The End of the “Greater Middle East Project”: The Case of Kurdistan

Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential elections has had dire implications for the American “Greater Middle East” project which has guided US foreign policy in the Middle East since it was first put forward in 2003. Trump’s reorientation toward internal US problems (migration, economy, protectionism), the emergence of new geopolitical rivals (China and Iran) and the turning point being reached in the war against Daesh in Syria have resulted, more or less, in a new balance of powers in the Middle East. While the situation is still rather chaotic, one fact is certainly clear: the Americans have lost their dominant position.

On top of all of this, following the events of July 2016, Turkey, one of the central players in the Middle East, headed for geopolitical rapprochement with Russia and began to distance itself from the United States. Turkish authorities accused Washington of having played a role in the attempted coup, driving a wedge in the relationship of the long-time allies. Up to this point, Turkey, together with Israel, were seen as outposts for pushing US foreign policy interests in the Middle East. However, contradictions began to emerge over the US’ reliance on the Kurdish separatists, who are locked in a state of open conflict with the Turkish government. As a result of disagreements over this issue, America began to lose one of its most important regional partners. After the coup attempt, hostilities between Turkey and the West escalated even further: Turkey openly discussed the possibility of a withdrawal from NATO, the West countered by threatening Turkey’s ongoing EU integration process.

Unsuccessful negotiations between Washington and Ankara over the extradition of accused coup leader Fethullah Gulen only complicated matters further, as did disputes over Turkey’s detention of Pastor Andrew Branson. The contradictions eventually reached their sharpest point as the US attempted to dissuade, and ultimately, threaten Turkey over their purchase of Russian S-400 missile defense systems.

In parallel with these processes, Saudi Arabia and Qatar began to adjust their foreign policy accordingly. Realizing that the West could no longer fully control the situation in the region, Qatar began to seek support from Russia, which had successfully shown the strength of its influence in Syria.

Qatar, being a traditional ally of Turkey (predominantly via the Muslim Brotherhood), began to follow Turkey’s lead, even improving relations with Iran. Saudi Arabia, a regional adversary of Qatar, was forced to follow a similar strategy… of course, not in terms of improving relations with Iran (their main regional adversary) but by establishing ties with Russia. This is evidenced in Riyadh’s attempt to buy S-400s from Moscow against Washington’s wishes.

Thus, the United States has lost most of its regional partners, with only the invariable Israel remaining a part of the Greater Middle East project. Trump has bent over backward to keep this relationship secure, even if it means finally destroy Washington’s relations with the Islamic world altogether and instead rely on the Kurds… a plan as obvious as it is failed.

Revising the Greater Middle East Strategy

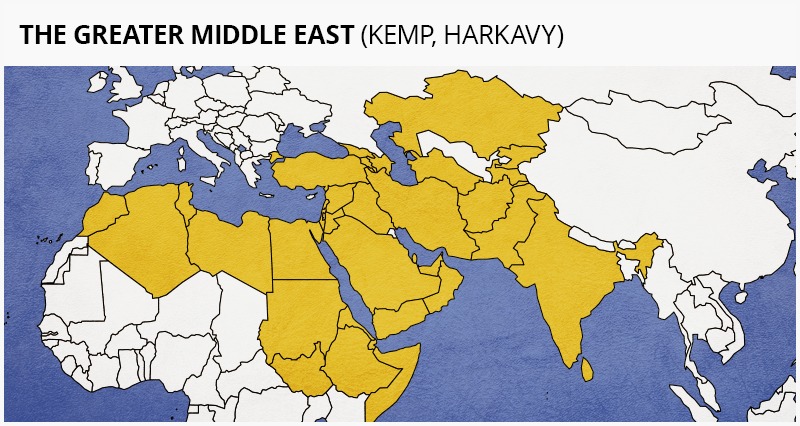

The Greater Middle East project was the guiding light of US foreign policy strategy in countries like Afghanistan, Pakistan and Central Asia for decades. As of 2011, the project grew to include the Arab nations of North Africa and Syria in particular. On a project map designed by J. Kemp and R. Harkavy, the Republic of Turkey and Kazakhstan were also included.

The project aimed to spread and deepen “democracy” in the region. The plan had two sides: the official one, which was supposed to contribute to a rise in power for states led by pro-Western reformers (initially completely unrealistic) and the unofficial one, which was to actively destabilize existing Islamic regimes, support color revolutions, riots and even bring about regime change.

Creating controlled chaos has always been a central goal of the project. This goal was realized in Libya and Iraq, but its implementation in Syria was disrupted by the effective policy of Russia and Syria’s alliance with Iran and Turkey. In addition to these major powers, Hezbollah played a critical role in disrupting Washington’s plans.

However, the plan also involved the creation of a wider arc of instability – from Lebanon and Palestine to Syria, Iraq, the Persian Gulf and Iran – right up to the Afghanistan border, where NATO garrisons are located. The levers of the project were numerous: large-scale financial investments in the economies of the Middle Eastern countries, support for extremist groups, information warfare, alongside open provocations and false-flags operations. During the implementation of the project, many Middle Eastern countries underwent “color revolutions” backed by Western operators who induced controlled chaos and exploited social media networks in order to use various countries’ social, political, religious, ethnic and economic problems against them. During the “Arab Spring”, this strategy led to regime change in 3 states: Tunisia, Egypt and Libya, while Libya and Syria were left in a state of civil war.

The US and EU were never completely unified over the project. At one G8 summit, the Greater Middle East project was criticized by French President Jacques Chirac, arguing that Middle Eastern countries do not need this kind of forcibly exported “democracy.”

The strategy for “spreading democracy” in the region had essentially become thinly , if at all, veiled US intervention in the domestic political life of Middle Eastern states. Military assaults began in Afghanistan, Iraq, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Sudan and Syria. However, the results were less than favorable for most, resulting in floods of refugees, including representatives of terrorist organizations. Western Europe was forced to face the brunt of the backlash for Bush and Obama’s Middle Eastern adventures. The globalists and neoconservatives were united in their efforts, and although their destructive goals were achieved, the majority of Americans did not even understand why these costly and brutal operations were being prioritized.

Trump properly grasped the mood of voters and promised to curtail the Greater Middle East project. After coming to power, he at least began to move in that direction: in December 2018, he decided to withdraw all American troops from Syria.

Project Implementation Opportunities

After the wave of color revolutions and the Arab spring, some states in the Middle East realized the real threat posed by America’s evolving strategy. Before their eyes, centralized and well-ordered states were turning into ruins. It was not just a change of leadership: the very existence of entire countries was threatened. Hence, many leaders concluded the need for a new emphasis on sovereignty. For example, Turkey, an important player in the region, focused on geopolitical interaction with Russia and China, reorienting itself toward the Eurasian axis which caused a crisis in relations with the United States (the purchase of the S-400s from Russia led the United States to refuse to sell Turkey F-35 fighter jets as previously agreed).

The region around Syria was gradually cleared of extremist groups, with the remaining militants relegated to the province of Idlib and the south-east of the country. When Imran Khan became Prime Minister, Pakistan also moved further away from the United States and began to develop pro-Chinese policies while establishing strategic relations with Russia.

Looking at all of these factors, we can conclude that the Greater Middle East project has already been curtailed.

However, the American strategy only partly depends on who runs the White House. That’s why it’s important to understand the role of the so-called Deep State in US politics. The Deep State has its own logic and direction, something which Trump needs to take into account. Due to the Deep State’s influence, America continues to take advantage of a number of complex problems for the region, one critical example being its tactic of fomenting conflict through support for the forces fighting for an independent Kurdistan. This conflict in particular is shaping up to be the “last battle” of the Greater Middle East project.

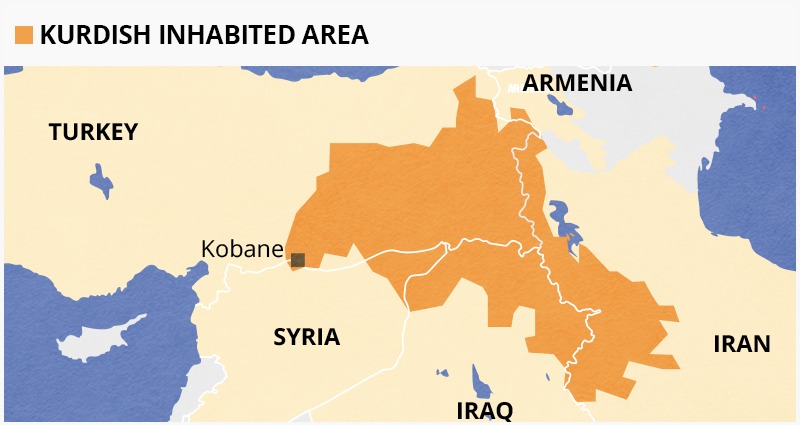

The Kurdish Map

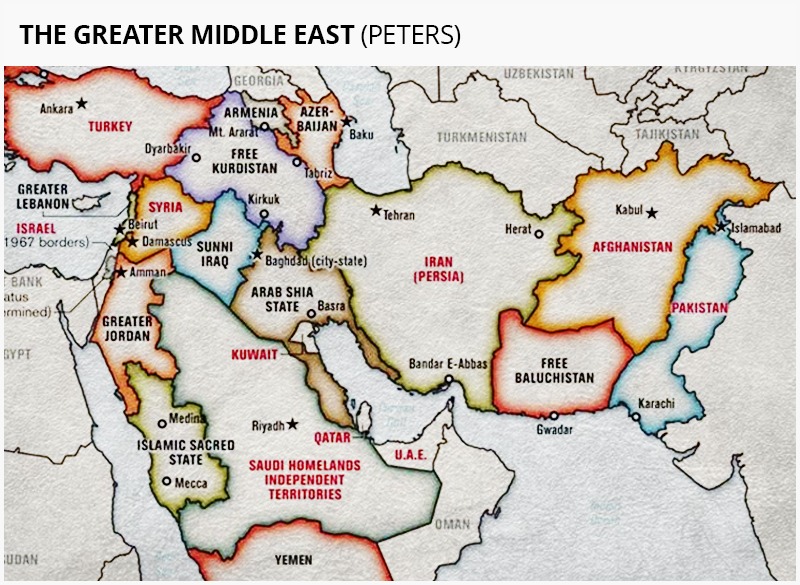

The Greater Middle East project, according to Ralph Peters and Bernard-Henri Levy (the plan’s most important European propagandists), involves the creation of an independent “Free Kurdistan” which includes a number of territories in Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria. The creation of a single state entity through the unification of the 40 million Kurds residing in these countries could lead to a number of serious problems.

The idea of creating an independent Kurdish state openly and clearly began to emerge at the end of the 19th century (the first Kurdish newspaper in Kurdish began to circulate in Cairo in 1898). At the end of the 19th century, the Kurdish people seemed as though they might actually embrace Turkey. The founder and first president of the Republic of Turkey, Kemal Atatürk, was positively greeted among the Kurds – some Alevite groups interpreted the role of Atatürk as Mahdi, the last successor of the prophet Muhammad. However, after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Kurds did not receive their desired autonomy, which began to cause problems.

Historically, the “Kurdish map” has always been an ace-up-the-sleeve of various geopolitical powers striving for influence in the Middle East: Woodrow Wilson first supported the creation of an independent Kurdish state after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the US again supporting Kurdish forces in the 1970s in an attempt to overthrow the Iraqi Ba’ath party… in 2003, it used the Kurds to overthrow Saddam Hussein. The Iranians used the Kurds against Iraq in the 70s as well, while in more recent times the Syrians have tried to use the Kurdish issue against Turkey. Israel has strongly supported the Kurdistan project in order to weaken the Arabic States.

The fragmentation of the Kurds who live in Iraq, Iran, Syria, Turkey, as well as in the Caucasus, is one of the reasons why it is currently impossible to build a single Kurdish state. The Kurdish people have historically been prone to clan and political fragmentation. There are several factors which strongly separate the various groupings of Kurds.

One complication to the formation of an independent Kurdistan is linguistic fragmentation – Soran is spoken in eastern Iraq and Iran, while Kurmanji is spoken by Syrian, Iraqi and Turkish Kurds. Some Kurds in Iraq speak yet another dialect – Zaza.

Religious issues also hinder the unification of Kurdish tribes and clans into a single state: the majority of Kurds are Sunnis (with a large number of Sufi tariqas), while Zoroastrian styled Yazidism is less widespread. Meanwhile, In Iran, Kurds are mainly followers of Shia Islam. Yazidism is considered the Kurdish national religion, but it is too different from orthodox Islam and even from the rather syncretic Sufi Tariqas.

Yazidism is prevalent mainly among the northern Kurds – Kurmanji.

New year celebrations in Lalish, 18 April 2017. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Religion is a mixture of Zoroastrianism (manifested in the doctrine of the seven Archangels and a special attitude to fire and the sun, along with a strong caste system) with the Sufi teachings of Sheikh Abi ibn Musafir. The unexplored and closed sources of the Yazidi religion strongly complicate the Kurdish factor. The Muslim nations surrounding them often characterize the Yazidi Kurds as worshipers of Shaitan. Shiite-style Kurds (mainly residing in Iran) are a separate group, difficult to reduce to the Shiite branch of Islam as such, and are more approximately a Zoroastrian interpretation of it. Interestingly, Shiite Kurds believe that the Mahdi should appear among the Kurds, suggesting a degree of ethnocentrism.

Another important factor in assessing the chances of creating an independent Kurdistan is their cultural specificity in the Iranian context: the Kurds, unlike other Iranian peoples, maintained a nomadic lifestyle far longer than others.

We can conclude that building a unified Kurdistan is essentially a utopian idea: the rich diversity of the religious, linguistic and cultural codes would be impossible obstacles in building a traditional nation-state… and this is without taking into account the stiff opposition to the project from other states in the region, including Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria. For these countries, the implementation of the Greater Kurdistan project would actually mean the end of territorial integrity and a fundamental weakening of their sovereignty, and perhaps even their complete collapse (particularly given the fact that other ethnic minorities would likely want to follow the Kurdish path).

Although an independent state might be a pipe-dream, Turkey’s current tactical ally, Russia, could play a positive role in solving and regulating the Kurdish issue by other means. Being neutral in the conflict, despite historically positive relations with the Kurds, Russia could act as a mediator and guarantor of Kurdish rights while fighting to maintain the territorial integrity of existing states. Russia could assist in providing the Kurds with the possibility of cultural unification, protection and the development of their identity, but this implies the concept of a cultural and historical association rather than a political one. This association could grant the Kurds a certain degree of autonomy while preserving the territorial borders of the states in which they live.

In Iraq, a solution to the Kurdish issue is possible through the construction of a tripartite confederation between the Shiite majority, the Sunnis (with the rejection of Salafism and extremism and with the Sufis playing a predominant roe) and the Kurds (mainly Sunnis). It is also necessary to take into account Assyrian Christians, Yezidis and other ethnic-religious minorities of Iraq.

At present, Iraqi Kurds have the maximum autonomy and prerequisites for the implementation of the Kurdistan project under the leadership of Masoud Barzani. The origins of the relative independence of Iraqi Kurdistan are in American operations during the 2000s. It was during this period that Iraqi Kurds gained a maximum degree of autonomy. At the moment, Iraqi Kurdistan has its own armed forces, currency and even its own diplomats. Its main income comes from oil sales. Interestingly, the per capita GDP in Iraqi Kurdistan is quite high and exceeds that of Iran and Syria.

Moreover, in September 2017, the autonomous region’s leadership held a vote on secession from Iraq – 92.73% voters voted in favor of creating an independent Iraqi Kurdistan. Erbil’s plans in this direction have been met with negativity both in Iraq and in Turkey (despite Erdogan’s partnership with Barzani).

However, the situation in Iraq has its own difficulties and complications – the Barzani clan controls only half of the region, the second part of Iraqi Kurdistan, including the capital located in Sulaymaniyah, is controlled by the Talabani clan (the “Patriotic Union of Kurdistan” party is subordinate to it). Conditional partnerships have been established between the Barzani clan and the Talabani clan, but their orientations differ due to their diverging political priorities: this also manifests itself in terms of foreign policy: The Talabani clan is focused on Iran while the Barzani clan is focused on Turkey. This situation shows that even in the strongest part of Kurdistan there are heavy internal contradictions which make state-hood impossible.

In Turkey, the project faces several particularly sharp problems, a notable one being the ruling circle’s strong views on the Kurdish issue. Erdogan came to power in part by playing on the Kurdish factor (in efforts such as the Western-supported Kurdish–Turkish peace process), but, as relations with the West worsened, he began to return to a national Kemalist course, which traditionally takes a tough anti-separatist position, seeing any compromises with separatists as weakening Turkey’s national unity. As a result, Erdogan is now pursuing a policy of suppressing the movement for Kurdish autonomy – the PKK has responded in turn by carrying out terrorist attacks and issuing ultimatums.

The most stable situation for the Kurds in the Middle East is the one in Iran. The Kurds there live in four provinces – Kurdistan, Kermanshah, Western Azerbaijan and Ilam.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The second seed of the Kurdish state is a network of associations of followers of the partisan leader Abdullah Ocalan, a left-wing politician, and the mastermind/creator of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party. Ocalan’s teachings are about creating a special political union of Kurds in the spirit of “democratic confederalism”. This project promotes the creation of a virtual Kurdish state, based on socialist ideas. The center of this teaching is currently Syrian Kurdistan (Rojava), which has raised strong concerns from Turkey who sees the Syrian Kurds as an integral part of the PKK. Consequently, Erdogan’s policy is based on the uncompromising political rejection of the Syrian Kurds political formations, which is why he is preparing for military operations in northeastern Syria.

In Ocalan’s ideas, we find the interesting postmodern political project of creating a post-national virtual state called a “confederation” which relies on disparate associations, clans and tribes rather than a formal nation. This network-based society surprisingly coincides in its general features with postmodern theories in international relations, promoting the end of the era of nation-states and the need for a transition to a virtual structure of power. In philosophical terms, the idea is inspired by left-wing French postmodernists, in particular, the Deleuzian concept of the “rhizome” – a scattered mushroom in which there is no center, but everything is still connected in a network. The idea is manifested in the Kurdish anarcho-communist project which combines leftist ideas, postmodern philosophy and feminism. Representatives of anarchist communities inspired by globalist financier George Soros also have sympathy for the idea of a virtual rhizomatic state.

The main enemies of Ocalan’s project are Turkey and Syria (in Syria, the followers of Ocalan are based in the North – they call themselves the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria). Support for the Syrian Kurds has also come from the US government… for several years, they have sent financial assistance to the Kurds to fight Daesh terrorists. In the Western media, far more attention was paid to the Kurd’s fight against Daesh than the actual large-scale victories of the Syrian and Turkish armies.

Israel is betting heavily on the Kurds in its regional policy since the Israelis are well aware that a Kurdish state would be a fundamental problem for all of their regional opponents (Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria). Although the Kurds are Muslims, and therefore hardly enthusiastic about Israeli policy toward Palestine, the pragmatic interests of Kurdish nationalism often outweigh confessional solidarity.

Following the recent strengthening of Assad’s position in Syria, Iran’s tough opposition to US policy and Turkey’s geopolitical reversal toward multipolarity, America is also increasingly putting its money on the Kurds, literally and figuratively. In 2019, the Ministry of Defense allocated $300 million to support Kurdish forces in the war against Daesh. The United States, according to UWI sources, continues to supply arms to Kurdish militants from the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) today, using them as a weapon in the struggle to overthrow Assad. A report by the Carnegie Foundation notes that Kurdish groups in Syria and Iraq that successfully conducted operations against Daesh are “key US allies.” In the Western media, the Kurds are usually portrayed as “peacekeepers.”

The Americans (who are well aware of the difficulties involved) believe that the process of trying to build a Kurdish state will weaken or destroy their Middle Eastern rivals. After all, the creation of a free Kurdistan would entail the territorial division of Syria, Iran, Iraq and Turkey, creating a wide-ranging but controlled chaos.

An Alternative to the Greater Middle East Project

It has become apparent that the Kurdish issue needs to be resolved in the framework of a new project, an alternative to the globalist’s Greater Middle East strategy. It is important to create an alternative project that could rely on Ankara, while taking into account the interests of Baghdad, Tehran and Damascus. It should be Moscow, and not Washington (at least, not the American deep state) that plays the central mediating role. The project should work to preserve the territorial integrity of existing nations and even strengthen their overall sovereignty… at the same time, it is extremely important to take into account the diversity of peoples in the Middle East, and the Kurds in particular. Within this new political framework, the Kurds should have certain powers and guarantees – but at the same time, they must not be allowed to be exploited by globalist forces looking to destabilize the region to their own advantage.

In the context of the transformation of the Middle East, powers should reorient themselves towards cooperation with the Eurasian pole. China and Russia could become the key players in resolving the Kurdish issue, ensuring a balance between real Kurdish interests and the countries seeking to maintain their territorial integrity. The only way out of the current Kurdish impasse is finding a strict, consistent and integrated approach to solving the problem of Kurdish identity.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

All images in this article are from UWI unless otherwise stated