union. While not an easy task, it is certainly encouraged by the prospect of mutual gain for the nations involved, with mutually agreeable bilateral agreements in the place of diktats. In a sense, it is what the People’s Republic is attempting to establish in Central Asia, one of the most volatile regions of the world, endeavoring to reach agreements and expand its pool of energy resources as occurred recently in Turkmenistan. Another example of the reduction of threats to the Eurasian landmass can be seen in the Xinjiang province, which China has focused on as an area that needs an easing of socio-political tensions, in the interests of obviating outside efforts to destabilize China, directed mainly from Turkey through its partner Turkmenistan.

The Indian role in this context is more difficult to understand, compressed within an anti-Pakistan and anti-Chinese sentiment, as well as a subjection to the United States, together with good historical friendship with the Russian Federation. The role of New Delhi in this part of the world is the most indecipherable, seeing India’s (inscrutable) efforts to advance its own strategic goals. The strategic importance of Moscow and Tehran are essential in balancing the Indian position. Historically India was an important ally of the USSR, and India militarily continues to advance important military projects with the Russian Federation. In recent years, the Islamic Republic of Iran has greatly contributed to the Indian diversification of energy supplies. The fact that Tehran is a privileged partner of Beijing shows what a multipolar world looks like, and also helps to balance the anti-Chinese sentiment deeply rooted in the Indian establishment. In this case, Russia and Iran are clearly playing a mediating role between China and India. The fact that India and China are both important gas customers of Iran, as well as the fact that both China and India are cooperating with Russia on a military base, helps understand how Moscow and Tehran are cutting out Washington and diluting the anti-Chinese sentiment in India.

The tensions that Washington fans in India is increasingly being doused, not least because it is at odds with India’s need to create a stable business environment for development without precluding any opportunity for partnership. The most difficult challenge is the peace process between Afghanistan and Pakistan, which goes against Indian geopolitical interests that are aligned with the American position in the region. To mitigate this situation, strong joint cooperation is required. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) will try to implement a framework within which to discuss and reach all-inclusive agreements between the parties involved. Once again, a regional discussion between Eurasian powers does not include the old world order of the US and Europe.

The role played by China and Russia in Central Asia can not be overstated, because of the importance of the potentially available energy resources. This is not to mention the future cooperation between the two gigantic economic areas, such as with the European Union and Asia, that will transit through Central Asia, transforming the Eurasian Union into a golden bridge linking Europe and Asia. At the moment, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) is an organization like the SCO that tends to prioritize the fight against terrorism; but increasingly it is seen as offering a place for discussion, an organization that offers a path toward economic cooperation by first laying down the necessary foundation of territorial stability. In this area of the globe, economic prosperity depends heavily on social, political and military stability.

After all, this is the great challenge that Russia, China and Iran are facing, namely to de-escalate the hot zones (Middle East, Persian Gulf and North Africa) by eradicating the terrorist problem, and preventing the escalation of tensions in neighboring regions lying immediately within their sphere of influence (the Caucasus, Afghanistan-Pakistan and Central Asia), thus avoiding destructive destabilization.

It is only once an international framework is in place that these areas will see the stability that will allow for the deep and wide-ranging economic cooperation that will be of historic significance. In this sense the entry of India and Pakistan into the SCO was the first step of a complicated deal led by China and Russia that covers a dozen nations. The same situation can be observed with the future entry of Iran into the SCO, with the specific objective of expanding the influence of the SCO in unstable areas like the Persian Gulf and Middle East. In this sense the discussions regarding the entry of Egypt into the SCO as a full member is aimed at expanding the SCO’s positive influence even as far away as North Africa.

Russia, China and Iran are laying down the foundations for developments that will make the US irrelevant in its struggle to extend its unipolar moment. Combining the population of the Eurasian continent with the demographic and economic growth of these areas, it is not too difficult to understand how, in the space of just over two decades, the area stretching from Portugal to China, which includes dozens of nations of all latitudes and longitudes that extend from the Arctic regions of the Russian Federation to the Indian sea or the Persian Gulf, will be the central pivot around which the global economy will revolve. The combination of land and sea trade corridors will make the Eurasian continent the world’s core, not only in terms of production but also in terms of trade and consumption, due to the increase of wealth of the middle-class areas of the world.

In a strategic vision that historically incorporates decades of planning, Tehran, Moscow and Beijing have fully understood that stability is the primary objective to be achieved in order to effectively promote economic development that benefits all the nations involved. In Asia, ASEAN has begun to have a less belligerent attitude towards China, although Beijing continues to ensure its strategic interests with the construction and militarization of artificial islands in the South China Sea. The Philippines’ president, Rodrigo Duterte, seems to understand the potential gains of multipolar cooperation, and the path followed by his country in recent months forges a path for all other Asian nations, especially following the abandonment of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) project by Washington. It remains to be seen what role the old European continent can play while still being shackled to the American strategy that is focused on isolating Russia, China and Iran, committed to advancing Washington’s global hegemony at cost, even if it involves committing economic suicide, as can be seen in Ukraine with the sanctions against the Russian Federation.

One should not rule out a future change in direction in Europe as a direct result of failed policies that for too long have genuflected before American interests at the expense of the interests of European citizens. It is not accidental that many parties considered populist and nationalist have every intention of turning to the East and pursuing cooperation that for too long has been denied by the stupidity of Western elites.

China, Russia and Iran appear to have every intention of accelerating the project of global cooperation and show no intention of shutting the doors to new players from outside Eurasia, especially in an increasingly globalized and interconnected world. Just take a look at the links of the People’s Republic of China with the development projects in South America to understand how the scope of these projects aim to include all nations without exception. This is the foundation on which the new multipolar world order is based, and sooner or later the American and European elites will understand this. The dilemma for Western elites lies in their diminished role in the future international order: no longer will the US and Europe be the lone protagonists but actors who are part of an international cast. The unipolar international order is running out of time and the old world order is in crisis. Will Europeans and Americans be able to accept a role as co-protagonists, or will they reject inevitable historical change, condemning themselves in the process to oblivion?